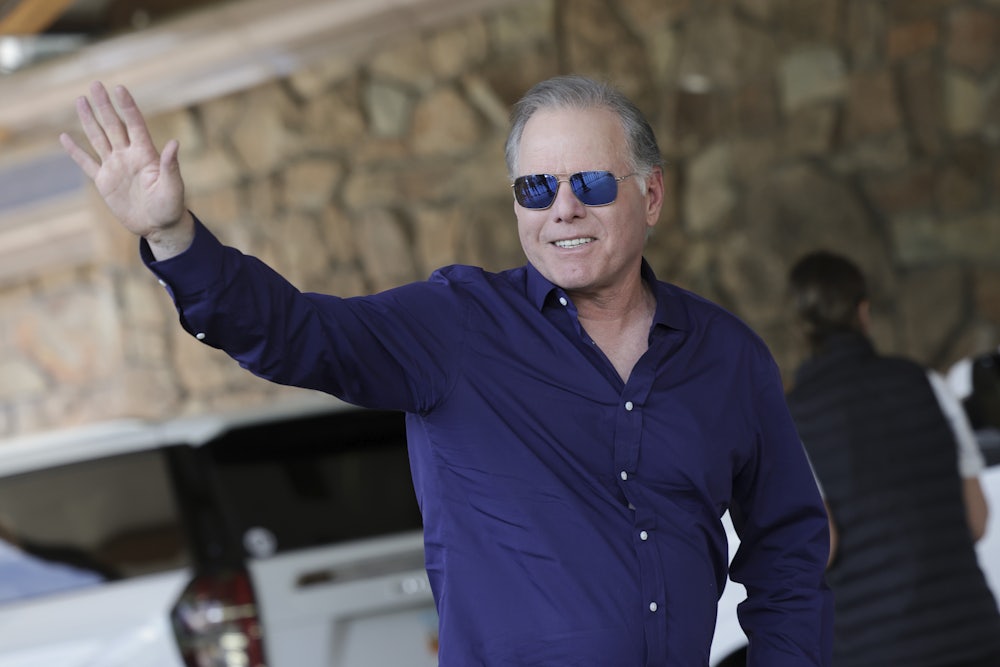

Late last month, Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav headed to Cannes for a coronation. It was a strange time for a victory lap. Zaslav had spent most of the previous year taking heavy criticism for the way he was running the company, slashing budgets and jobs, shrinking streaming libraries, and even shelving nearly finished movies so they could be used as tax write-offs. His efforts to make CNN more appealing to conservative voters had bombed spectacularly, cratering the network’s ratings and damaging its credibility with voters of all stripes.

Days earlier, Boston University students had humiliated Zaslav during a commencement address, drowning out his speech by chanting, “Pay your writers!”—a show of solidarity with the Writers Guild of America, which has been striking for weeks and drawing attention to the abysmal treatment of writers working for streaming platforms in particular. Speaking of streaming platforms, Zaslav had just overseen the launch of another new one, sort of: “Max,” a rebranded HBOMax, now with more garbage TV—and none of that baggy, prestigious “HBO” name. It got worse: A disastrous decision to change the way credits worked caused Hollywood’s three biggest unions—the WGA, the Directors Guild of America, and the Producers Guild of America—to unite in opposition. Everyone hated David Zaslav.

And yet, in France he was feted. At a party thrown by Graydon Carter, he schmoozed with Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Scarlett Johansson. The New York Times’ Michael Grynbaum described Zaslav as “the happiest man in the world” and the party as the unofficial “A-listification of Hollywood’s newest mogul.” David Zaslav had made his name producing cheap, disposable reality TV. Now he was, at long last, taking his place as Jack Warner’s successor: He had finally arrived. It was—or at least it was supposed to be—a legitimating moment.

A month later, it looks like even more of a farce than it was at the time. Zaslav is once again Hollywood’s biggest pariah, this time for gutting Turner Classic Movies, a crucial cultural space and one of the most important drivers of film preservation over the last 30 years. TCM is not, however, going to rake in cash, even though it’s not unprofitable—and so, to Zaslav, it has to be destroyed.

The problems started on Tuesday, when it was reported that WarnerDiscovery had laid off TCM’s leadership team, many of whom had been at the network for years, including its heads of studio production, programming, and marketing. TCM general manager Pola Chagnon also departed, after more than two decades with the network. One industry insider described the team to Vulture as “the people who’ve been the architect of the brand for decades.” Moreover, they weren’t being replaced—and TCM was not going to be led by someone with a history in film preservation. Instead, Michael Ouweleen, who currently leads Cartoon Network and had previously overseen TCM, would be at the helm.

