America’s largest, fastest-growing political party isn’t led by Joe Biden or Donald Trump. It’s the Independent Party. At least, that was one of the biggest takeaways from a Gallup poll this spring. It found that 49 percent of Americans—roughly the same amount as the number of voters who identify as Democrats and Republicans combined—think of themselves as “independents.” (An identical poll a month later found slightly less eye-catching numbers.) That’s a huge jump from just 20 years ago, when less than a third of respondents identified that way.

But what’s going on behind those numbers? Many in the political press jumped on them as the latest evidence of partisanship’s negative effects. “We spend our days captivated by people with the most power and the biggest mouths,” wrote Axios founder Mike Allen in April. “But it turns out a rising number of Americans want something else—political independence.”

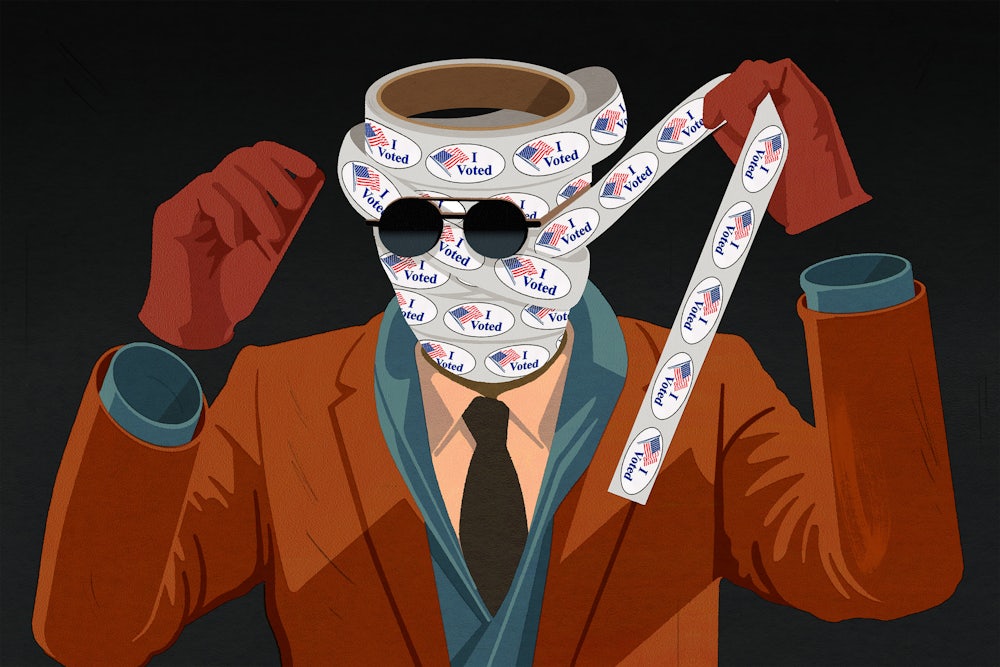

“By far the dominant U.S. party isn’t Democrats or Republicans,” he continued. “It’s: ‘I’ll shop around, thank you.’”

It is true that the rise of independents—and the assumption that a silent majority wants something quite different from what they’re being offered by the two—is beginning to have ripple effects. In December, Arizona Senator Kyrsten Sinema announced she was leaving the Democratic Party to become an independent, hoping voters in her state would recognize and reward a maverick who was as fed up with politics as they were. (She is currently polling behind both the leading Republican and Democratic challengers for her seat.) And then there is No Labels, the centrist political group recently in the news for its “toxic” work environment and its employment, until March, of disgraced pundit Mark Halperin. That organization, which ostensibly exists to push “bipartisan” policies, has been seeking to get itself on the ballot in more than a dozen states. Its ultimate goal is to push a “unity” ticket featuring one Democrat and one Republican—to woo independent voters who hate both parties, of course.

And then there’s Andrew Yang, the successful businessman who has run two highly unsuccessful campaigns as a Democrat—one for president in 2020, and another for New York City mayor in 2021—and launched the Forward Party, aimed at wooing the nation’s weary voters, last July. “The United States badly needs a new political party—one that reflects the moderate, commonsense majority,” Yang and his backers wrote in a manifesto. The party’s motto—“Not left. Not right. Forward”—envisions an electorate of tens of millions of Americans who are not Democrats or Republicans but are, instead, shopping around.

Except … that really isn’t the case. “The interesting thing about independents is that they do have affiliations to political parties,” said University of Michigan political scientist Yanna Krupnikov—who, with the University of Arizona’s Samara Klar, literally wrote the book on political independents, 2016’s Independent Politics: How American Disdain for Parties Leads to Political Inaction. “They typically have a preference, but it’s potentially different from the deep-seated attachment that a strong partisan might have. But a large portion of them do seem to prefer one party or the other.” Roughly three-quarters of independent voters are known as “leaners”—they typically turn out to vote for one party or the other. Most independents, in other words, aren’t so independent.

