In “Wings,” a story from Lorrie Moore’s 2014 collection, Bark, KC, a failed musician, muses on what it might be like to die. She’s been spending time—arguably too much time—with her elderly neighbor Milt, and she has mortality on the brain.

KC herself imagined dying would be full of rue: like flipping through the pages of a clearance catalog, seeing the drastic markdowns on stuff you’d paid full price for and not gotten that much use from, when all was said and done. Though all was never said and done. That was the other part about death.

The passage is trademark Moore, blending the tragic and the comic, the serious and the pointless. Its tone is wry, almost weary, as if KC is older than her 38 years. There’s an elaborate simile that expands over the course of a sentence. There’s a cliché (“when all was said and done”), followed quickly by a riff on the cliché (“all was never said and done”). And there’s a dark turn near the end of the passage, the realization that the dying, no matter how old they are, always leave this world too soon.

Untimely deaths have been a consistent theme in Moore’s fiction. In her first collection, Self-Help (1985), Moore, then in her twenties, related the inner thoughts of a young mother whose terminal cancer has spread “like a clumsy uninvited guest.” In her follow-up collection, Like Life (1990), a 35-year-old woman named Mamie spends her days looking for a place to live and her nights dreaming about places where it’s acceptable to die. Two of Moore’s strongest stories, both from Birds of America (1998), are about the imminent deaths, or the narrowly avoided deaths, of children. “Dance in America” describes a spirited fourth-grader with cystic fibrosis, while “People Like That Are the Only People Here” takes place in a pediatric oncology ward. These last two stories represent Moore at her best: unflinching, insouciant, morbidly funny. She manages to do with her prose what the narrator of “Dance” claims to do with her body: to show “life flipping death the bird.”

