Remember when self-driving cars were supposed to eliminate drivers and start whisking us anywhere we wanted with a simple hail from our smartphones? Or how about when Hyperloop pods in vacuum tubes were going to shoot us between cities around the world at unimaginably high speeds and low cost? Those are just a few of the big transport visions that, just a few years ago, Silicon Valley told us were right around the corner. Unfortunately, they’ve never really arrived.

Today, there are some driverless cars roaming the streets of a few cities around the country, but, at least in San Francisco, they’re getting plenty of bad reviews. Vehicles from companies like Waymo and Cruise have a reputation for blocking traffic and getting in the way of emergency vehicles, to the point that local officials want them out of the city altogether. Meanwhile, Elon Musk’s Boring Company, which was spun off from SpaceX in 2018, made some big promises of its own, but has thus far built little more than an amusement ride in Las Vegas. Uber scrapped its plans for networks of flying cars, and startups devoted to the Hyperloop, a proposed method of high-speed intercity transport, are dropping dead as higher interest rates choke off their access to capital—investors know they’ll never deliver.

Tech billionaires don’t have a great track record when it comes to fixing our transportation system—but we keep giving them second chances. For 15 years, we’ve waited for Silicon Valley to solve the problems on our roads, and it’s continually failed to deliver. Instead, tech companies have kept us trapped in our cars by distracting us from investments in improved transit and other transport options. Now, we’re letting them load our vehicles with new technologies so they can get their own cut of the profits made from our dependence on automobiles—by scraping our data, forcing subscriptions into our cars, and using drivers as guinea pigs to test new tech.

Through the 2010s, the cultural excitement around big technofixes for the future of transportation, like Uber and Hyperloop, was almost palpable. Tech journalist Kara Swisher appeared in a 2014 video for Waymo’s self-driving prototype, calling it “an obvious idea” that showed “where things are going.” In Chicago, Mayor Rahm Emanuel contracted Elon Musk’s Boring Company in 2018 to build a speedy transport system between the airport and downtown that he claimed would ensure it “will take longer to get through security at O’Hare than to get to O’Hare.” (It was never built.)

Not only were new ideas about how we could get around coming from the tech industry, whose well-resourced marketing departments were great at getting the public to believe they were making the world a better place, but the American transportation system had a myriad of problems. These issues have only gotten worse in the years we’ve been waiting for tech’s magical solutions.

Transportation is the biggest source of emissions in the United States, but its challenges go much deeper than its carbon footprint. More than two-thirds of Americans drive to work, and commuting times continued to get longer through the past decade: nearly 10 percent of people spent more than an hour on their commutes in 2019. In 2022, even as many people were still working from home, it was estimated that Americans waste an average of 51 hours a year stuck in traffic.

The soaring cost of living has also sent the average annual cost of car ownership above $10,000, making it an even bigger drain on people’s already stretched budgets. Cars have also been getting deadlier. Last year, an estimated 42,795 people were killed on U.S. roads, and pedestrian deaths have reached a 40-year high. That’s not to mention all the other health hazards that come from spending all that time behind the wheel.

People are frustrated with the state of transportation—they have every right to be. It makes sense that our society was willing to put its faith in the Elon Musks of the world to fix how we get around. But for all its big ideas, the tech industry did more to distract us from real solutions than deliver the solutions to those worsening problems.

In 2018, the New York Times reported on how the Koch brothers were using the prospect of driverless cars as part of their war against public transit. The libertarian billionaires and longtime fossil fuel allies were funding Americans for Prosperity to organize dozens of campaigns in cities and states around the country to stop measures that would put more money into transit service. One of their primary arguments was that public transit was outdated and a waste of money because self-driving cars were just a few years away. Five years later, we’re still waiting for the self-driving revolution—but the Koch brothers’ bad-faith ideas about public transportation are still around.

During the mid-2010s, Elon Musk’s Boring Company went around the country selling cities on its car tunnels as solutions to their transportation woes, but rarely delivered any tangible product. Take Fort Lauderdale: The city needed a new train tunnel and went to the Boring Company. But once a deal was signed in 2021, the Boring Company instead sold the city not on building a train, but rather on building a tunnel for Teslas to the beach. As of earlier this year, nothing had been built, and local media was reporting that the deal could be dead.

