Last October, Marilyn Begay was walking along a street in Farmington, New Mexico, when two men jumped out of a van and approached her. They claimed to work at the nearby San Juan Regional Medical Center, and offered her a ride. Begay, a 46-year-old Navajo woman who had struggled with alcohol use and was under the influence at the time, says she agreed to get in the car after she recognized two passengers, friends of her brother. But once inside, she was plied with alcohol to the point of blacking out, and driven close to 400 miles southwest, across state lines, to a residential home in Phoenix.

After she refused to provide her name, birth date, and Social Security number to a man at the home, she says, “they locked me in a room and told me they’d take me home in the morning, but I noticed an unlatched window and escaped through it.” She slept at a bus stop that night, and the next day called relatives in Farmington. The cousin who picked her up, Reva Stewart, was no stranger to these bizarre and frightening scenarios.

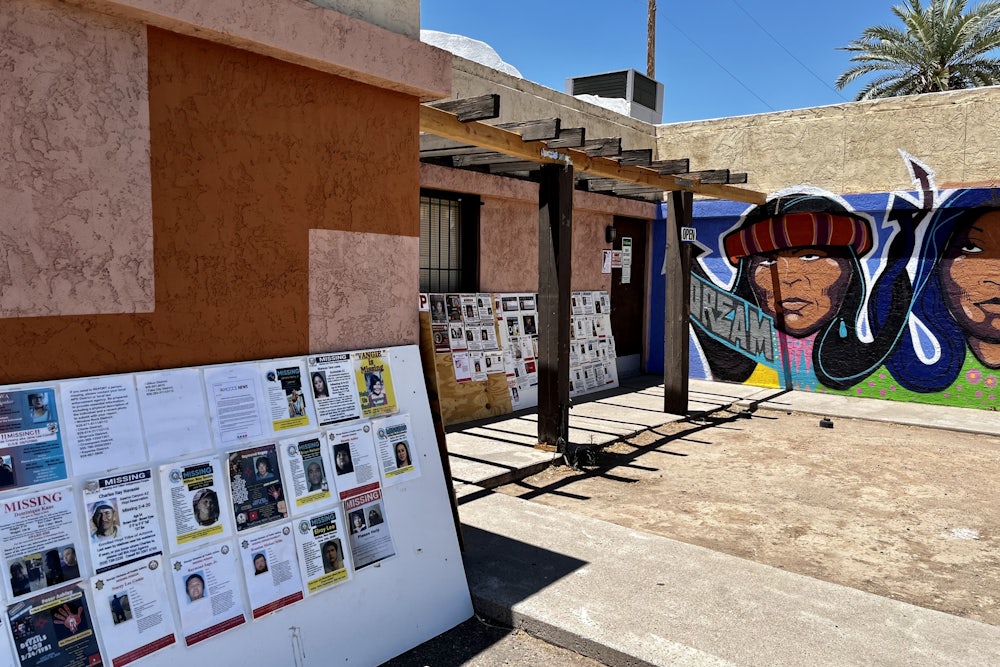

For years, Stewart had posted notices of missing Indigenous people—mostly women—on bulletin boards outside her shop in Phoenix, Drumbeat Indian Arts. Last summer, Stewart started receiving more notices for men and also began observing strange activity outside her store, located across from the Phoenix Indian Medical Center. “These white vans would stop at the bus stops, then two men would appear and talk to our Native relatives,” said Stewart, who is Navajo and 54 years old. “They drove back and forth all afternoon.” Most who were solicited would wave the men off, but some would get into the van.

In the months after retrieving Begay, Stewart would receive dozens of calls that detailed horrific abuses of Native people who were picked up off the street and brought to nondescript locations. There was the 70-year-old man who was admitted to the intensive care unit after suffering severe injuries while trying to escape a home; the mother who called about her son who’d endured an unsupervised dry detox and ended up on life support; the relative who claimed that a five-person family, including a 4-month-old child, had been recruited by scammers to live in a home.

These were not random incidents. They were all connected to an elaborate, ongoing, multistate criminal scheme to defraud Medicaid of hundreds of millions of dollars by targeting Native communities’ most vulnerable people—some of whom have paid with their lives.

For decades, coverage for treatment of substance use disorder wasn’t standardized. If you could afford it, you could pay out of pocket for care. If you lived in an area with publicly funded treatment, you might have access to community-based resources like 12-step programs. Starting in the 1970s, recovery housing, such as sober homes, grew to fill the need for stable, long-term living environments.