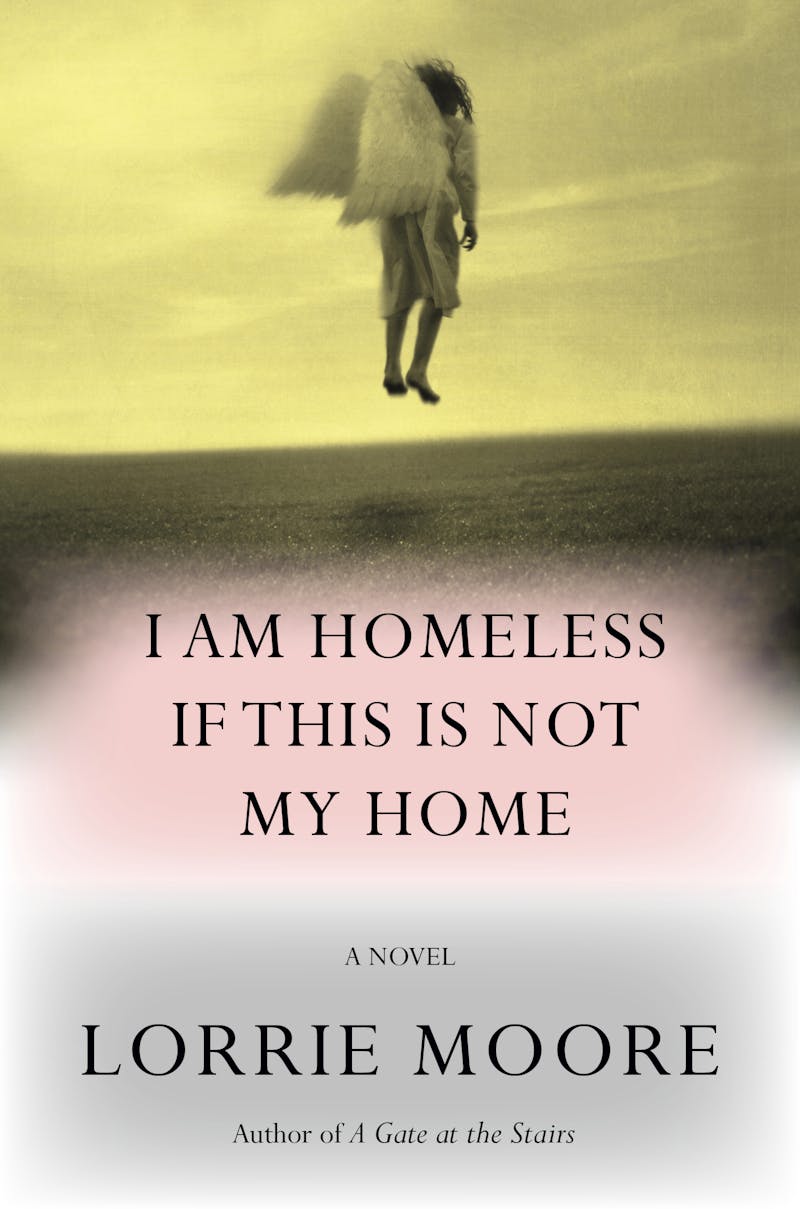

It’s no surprise, then, that her most recent work of fiction, I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home, describes two characters dying before their time. There’s Max, a middle-aged father with late-stage cancer, and Lily, a charismatic, mentally ill woman who ultimately takes her own life. They are linked through Finn, a cranky schoolteacher, who is Max’s younger brother and Lily’s ex-boyfriend. Over the course of the novel, Finn toggles between these two dying, then dead, intimates. At its end, he’s left alone to grapple with loss.

And yet the novel is tonally and stylistically quite different from the works that have preceded it. I Am Homeless doesn’t have the antic energy of Moore’s early novels, nor the combination of dismay and exuberance that we find in many of her short stories. The pacing is slow; the tone is muted, questioning, almost sincere. Moore has spent much of her career chronicling the familiar conflicts and indignities of contemporary middle-class life in the United States, but in this novel, she dispenses with many of realism’s conventions. Strange events occur: People have premonitions; the distant past bleeds into the present; a dead body returns to life.

Moore doesn’t seem quite at home in this mode. Encounters with the spiritual world are awkward rather than unnerving; plots intersect without clear meaning or effect. One can’t help but miss the snappy dialogue and the sharp observations that characterize so much of Moore’s fiction. This latest work, by contrast, is jarring, repetitive, at times a little boring. But then—who can say?—perhaps death is as well.

Moore has dabbled in the fantastic before. Her first novel, Anagrams (1986), shifted between a central plot and the imaginings of Moore’s characters. The protagonist, Benna, has an imaginary six-year-old daughter, and much of the novel is given over to describing their interactions in great and moving detail. With its multiple frames and shifting points of view, the novel is less magically realist than it is postmodern. More recently, with “The Juniper Tree,” from Bark, Moore attempted something like a ghost story: The narrator of the story visits the house of a just-deceased friend, only to find the woman herself in the living room, waiting for her friends to bid her farewell.

But Moore has never before so thoroughly blended the historical and the contemporary, or the real world and the spiritual one, as she does in I Am Homeless. The novel begins with a subplot: A woman running a boardinghouse in the postbellum U.S. South describes, in a letter to her sister, her efforts to manage a handsome, lecherous boarder. Though the language of the letter is straight out of the nineteenth century (we read of “varmints,” “nightjars,” and a “desk cartonnier”), the writer’s sensibility is strikingly modern, suggesting that Moore isn’t after historical accuracy. We then switch to the contemporary moment and to the novel’s central plot. It’s the fall of 2016, and Finn, on leave from the private Midwestern high school where he teaches, has come to New York to see Max, now in hospice, through to the end of life.

The first third of the novel tracks Finn’s efforts to perform the role of “death doula.” We learn what it’s like to sit beside the dying. Finn, aiming to distract, tries to get Max to chat about childhood memories and the Cubs’ World Series prospects. Max—thin and hairless, his skin “buttery” and apricot-hued—snaps in and out of cogency. “His stare sometimes fixed itself pensively into the middle distance, as if he were looking into his own grave,” Moore writes. Finn feels himself to be at once essential and useless. How can he communicate meaningfully with his brother at this moment? Can he—should he—convince Max to hang on just a little longer?

