The most striking portion of the Supreme Court’s student loan relief decision isn’t the decision itself, as significant as it is. The justices on Friday blocked President Joe Biden’s order to forgive billions of dollars of student loan debt in Biden v. Nebraska, ruling that he had violated federal law by trying to wipe away up to $20,000 in debt for each of millions of borrowers last year. As many as 40 million Americans will lose out on student debt relief as a result.

Nor is it the majority’s questionable analysis of standing that let it hand down the ruling in the first place. The lawsuit, filed by a coalition of Republican-led states, hinged on whether they could act on behalf of MOHELA, a federal student loan servicer created by the Missouri legislature. MOHELA has an independent legal personality and chose to not challenge the executive order on its own. That’s OK, the court said—Missouri and other states can just do it on their behalf.

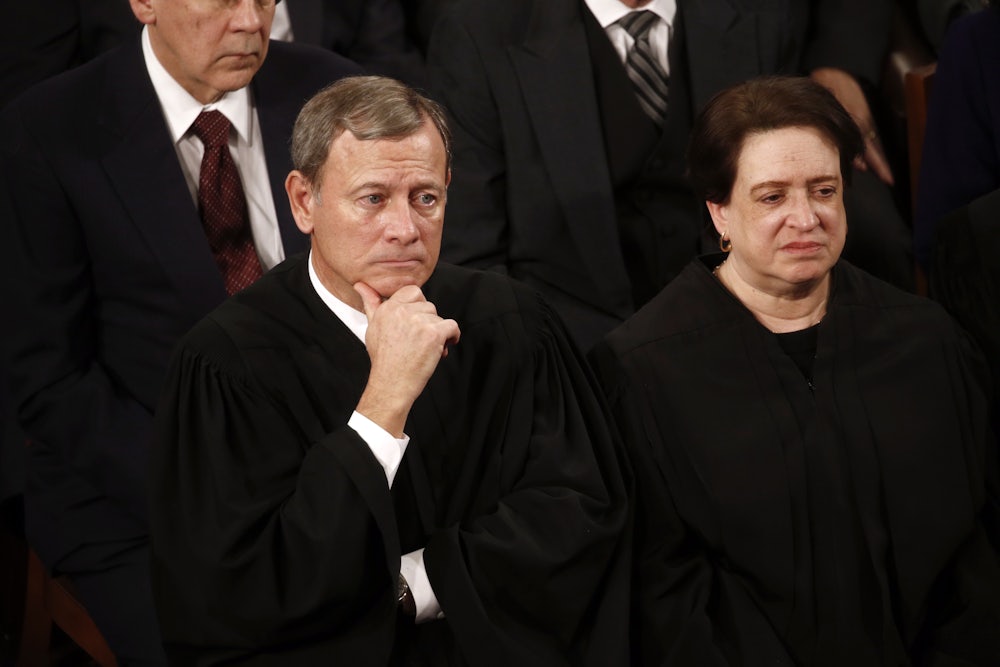

What really stands out is the final paragraph of Chief Justice John Roberts’s majority opinion. Ever the institutionalist, he takes issue with criticism of the court by some of its own members who fault it for overstepping its powers. “It has become a disturbing feature of some recent opinions to criticize the decisions with which they disagree as going beyond the proper role of the judiciary,” Roberts laments. He argues that they reached Friday’s ruling based on normal judicial methods of statutory interpretation.

“Reasonable minds may disagree with our analysis—in fact, at least three do,” the chief justice concludes, referring to the court’s three liberal members who dissented from Friday’s ruling. “We do not mistake this plainly heartfelt disagreement for disparagement. It is important that the public not be misled either. Any such misperception would be harmful to this institution and our country.”

Nobody likes to be criticized. As someone who also has to write things that the public reads—albeit to a much smaller audience and with much lower stakes—I can sympathize with that sentiment. At the same time, it is hard to square Roberts’s plea to not claim the court is exceeding its authority at the conclusion of an opinion in which it does just that.

Roberts, writing for the court, rules that the federal law which the Biden administration invoked to forgive large amounts of student debt did not authorize it. “The Secretary asserts that the HEROES Act grants him the authority to cancel $430 billion of student loan principal,” he writes. “It does not. We hold today that the Act allows the Secretary to ‘waive or modify’ existing statutory or regulatory provisions applicable to financial assistance programs under the Education Act, not to rewrite that statute from the ground up.”

The 6–3 ruling fell along the court’s usual ideological divide. In dissent, Justice Elena Kagan writes that “in every respect, the court today exceeds its proper, limited role in our Nation’s governance.” She castigates the majority for concluding that Missouri and a coalition of other Republican-led states had the legal standing necessary to challenge the order.

“[The court] declines to respect Congress’s decision to give broad emergency powers to the secretary,” Kagan wrote. “It strikes down his lawful use of that authority to provide student-loan assistance. It does not let the political system, with its mechanisms of accountability, operate as normal. It makes itself the decision-maker on, of all things, federal student-loan policy. And then, perchance, it wonders why it has only compounded the ‘sharp debates’ in the country?”