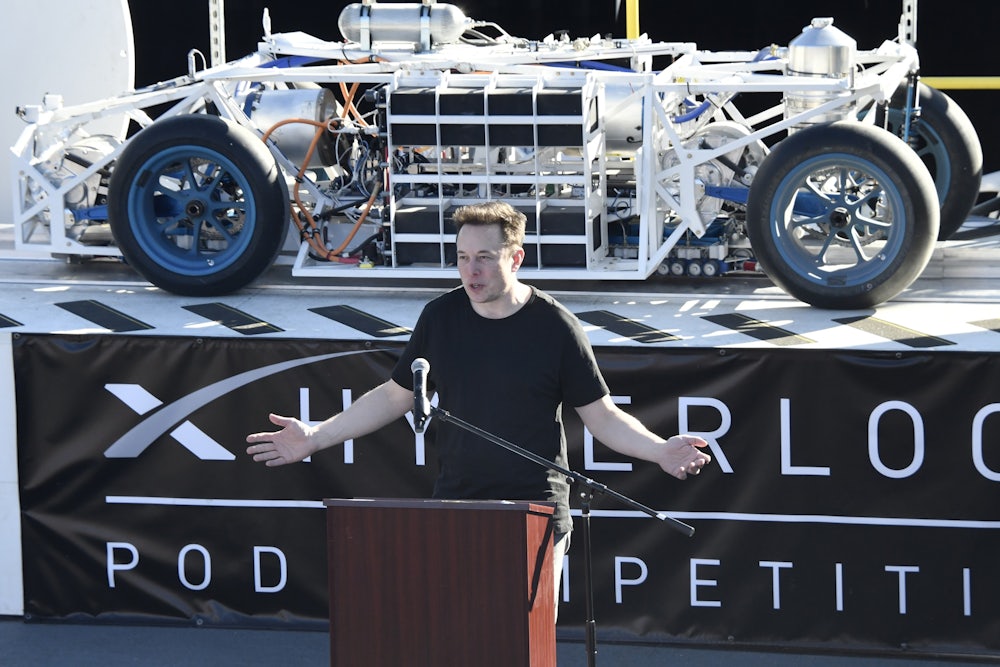

The most egregious false solution may be the Hyperloop. The modern version of the concept was proposed by Musk a decade ago as a pure hypothetical. Musk, a noted public transit hater, saw it as a way to reduce support for California’s planned high-speed rail line between Los Angeles and San Francisco. “It seemed that Musk had dished out the Hyperloop proposal just to make the public and legislators rethink the high-speed train,” reporter Ashlee Vance wrote in his 2015 biography of Musk. “He didn’t actually intend to build the thing.” Musk’s ultimate hope? “High-speed rail would be canceled,” explained Vance.

That didn’t stop governments from the Midwest to Dubai and even India from clamoring for their own versions of the Hyperloop, and for startups to raise millions of dollars to test the technology. A decade after Musk’s initial proposal, no high-speed Hyperloops open to the public exist, and many of those companies have folded or downsized.

That’s not to say the tech industry has accomplished nothing in the realm of transportation during the last decade. While many of these companies’ big ideas have largely been abandoned and the problems in the system have become more dire, new technologies are being integrated—just not in the ways the industry promised.

For decades, the vehicles we drive have been slowly expanding in size; large trucks and SUVs now dominate the roads. This change was in part thanks to automakers, who pushed for bigger models that were more profitable for them, and warped fuel economy standards also helped incentivize the shift. This has had a serious environmental impact: The growing global demand for SUVs was the second-biggest driver of rising emissions from 2010 to 2018.

Even as we transition to electric vehicles, that pressure to go bigger hasn’t subsided. While the Toyota Prius was once the picture of a sustainable car, Tesla sidelined it by showing an electric car could be fast and powerful with a huge battery. Now automakers are following suit with large electric trucks and SUVs, while cutting production on smaller—and more affordable and efficient—E.V. models. They’re also ensuring those vehicles are packed full of digital technologies—just like a Tesla.

If you look inside many of those newer vehicles—both E.V. and gas-powered—you’ll find a massive touchscreen in the dash; in some cases, physical buttons and dials will be gone altogether with all the features crammed onto the screen. Those infotainment systems, often powered by Apple’s CarPlay or Android Auto, were promised to make driving safer by getting us to look at our phones less. But a growing number of studies are finding they’re actually making us more distracted.

Those systems are also always connected. Increasingly, data from our vehicles is constantly shared with a whole range of companies to fuel new data-driven revenue streams. Automakers are at the front of the line, but behind them are the tech companies that power infotainment systems, along with insurance companies, navigation services, and companies that pull together all that data. Those vehicle data hubs, as they’re called, make the automotive data from different providers legible so it can then be sold to other companies.

All that vehicle data comes with its own privacy concerns. The Driver Privacy Act of 2015 only covers data on a car’s Event Data Recorder—not everything else they’re generating. There has been some effort to get a congressional caucus together to examine the issue, but it hasn’t gotten far, nor has the alternative of passing a comprehensive federal data privacy bill. The European Union is actively examining in-car data and plans to craft rules to cover it, but lawmakers there haven’t gotten far, either—and as the law tries to catch up, automakers are continuing to put even more new tech into our vehicles.

The internet connectivity required for data collection in a car also enables another business model: subscription services. Automakers are now expecting drivers to shell out monthly or yearly for car features instead of just choosing what they want when they buy it. This is not isolated to just one or two companies, but all the major players. BMW is charging to enable heated seats, Mercedes is doing the same with faster acceleration, Tesla charges for additional connectivity features, and GM has big plans to expand its subscription offerings—and the revenues it derives from them—in the coming years.

The other piece of this picture is assisted driving. While self-driving cars never truly arrived, there are new systems in modern vehicles, like lane-keeping assists and adaptive cruise control, that help drivers to ostensibly make the roads safer. But as they’ve been rolled out, road deaths have continued to soar. Now, transport safety agencies are starting to more deeply investigate the impacts of these new features. A lot of that focus has been on Tesla’s Autopilot system, but the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has begun requiring crash data from any automaker using assisted or autonomous driving technologies.

Many of the billionaires pushing grand transport visions have fallen from grace in the years since they rose to prominence. Elon Musk seems to finally be suffering the same fate after his botched takeover of Twitter revealed him as the snake-oil salesman he’s always been. It should also serve as a wake-up call that self-driving cars and Hyperloops will never improve how we get around—or at least not on any timeline that matters.

To address the problems in the system—emissions, road deaths, traffic, and all the rest of it—we need a deeper rethink not just of the technologies we use, but the type of mobility we prioritize. The problems we face come from how we’ve built cities and neighborhoods that force us to drive virtually everywhere. Fixing it requires us to challenge that through investments in better rail infrastructure, transit systems, cycling networks, and major changes to how we build communities.

Ultimately, those are political issues, not technological ones, and that means the tech industry can never effectively solve them. If we want better mobility and an improved quality of life, that’s the real path to achieving it.