Rather, “I think what this reflects is that most Americans have a pretty negative view of the party system in general and of what’s happening in our politics,” Emory University political scientist Alan Abramowitz told The New Republic. “There’s a reluctance to openly identify oneself as a partisan and to say, come right out and say, ‘I think of myself as a Republican or a Democrat.’”

It’s also possible that some folks just like saying they’re independent, whether they really are or not. “Consider the word itself. ‘Independent’ sounds so empowering, so liberating, so … American,” noted Daniel de Visé in The Hill earlier this year.

Self-described independents and leaners do have one thing in common. “Even among people who identify with a political party … the trend is in their disdain for the other party,” said Matt Grossmann, director of the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research, or IPPSR, and professor of political science at Michigan State University. “That is actually especially true of leaners, that they don’t have a strong positive feeling about the party that they lean toward; they just have a negative feeling about the party that they lean against.”

Indeed, more than 60 percent of independents who lean Republican or lean Democrat have “very” or “somewhat” cold opinions of the other party, according to a 2017 Pew Research poll. These voters typically end up voting for Democrats and Republicans simply to ensure the party they detest more isn’t in power. “You might have many people who are willing to show up and vote, but they’re not going to encourage others to do so,” Krupnikov said. “They’re doing it in a way where they’re trying to avoid seeing the lesser of two evils, which in some sense is a sad choice to have: You’re dissatisfied with everything.”

In other words, it’s negative partisanship, an increasingly powerful part of American politics over the last 40 years. In 1980, the average Democrat and Republican thought that the other party was basically fine; in the four decades since, those feelings have evaporated.

Writing in FiveThirtyEight in 2020, New America’s Lee Drutman made the case that several interlocking factors have contributed to the mushrooming negative partisanship. “The first is the steady nationalization of American politics,” he wrote. “The second is the sorting of Democrats and Republicans along urban/rural and culturally liberal/culturally conservative lines, and the third is the increasingly narrow margins in national elections.”

Many see the acrimony and bickering that defines much of American politics as a result of these trends and simply want to withdraw. “Sometimes socially it’s easier to say that you’re independent or apolitical because it gets you out of jams—you don’t have to talk politics,” Krupnikov said. “This is an important aspect of this, especially as politics become more and more contentious. Some people want to pull themselves out of that particular context.”

To be clear, there are some genuine independent voters out there—a minority of independent identifiers who really do flip between parties from election to election. And some leaners are partisans without a party. Some are independent because they’re very conservative and don’t believe the Republican Party is conservative enough, or they’re very liberal and don’t believe that the Democratic Party is truly progressive. “There still are true independents in the middle, and they’re just people who really don’t pay much attention to politics,” Grossmann said. “If they vote, [they] don’t tend to make up their mind until late in the process.” And the numbers of swing voters are not increasing, said Grossmann. “Where you’re seeing the increase is in these folks who do know kind of what side they’re on but don’t want to say it.”

Many of these voters have expressed a desire to vote for a third party. In 2022, Pew Research found that 43 percent of surveyed voters disagreed with the assertion, “I usually feel there is at least one candidate who shares most of my views,” up from 36 percent four years earlier. Nearly half of independents—and 38 percent of Democrats and just 21 percent of Republicans—strongly agreed with the statement, “I wish there were more political parties to choose from in this country.” There are, however, reasons to suspect a third party aimed at hoovering up independents would fail. For one, the United States has been a political duopoly for more than a century, and there are no signs of disruption. For another, frustration with the political system is the one thing most independents share. Aside from that, there are few indications that these people represent a true coalition that could viably compete with the two entrenched parties: Contra the assumptions of Andrew Yang and No Labels, it’s wrong to imagine that the vast majority are “centrists.”

Meanwhile, negative partisanship has dramatically changed the tenor of U.S. political campaigns over the last four decades. Rather than pitches to persuade voters—and again, who knows how many persuadables really exist—the campaigns are built around constant reminders that the other guy is worse. Much, much worse.

This will likely be truer than ever in 2024. Both Biden and Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee, are “unpopular.” The goal of the campaigns will not be to convince voters that each candidate’s policy platform is best, or that he has the temperament to run the nation, but to convince them that the other guy is corrupt and crazed. Biden will likely (rightfully) lean on the fact that his opponent is a delusional authoritarian who wants to suspend the Constitution and install himself as a dictator; Trump will likely respond by claiming that his opponent is simultaneously senile and overseeing a vast conspiracy to enrich himself and his family at the expense of the nation. And voters—independents as much as nonindependents—will respond, because that’s simply how powerful negative partisanship is.

Regardless, the idea that these voters are a secret army of moderates waiting to be unlocked by a centrist party is likely a myth. Many do think the parties are too extreme; certainly most believe that they’re too disputatious. And yet they hardly represent a sizable “third party”: They’re not shopping around.