Biden’s order sought to erase up to $10,000 of student loan debt for borrowers who made less than $125,000 a year. Borrowers who also obtained Pell grants could receive up to $20,000 in relief. The Biden administration estimated that the order would erase as much as $400 billion in student loan debt and that it would affect as many as 40 million Americans.

For legal authority, the White House cited the Heroes Act of 2003, a law drafted by Congress during the early stages of the Iraq War that replaced a temporary version enacted after the September 11 attacks. It allows the Department of Education to “waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision” involving federal student loan programs. While the law was originally meant to help Iraq War veterans avoid student loan repayment issues during the war, Congress phrased it to apply to national emergencies in general.

To that end, when the Covid-19 pandemic first struck the United States in 2020, then–Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos invoked the Heroes Act to suspend student debt payments and the accrual of interest. The move was part of a raft of policy maneuvers that Congress and the Trump administration engaged in after the American economy partially collapsed that spring. The Biden administration continued the debt-repayment pause and, last year, added on additional forms of relief by wiping away a certain amount of debt for each borrower.

Republicans strongly opposed that level of relief when it was announced. At the time, however, even they acknowledged that it would be extremely difficult to challenge in court. To bring a lawsuit, a would-be plaintiff would have to show that they were injured in some way by the executive order. Without an injury, there’s nothing for the court to fix, and if there’s nothing for the court to fix, there’s no reason for it to hear the case. The Constitution only allows the courts to hear “cases and controversies,” not issue freewheeling advisory opinions.

Who is possibly injured by having $10,000 in debt removed from your student loans? Certainly not the individual borrowers who received that relief, despite some tortured attempts to claim otherwise. In a separate ruling on Friday, the justices unanimously rejected a too-clever-by-half lawsuit by two individual borrowers who were recruited by right-wing legal activists. The borrowers claimed that the order was invalid for procedural reasons and that, if it were redone properly, they might receive even more debt relief. Justice Samuel Alito, writing for all nine justices in Dept. of Education v. Brown, rejected that argument out of hand.

In Biden v. Nebraska, a coalition of Republican-led state attorneys general sought to overturn the order. How could states possibly have standing, you might ask? They do not go to college, after all. The residents of a state may go to college, but the state couldn’t sue on their behalf because they don’t have standing either. And while every state operates its own colleges and universities, those schools get the tuition payments no matter what happens to the student debt that follows, so there’s no injury—and thus no standing—to be found there.

The Republican attorneys general clung to MOHELA as their vehicle to stop the Biden administration. Missouri’s legislature created the Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority in the 1980s to act as a servicer for federal student loans. MOHELA has its own independent legal personality, meaning it can file lawsuits and defend itself from litigation on its own. MOHELA has filed no such lawsuit to challenge the debt-relief order, nor does it appear interested in filing one, even though it purportedly stood to lose out on an estimated $44 million in fees if the order went into effect.

Not to worry, the Supreme Court said on Friday. Since the order would affect MOHELA’s revenues, and thus potentially make it harder to “help” Missouri students “access student loans,” as Roberts puts it, Missouri naturally has a legal interest in the welfare of one of its “instrumentalities.” Kagan sharply disagrees with how the court misread its own precedents on the matter, as well as its ultimate conclusion.

For starters, Kagan notes, not even Missouri has claimed that anything affecting MOHELA will necessarily hurt Missouri borrowers, and it probably couldn’t claim that because MOHELA doesn’t actually issue student loans. “MOHELA is not a lender; it services loans others have made,” she points out. And even if that weren’t true, she notes, it is a canonical rule of standing that states can never sue the federal government based on alleged harms to the state’s residents.

“Missouri needs to show that the harm to MOHELA produces harm to the State itself,” Kagan explained. “And because, as explained above, MOHELA was set up (as corporations typically are) to insulate its creator from such derivative harm, Missouri is incapable of making that showing. The separateness, both financial and legal, between MOHELA and Missouri makes MOHELA alone the proper party.” She also pointedly noted that Roberts himself had previously opposed broad versions of state standing.

“If MOHELA had brought this suit, we would have had to resolve it, however hot or divisive. But Missouri?” Kagan concludes. “In adjudicating Missouri’s claim, the majority reaches out to decide a matter it has no business deciding. It blows through a constitutional guardrail intended to keep courts acting like courts.”

On the merits, Roberts and Kagan also duel over how to read language that the secretary could “waive or modify” student loan provisions. Roberts, writing for the court, rules that the Biden administration could not “rewrite that statute from the ground up.” His view that it was a radical shift from the text suffuses the opinion. “What the Secretary has actually done is draft a new section of the Education Act from scratch by ‘waiving’ provisions root and branch and then filling the empty space with radically new text,” Roberts wrote, referring to the requirement that the administration report on any changes to Congress.

Kagan, by comparison, concludes that Congress gave broad authority to the executive branch to rewrite student loan provisions during a national emergency, and the executive branch used that broad authority to do it. “How does the majority avoid this conclusion?” she asks, rhetorically. “By picking the statute apart, and addressing each segment of Congress’s authorization as if it had nothing to do with the others.” Roberts’s interpretation, she noted, makes the Heroes Act useless for future national emergencies because the court has rejected what it described as any “novel and fundamentally different loan forgiveness program.”