While wrestling with these questions, Finn gets a text message from Lily’s friend Sigrid: “Come home,” it reads. “Urgent matters.” Still loyal to Lily, and unconcerned that she’s been dating another man, Finn leaves “the bardo of the hospice to its trapped souls and the steel beds and alarmingly colored drinks” and begins the long drive west, thinking, with “an illogical sense of hope,” that Max will wait to die until his return. It’s not quite clear what we’re supposed to make of Finn’s decision: Is he admirably devoted to Lily? Or is he fearful and flighty, leaping at any excuse to leave a difficult vigil? Many hours and one car accident later, Finn makes it to Sigrid’s house, where he learns that Lily, recently institutionalized, has managed to drown herself in the shower. She’s already been buried, in a “green cemetery” where her body can degrade.

Much of what follows represents Finn’s effort to prove his and Lily’s enduring love, death and its permanence be damned. “You and Lily were never on the same page at the same time,” Sigrid says, as part of an elaborate seduction scheme. Finn, for his part, believes that he and Lily “were water birds who’d mated for life—and yet often conducted their lives separately in another part of the meadow or the pond.” He drives to Lily’s grave, where he finds his ex resurrected:

There was Lily, standing in the dead fleabane … her shroud draped around her, a cocooning filthy gown. She seemed to have emerged from a mist that still swirled about her feet.… She smiled at him with a mouth full of dirt, her face still possessed of her particular radiant turbulence—yet watery, as if he were seeing not so much her face but its reflection in a pond. Her eyes were the dead bone buttons of a white dress shirt. Then suddenly color, their greenish gray, washed into them.

There’s some lovely writing here—“the dead bone buttons of a white dress shirt” is especially nice—though it may be too lovely for what it describes. Lily is not a ghost but a dead body, temporarily revivified and subject to decay. (Later, Finn must carry her in and out of a truck stop; later still, he washes her gently, replacing her skin as it sloughs off.) It’s Finn’s love, we realize, that colors the narration, rendering the dead body beautiful again. The two embark on a madcap road trip south, to a forensic research facility—a “body farm”—in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Here is where the novel stagnates. Finn and Lily banter—about funeral songs, jokey epitaphs, Schrödinger’s cat—but their dialogue lacks the crackle that so often exists between Moore’s romantic couples. Again and again, Finn asks Lily why she wanted (wants?) to die; again and again, she rebuffs him, saying he can’t understand. She’s vague and evasive about the afterlife; rather than demystifying death, she makes it sound even more unknowable and strange. Moore describes Lily’s dead body repeatedly: Her ribs are like “the slats of venetian blinds behind the translucent voile of her skin”; her body after a bath resembles “the rice wrap on a spring roll, the bean sprouts and chopped purple cabbage visible inside her.” The images are beautiful, but they pile up purposelessly, like so many items in a landfill.

Somewhere in or near Kentucky, Finn and Lily spend the night at an inn—a “decrepit manse” that turns out to be the boardinghouse from the novel’s opening letter. (Other letters from this writer, Elizabeth, are interspersed throughout.) The woman at the front desk claims the house isn’t haunted exactly; it just carries a lot of Civil War history. We later learn that Elizabeth killed the lecherous boarder in the bathtub—perhaps the same bathtub in which Finn bathes Lily—and that the sister she’s been writing to is also dead, her ashes used as a deicing agent.

It’s possible to track the parallels between these two, intersecting narrative timelines: There are two siblings in mourning or in proto-mourning, two seducers, two women whose dead bodies are or soon will be, in Elizabeth’s words, “put to good use.” But what does the Civil War have to do with Lily and Finn? Are the many mentions of Lincoln intended to remind us that, in the narrative present, a less noble figure will soon assume the presidency? Is Elizabeth’s murderous action a kind of #MeToo move, made some 150 years in advance? The novel invites us to speculate about the resonances between the postbellum era and our own, but they’re not easily identified. The plots tangle like matted hair.

