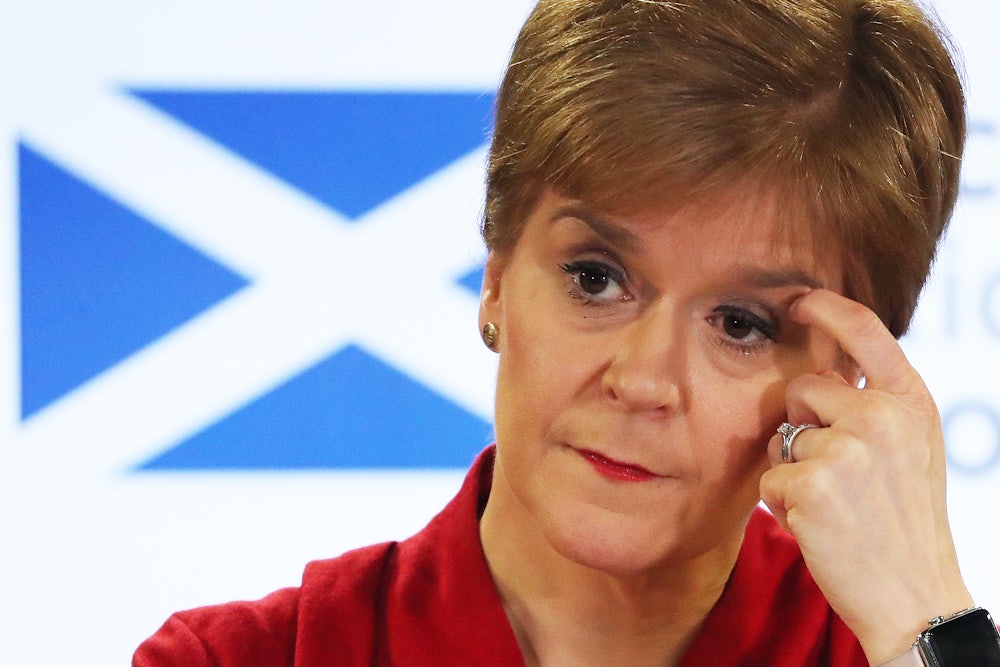

Scottish police arrested Nicola Sturgeon, the nation’s former first minister, as part of an inquiry into misspent party funds last week. She was later released without formal charges. Members of the Scottish National Party, or SNP, did not threaten a violent uprising over the arrest of their former leader. They did not make threats against law enforcement or other civil servants. Angry protesters did not gather outside the local constabulary, decrying a witch hunt. Scottish politicians did not make allusions to potential political violence against their opponents.

After her release, Sturgeon asserted her innocence without maligning her investigators or making unfounded accusations of political retaliation. “To find myself in the situation I did today when I am certain I have committed no offence is both a shock and deeply distressing,” she said in a statement released on Twitter. “Innocence is not just a presumption I am entitled to in law. I know beyond doubt that I am in fact innocent of any wrongdoing.” She also did not threaten to retake power and prosecute her rivals in revenge.

That is how things work in a normal democratic society. Scotland is no stranger to the ups and downs of democratic governance, of course. It unsuccessfully sought independence from the United Kingdom in a 2014 referendum amid promises from the major party leaders that have since gone unfulfilled. A majority or near-majority of its people want a second bite of the apple after the British departure from the European Union in 2016, which Scottish voters strongly opposed, and an anemic decade of Conservative Party rule in London. The British government refuses to allow a second referendum, for obvious reasons, and British courts recently shut down an attempt to hold one without Westminster’s permission.

And yet Sturgeon’s arrest sparked nothing remotely comparable to the reaction last week among former U.S. President Donald Trump’s supporters regarding his indictment on federal charges. Kari Lake, a Trump ally who lost the race to be governor of Arizona last year (and still falsely insists her victorious opponent cheated), publicly suggested over the weekend that there would be violence against top Justice Department officials and the news media if they “lay a finger on President Trump.”

“If you want to get to President Trump, you’re going to have to go through me, and you’re going to have to go through 75 million Americans just like me,” she told a crowd of supporters. “And I’m going to tell you, most of us are card-carrying members of the NRA. That’s not a threat, that’s a public service announcement.” (It sounded more like the former than the latter.) Even more responsible Republican leaders are fulminating over the indictment, claiming that it was a despotic abuse of power.

“The Biden administration’s actions can only be compared to the type of oppressive tactics routinely seen in nations such as Venezuela, Bolivia, and Nicaragua, which are absolutely alien and unacceptable in America,” Utah Senator Mike Lee said in a statement after Trump’s indictment. “It is an affront to our country’s glorious 246-year legacy of independence from tyranny for the incumbent president of the United States to leverage the machinery of justice against a political rival.”