Perhaps the area where Kagan expresses the most frustration is on the court’s invocation of the major questions doctrine, a newfangled legal doctrine where the court claims it can block executive branch actions if it thinks Congress did not speak “clearly enough” on a matter of “vast economic and political significance.” Kagan and the doctrine’s many other critics see it as a vehicle for the court to ignore broadly written statutes and substitute its own policy preferences for those of the elected branches of government.

“Congress may have wanted the secretary to have wide discretion during emergencies to offer relief to student-loan borrowers,” she writes. “Congress in fact drafted a statute saying as much. And the secretary acted under that statute in a way that subjects the president he serves to political accountability—the judgment of voters. But none of that is enough. This Court objects to Congress’s permitting the Secretary (and other agency officials) to answer so-called major questions.”

At least two justices in the majority gave reason to believe that their concerns with student debt relief were not strictly about its legality. Justice Neil Gorsuch, who joined Roberts’s opinion, appeared to take issue with relief on policy grounds during the Nebraska oral arguments. “What I think [the states] argue that is missing is costs to other persons in terms of fairness, for example, people who have paid their loans, people who don’t plan their lives around not seeking loans, and people who are not eligible for loans in the first place, and that a half a trillion dollars is being diverted to one group of favored persons over others,” he told Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar.

So did Roberts himself. “Since we’re dealing in a case with individual borrowers or would-be borrowers, I think it appropriate to consider some of the fairness arguments,” he said in an exchange with Prelogar during the Brown oral arguments. He hypothesized about a person declining to take student loans to attend college in favor of taking out loans to start a lawn-care service. A person who goes to college, Roberts noted, will likely have a higher lifetime income than a person who does not.

“Nobody’s telling the person who is trying to set up the lawn service business that he doesn’t have to pay his loan,” the chief justice then claimed during oral arguments. “He still does, even though his tax dollars are going to support the forgiveness of the loan for the college graduate, who’s now going to make a lot more than him over the course of his lifetime.”

“I may have views on the fairness of that and mine don’t count,” he continued. “We like to usually leave situations of that sort, when you’re talking about spending the government’s money, which is the taxpayers’ money, to the people in charge of the money, which is Congress.” Everything is going fine. At this point, Roberts and the dissenters are still on the same page about the proper role of the judiciary in a democratic society.

Then things fall apart. “Now why isn’t that a factor that should enter into our consideration under the major-questions doctrine again, where we look at things a little more strictly than we might otherwise when we’re talking about statutory grants of authority, to make sure that this is something that Congress would have contemplated?” Roberts asked.

I could write at length on a weekly basis about how the “major questions doctrine” and its vague terminology gives judges room to nix the policy judgments of Congress and the executive branch in favor of their own. What is a question of “vast political and economic significance” and what isn’t? How “clearly” does Congress need to “speak” to pass the court’s muster? Fortunately, Roberts has done that better than I ever could. You could see the wheels turn in that monologue where he acknowledged that this “fairness” question is properly answered by the elected branches, not by him. And then he finds a skeleton key that lets him answer it anyway.

Roberts, for his part, notes in Friday’s opinion that Kagan didn’t really challenge the application of that doctrine in this case. “Aside from reiterating its interpretation of the statute, the dissent offers little to rebut our conclusion that ‘indicators from our previous major-questions cases are present’ here,” he complained, quoting from a concurring opinion by Justice Amy Coney Barrett that discussed the doctrine in greater detail. Kagan likely did not feel the need to rebut the particulars of the doctrine because it is, in her view, “made up.” Roberts might as well ask why Buzz Aldrin doesn’t engage with people who think the Moon landing was faked.

That brings us back to Roberts’s initial note of concern: that people might be disparaging the court by saying it was overreaching itself. “At the behest of a party that has suffered no injury, the majority decides a contested public policy issue properly belonging to the politically accountable branches and the people they represent,” Kagan replies. “In saying so, and saying so strongly, I do not at all ‘disparage’ those who disagree. The majority is right to make that point, as well as to say that ‘reasonable minds’ are found on both sides of this case. And there is surely nothing personal in the dispute here.”

Despite that olive branch, she does not relent in her criticism of the majority’s approach and notes that expressing it is essential to her duty as a justice on the court. “But justices throughout history have raised the alarm when the Court has overreached—when it has exceeded its proper, limited role in our Nation’s governance,” she writes, repeating her opening line. “It would have been ‘disturbing,’ and indeed damaging, if they had not. The same is true in our own day.”

To borrow a phrase from Roberts, the best way to stop criticism that the court is “going beyond the proper role of the judiciary” is for the court to stop going beyond the proper role of the judiciary. The conservative majority went out of its way, both on standing and on reading the Heroes Act, to find a way to kill Biden’s student debt relief order. It did so while some of the justices, including the opinion’s author, expressed deep misgivings with it on purely policy grounds. If the public might naturally conclude that the court is not really acting like a court in this case, that is not the public’s or the dissenters’ fault, but the court’s own.