The outcry was swift and furious. Spielberg and Scorsese teamed up with Paul Thomas Anderson to try to save the network. “Turner Classic Movies has always been more than just a channel,” they wrote in a statement that also suggested they were “encouraged by discussions” they had had about the network’s future with Zaslav. “It is truly a precious resource of cinema, open 24 hours a day seven days a week,” they wrote. “And while it has never been a financial juggernaut, it has always been a profitable endeavor since its inception.”

Since that inception in 1994, Turner Classic Movies has played a vital role in preserving film history and presenting it to new audiences. It is not a place that produces the new, shiny intellectual property that Zaslav and his fellow streaming CEOs covet. But it is a place of curation that is devoted to preserving films from Hollywood’s history—films that might otherwise be lost to history. “Turner Classic Movies is an important and fundamental part of people’s film understanding,” Screen Slate founder and editor-in-chief Jon Dieringer told The New Republic. “It feels too good to be true—it should be nationalized. It’s amazing that we have this commercial-free cable channel that has shown incredible films, many of which haven’t been available on disc or streaming.”

“It is really the only consistent place where an entire art form exists,” archivist and filmmaker Gina Telaroli told The New Republic. Although some limited archives exist, like the Library of Congress, studios themselves have largely been responsible for preserving their own movies, a process that has resulted in countless films, particularly from early Hollywood, being lost. “The first chunk of cinema is a vastly different art form than what’s being made today,” Telaroli continued. “To do away with that is just a huge atrocity. No other art form has to deal with that. You’d never be like, ‘Here are the three pieces of classical music.’ That’s not how that exists! Or, ‘Here are the three paintings, enjoy them!’ That’s what it feels like with film—we have Casablanca and two other films. That’s all there can be.”

TCM has been a place that has preserved and cherished early film, in particular—and there is currently nothing else quite like it. It is especially necessary in an era of disposable content. TCM is a place that values film for cultural reasons. It’s also, it should be noted, a sensible product in the streaming era, even if it’s not producing new intellectual property. As Vulture’s Josef Adalian wrote, the network “has always been a monetization engine for its owners: It takes long-ago produced content (much of it owned by WBD), smartly packages it with context and curation, and then rakes in millions in subscription fees from cable operators. Aren’t execs like Zaslav always going on about their precious IP and how much they want to reboot, reimagine, and otherwise exploit it?”

At the same time, TCM also offered a more ineffable service to American culture. “I think these companies that are led by these rich men—it’s mostly rich men—have a responsibility,” Telaroli said. “They’re the guardians of these pieces of art, and they should have a conscience about it and care about it. That’s a part of it. It think also we really do need to think about how we support work and what work we support and what we’re doing with our own time.”

This isn’t the first network Zaslav has disrupted. Changes made at CNN after the completion of the Time Warner–Discovery merger in April last year have tanked the network’s ratings. Chris Licht, Zaslav’s handpicked chief, failed disastrously and was let go after a humiliating Atlantic profile was published earlier this month. Zaslav and Licht’s shifts to the network—attempts to make it more “serious” and appealing to moderates and conservatives; a Donald Trump town hall—failed to catch on. Its ratings in May were lower than they had been in years.

There were briefly signs that Zaslav was heeding the TCM outcry. On Thursday, The New York Times reported that no further changes were expected at the network and that its hosts would stay on and that viewers would see “little to no change.” And yet further reporting a day later suggests that may not be the case: TCM’s staff of 90 had been cut to 20. (A WarnerBros executive disputed the figure to The Wrap and insisted employment levels remain at pre-merger level, though some employees have their time divided among multiple networks.) It’s difficult to imagine how the network could go on unchanged with such a skeletal team. At the very least, its efforts to continue to protect and preserve Hollywood history should clearly be compromised going forward.

That’s a tragedy for American culture—and maybe for Zaslav too. “There is something to be said for TCM’s legitimacy as a loss leader—or maybe just a not-huge-profit-generator—because of the perception it creates for the brand, for the relationships it forges with filmmakers,” Dieringer said. “Even if you want to look at it in a purely cynical way that has nothing to do with the love and art of filmmaking. I think just for him as CEO, the optics of being on the good side of people like Scorsese and Spielberg is really important. And Turner Classic Movies is a huge part of that.”

Instead, Zaslav is embracing his role as a cultural vandal and is torching a crucial institution. The bloodletting may have ceased, but only just for now.