Despite its proven benefits, recovery housing hasn’t been formally connected to any of the health care or social services systems. To date, most states don’t regulate the category. “Anybody can open up a house and throw four or five people in it, charge them, and say, ‘We have a sober house,’” said Joe Pritchard, CEO of Pinnacle Treatment Centers, which runs 162 clinical facilities and sober homes nationwide, though not in Arizona. A similar lack of regulation has applied to treatment centers that provide clinical services, where medications like naltrexone are administered alongside other therapies.

Federal changes to coverage broke the industry wide open. It started with the passage of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act in 2008, which mandated insurers provide coverage for substance use disorder treatment on par with that for other medical conditions. Then, two years later, the Affordable Care Act authorized plans on its exchanges to cover treatment for the disorder. An additional 62 million people became insured, and the numbers of those seeking treatment skyrocketed.

Although the two laws led to better outcomes for both patients and insurers, they also created new opportunities for fraud. Because recovery-living facilities, such as sober homes, are considered housing and are usually peer-run, they can’t bill private insurance and don’t have access to public funds like Medicaid (rent and other living costs are often split among housemates). But licensed treatment facilities can, and so sober homes looking to exploit the system either work in tandem with—or are themselves operated by—these facilities. In a scheme known as patient brokering, sober-home operators and recruiters get kickbacks, usually in the form of cash payments, for delivering “patients” to treatment centers, which then illegally bill those individuals and their insurance for services they don’t provide.

“The fraud is actually pretty simple,” said Dave Sheridan, executive director of the National Alliance for Recovery Residences. “You charge a lot of money for things like outpatient services and laboratory drug testing, and you use some of the proceeds from that to pay for housing.”

On the streets of Arizona and New Mexico, as far as South Dakota, and directly on tribal lands, recruiters for these outfits have coerced people apparently struggling with homelessness, behavioral health issues, or substance use disorder to residential homes, short-term rentals, or motels in the Phoenix area. Victims have reported being offered limitless alcohol but only two bottles of water a day, given blue pills they believe were sedatives, or forced into dry detoxes that have led to delayed hospitalization and death. Many of these locations are reportedly unsanitary and crowded, and run by largely absent staff who have refused to contact people’s families, return their personal items, or let them leave.

The scammers bill Arizona’s American Indian Health Program—a plan under the state’s Medicaid agency, the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, or AHCCCS—for care that isn’t administered. Victims who aren’t already enrolled are either made to enroll or have their information used without their knowledge. “Anyone can call ACHHHS and register for the plan. You don’t even have to show a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood,” Coleen Chatter, a former case manager for Navajo Nation’s Regional Behavioral Health Authority, told me. Often, scammers have moved people from home to home in order to bill them repeatedly. In one case, according to Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes, AHCCCS had been billed for more than 13 hours a day of alcohol rehabilitation services—for a patient who was 4 years old.

Government officials have known about such fraud for many years—and sometimes taken action. In 2018, the Arizona legislature passed a series of bills aimed at prohibiting patient brokering and creating more oversight on sober homes statewide, including a licensure requirement through the Arizona Department of Health Services. But Democratic Governor Katie Hobbs, who took office in January, alleged in a May press conference that her Republican predecessor, Doug Ducey, enforced the law “on a case by case basis, never implementing the systemic overhauls necessary to weed out this problem and failing to deliver true accountability.”

On the federal level, in 2016, Senators Elizabeth Warren, Marco Rubio, and Orrin Hatch called on the Government Accountability Office to review federal and state oversight of sober homes. The GAO evaluated five states, finding that four of them—Florida, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Utah—had conducted investigations into potentially fraudulent sober homes. “Activities identified by state investigators included schemes in which recovery home operators recruited individuals with substance use disorder to specific recovery homes and treatment providers, and then billed those individuals’ insurance for extensive and unnecessary drug testing for the purposes of profit,” its report read.

While the scams cited by the GAO largely defrauded private insurers, Arizona’s scheme is unusual in that it has targeted Medicaid funds. “I don’t think it’s too much to say this is one of the biggest scandals in the history of Arizona when it comes to our government,” Mayes said in May, announcing a long-overdue crackdown that has only just begun.