This is nonsense, of course. Democratic countries do not prosecute their own leaders often, but they can and have done it before. Holding leaders accountable for their alleged crimes is a sign of a healthy democracy, not a failing one. One of the major parties conflating the actions of dictatorships and illiberal democracies with the federal prosecution of a lawless former president is a grim sign of how far American democracy has fallen.

Sturgeon’s arrest came as part of a police inquiry into her party’s financial woes. Roughly 600,000 pounds sterling (just under $755,000) is unaccounted for in its treasury, which should have swelled as more Scots drifted into the pro-independence camp in recent years. In addition to Sturgeon, Scottish police had previously arrested and questioned the two other signatories on the SNP’s financial records: former party leader Peter Murrell, who is Sturgeon’s husband, and former party treasurer Colin Beattie.

The Scottish legal system works a little differently from its U.S. counterpart. An arrest for questioning strongly suggests there could be a prosecution, but it by no means guarantees that one will happen. Some restrictions on reporting and public disclosure now kick in on Sturgeon’s behalf to avoid influencing a potential jury, reflecting the assumption that she may be tried for her role in the matter. “Scotland is not the United States, for example, where pundits merrily speculate about the guilt or innocence of a suspect long before the case goes anywhere near a jury,” BBC News archly noted in an explainer on Sunday.

This is also not exactly new territory for Scotland. Sturgeon is the second consecutive first minister to encounter the criminal justice system. Her predecessor, Alex Salmond, who served as first minister during the 2014 independence referendum and stepped down after its failure, resigned from the Scottish Parliament in 2018 amid allegations of serious sexual misconduct. Police charged Salmond with 14 counts related to alleged sexual assault, but a jury acquitted him in 2020, sparking a political scandal that weakened Sturgeon’s hold on the party.

Other examples of democratic countries prosecuting their former leaders abound. Nicolas Sarkozy, the former president of France, recently received a three-year prison sentence for corruption charges. He has yet to start serving it while his appeals process unfolds. The Fifth Republic still stands. Former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, who died on Monday, went through so many investigations, prosecutions, and trials throughout his political career that I will not even attempt to summarize them. Italian democracy remains largely intact.

In South Korea, two presidents—Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye—have been arrested and tried on corruption charges within the last decade. Lee received a 15-year prison sentence; Park received 20 years. (They have both since been pardoned.) Some countries also fear impunity more than indictment. Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu, who returned to power in an election last year in part to avoid a corruption indictment, faced massive nationwide protests over his since-halted plans to remake the judiciary in his own image.

It is true that no sitting or former U.S. president had been formally charged or indicted for a crime before Trump, but that was largely because of the vicissitudes of history rather than any formal norm of impunity. Former President John Tyler, for example, was elected to the Confederate House of Representatives and could have theoretically been tried for treason had he not died before the Civil War’s conclusion. Richard Nixon would have beaten Trump to the dishonor of the first presidential indictment had Gerald Ford not pardoned Nixon to expressly prevent it. That mistake cost Ford reelection in 1976—perhaps the clearest signal the American people could send about presidential impunity.

Nor can it even be said that impunity for top political figures is some sort of ancient tradition handed down to us by the Founders, as Lee suggested in his statement. In 1807, Thomas Jefferson ordered the indictment of his former vice president Aaron Burr for treason, citing an alleged plot to conquer the newly acquired Louisiana Territory and form an independent nation in the then-western United States. Burr had previously been charged with murder in New York for his famous duel with Alexander Hamilton, but he evaded prosecution until the charges were dropped.

Despite Trump’s claims to the contrary, there is no evidence that he is a victim of prosecutorial misconduct or abuse. It’s not like the Justice Department forced him to take dozens of classified documents with him after he left office, haphazardly store them around Mar-a-Lago, or (allegedly) lie to a grand jury about returning them after receiving a subpoena. Unlike the campaign-finance case Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg brought against Trump earlier this year, the federal prosecution is on solid legal footing.

There is also nobody in American politics who has done more to advance the argument against an impunity norm than Trump himself. The former president campaigned on the idea that he would “lock up” Hillary Clinton and pressured the Justice Department to do it, an effort that only faltered because the department did not abandon its ethical obligations. In a statement on Monday on Truth Social, his post-Twitter sounding board, Trump even threatened to appoint a “special prosecutor” to expressly target Biden and his family members.

What’s striking, of course, is not any similarity between the case against Trump and the cases against Sturgeon (and other world leaders, for that matter). It’s the difference in how they responded. Conservative media outlets, Trump loyalists, and Republican officials have primed a large section of the American electorate to believe that holding him accountable for his crimes is inherently illegitimate and, in some circles, that violence is an appropriate response. That, not the prospect that Trump will face a few years behind bars, is a far greater threat to the republic.