Finn eventually drops Lily at the body farm, shocked that his beloved, given something like a second chance, still chooses to die. Lily insists that death is all around us and we would do well to accept it; Finn makes the case for staying attached to life and to those you love. He’s angry at Lily: for wanting to die, and for dying now, when his brother is dying as well. “He could feel now that his brother was dying right then at that very moment, just as he uttered these words,” Moore writes. “He could hear the last pounding of Max’s heart on the hard door of time.” It’s another moment of synchronicity, two deaths happening simultaneously. Finn witnesses Lily’s but not his brother’s. Despite the promises he made to Max of fidelity and companionship, Finn has left his brother to die alone.

What do we owe our siblings? It’s not a commonly asked question—we’re more likely to ask what a child owes a parent, or what one spouse owes another—but Moore has posed it in each of her four novels. In Anagrams, Benna wonders how affectionate she needs to be with her awkward, disheveled brother Louis. In Who Will Run the Frog Hospital? (1994), the protagonist Berie comes to regret the cruelty she showed her foster sister, LaRoue; the latter dies by suicide before Berie can fully make amends.

In A Gate at the Stairs (2009), her messiest yet richest novel, Moore provides her most sustained exploration of the sibling bond. Tassie, an undergraduate at a prestigious Midwestern university wrapped up in her own problems, ignores advice-seeking emails from her younger brother, Robert. Without any guidance from his sister, Robert decides to enlist in the Army. He’s shipped off to Afghanistan during the early phase of the so-called war on terrorism and dies almost immediately. At the funeral, Tassie climbs into Robert’s coffin, pushing aside the body parts stuffed with Styrofoam and newsprint; she stays curled next to her brother, or what’s left of him, until moments before the coffin is lowered into the ground. It’s a haunting image of sibling love, and it’s stayed with me for a long time.

Max’s funeral, which owes something to Robert’s in Gate, is equal parts unbearable and absurd. “The service seemed to bear no resemblance to the story of his brother’s life,” Finn reflects. “Scripture continued to be read nonsensically. There were more psalms set to music.” When Finn finally has the chance to speak, he rambles about Max’s essential goodness and “beautiful stoicism,” about his own failures as a younger brother, and about how the “mind-meld of brothers had kept them connected,” such that Finn knew the exact moment that Max left this Earth. Finn sees worried faces in the pews. “He knew then that he sounded insane to absolutely everyone.”

When I first read that line, I took it as an indication of how difficult it is to communicate the intricacies of sibling love to a group of strangers. When I read it a second time, I thought it might undermine most of the novel that’s preceded it. Is Finn actually insane? Was his sojourn with Lily a fantasy, or a dream, or perhaps a metaphor for the metaphysical journey his brother is about to take? Was Lily herself nothing more than a “thought experiment,” as she jokes at one point?

I’m not sure these questions can be answered definitively, and, more importantly, I’m not sure the answers matter. Present or absent, sane or not, Finn can no more know what his brother’s last moments were like than he can know what it feels like to a zombie or a ghost. Death remains a mystery to the living, no matter how close they get to the dying or to the dead.

At Lily’s funeral, Finn realizes that “all the people who had ever loved him” are gone. “And in feeling their absence he felt his own self pitted, burnished, caressed, then given a shove off a cliff,” Moore writes. He contemplates joining the departed, thinking that no matter what the afterlife holds, he might be happier among those he knows. Instead, he resigns himself to living. He goes on dates; he returns to teaching. He also starts volunteering at a local hospice, where he holds the hands of strangers as they prepare to leave this world for another.

It’s a quiet, discomfiting ending, and it lacks the consolation that Moore has provided in the past. There’s no ecstatic dancing, no surprise reunion, no refuge taken in the body of another. (Finn dances awkwardly with Max’s widow at the funeral, but he restrains himself from burying his face in her hair.) It’s as if Moore is fresh out of compensatory tricks. Life is sad and lonely, she suggests; the people you love will abandon you, and you’ll abandon them in turn. You end up living among strangers until it’s your turn to leave. Reading the novel, I was reminded of a kind of refrain that comes up a few times in Anagrams: “Life is sad. Here is someone.” Thirty-seven years later, it’s time to update the sentiment: Life is sad. There’s no one here.