In January, after months of advocacy led by the Arizona state Senator Theresa Hatathlie, who is Navajo, and other tribal leaders, the FBI launched an investigation into the scams. In a call for victim information, the agency noted that scammers “frequent community gathering locations such as flea markets, trading posts, and medical centers to pick up clients,” some of whom “are intoxicated or offered alcohol during transport.” It added, “When the individuals regain a functional state in Phoenix (or other locations), they have no idea where they are or how they got there.” Navajo Nation leaders estimate that as many as 7,000 people have been victims of the scheme.

On May 16, the state announced a crackdown on the scam. Mayes said that health care payouts for outpatient behavioral health services—the category these entities fall under—went from $53 million in 2019 to $668 million in 2022. The amount that went to fraudulent actors is currently under investigation, but Mayes believes the majority of it occurred through the American Indian Health Program and amounts to hundreds of millions of dollars. “It could go well beyond that,” she added.

Arizona’s AHCCCS system also suspended or terminated payments to more than 150 treatment centers tied to the scheme, which officials said originated with a Nevada-based criminal syndicate. Arizona punishes patient brokering with civil penalties of at least $25,000 and up to $250,000. So far, Arizona officials have indicted 45 people and recovered $75 million. But some say tougher laws are needed. “Civil penalties don’t work. These homes have fines built into their business models,” said Alan Johnson, the chief assistant state attorney for Florida, which has combated similar schemes for decades. Since making patient brokering a criminal offense, Florida has had more than 120 prosecutions. After the first five prosecutions, Johnson told me, “there was a palpable difference. People closed up shop. They knew we were coming.”

Arizona is contending with another crisis: As these fraudulent homes close, hundreds of people are becoming displaced, with nowhere to go, as temperatures in Phoenix reach life-threatening levels. Officials have promoted a 211 hotline to connect people with temporary housing, transportation, and vetted treatment centers. But callers have reported experiencing long wait times and are sometimes directed to homeless shelters instead of health care facilities. There’s also concern that the hotline is itself difficult to access. “How are people who are now on the streets going to know about these resources? How is someone who’s in a home without a phone going to call 211?” said Raquel Moody, a 36-year-old who is Hopi and White Mountain Apache. “We need to think about this through the people. We need to go get them.”

Moody understands their needs more than most. Last year, after she was released from a court-mandated halfway house following three years in prison, she had a plan: Four years sober, she would become a peer-support specialist, someone with lived experience who guides others in addiction recovery. But when she returned home to the White Mountain Apache Reservation to help take care of her younger sister, Moody relapsed. She, along with a cousin, Carlo Jake Walker, checked into a sober home called Open Hand, on the outskirts of Phoenix. “I knew I needed to get back if I was going to stay on the right path,” she told me.

But Open Hand was nothing like the first halfway house she’d experienced. Its manager was absent, and there was more alcohol than food and water. (Owner Blad Herrera declined to comment.) When Moody discovered that Walker had started drinking there, they got into a fight. The next morning, December 10, Walker left the home before Moody woke up; she left the following day. When her cousin didn’t resurface, she distributed posters and looked for him in other sober homes.

Since leaving Open Hand, Moody has stayed in at least seven homes, simultaneously searching for Walker while seeking out a safe recovery space for herself. Each home would claim legitimacy, but soon enough, she would discover that it openly allowed drinking and drug use. “Every time I discovered people drinking or not being cared for, I’d speak up and they’d kick me out,” Moody told me. One day, she got a call from an unknown number; the man on the line had a proposition for her. “He told me he’d pay for my gas, my food, all my expenses, if I bring my people to him,” Moody said. She was offered $500 per person. When she confronted him—“Are you just buying us now?”—he blocked her.

On May 6, barely a week before Arizona announced its crackdown on sober home scams, she saw her cousin’s name in The Arizona Republic. It was an obituary. Walker, who was 38, had died two days after leaving Open Hand. He had been cremated, a process that goes against White Mountain Apache tradition, and buried at White Tanks Cemetery, a resting place for unclaimed remains. A PVC pipe, stuck in orange dirt, marks the site.

“If this happened to my brother, how many of our people are out there just buried with no names?” said Moody. All Walker had wanted was sobriety, she added. “And these places, they all say they’ll help, but in the end, it’s just money that they see in us.”

Open Hand is still accepting clients.