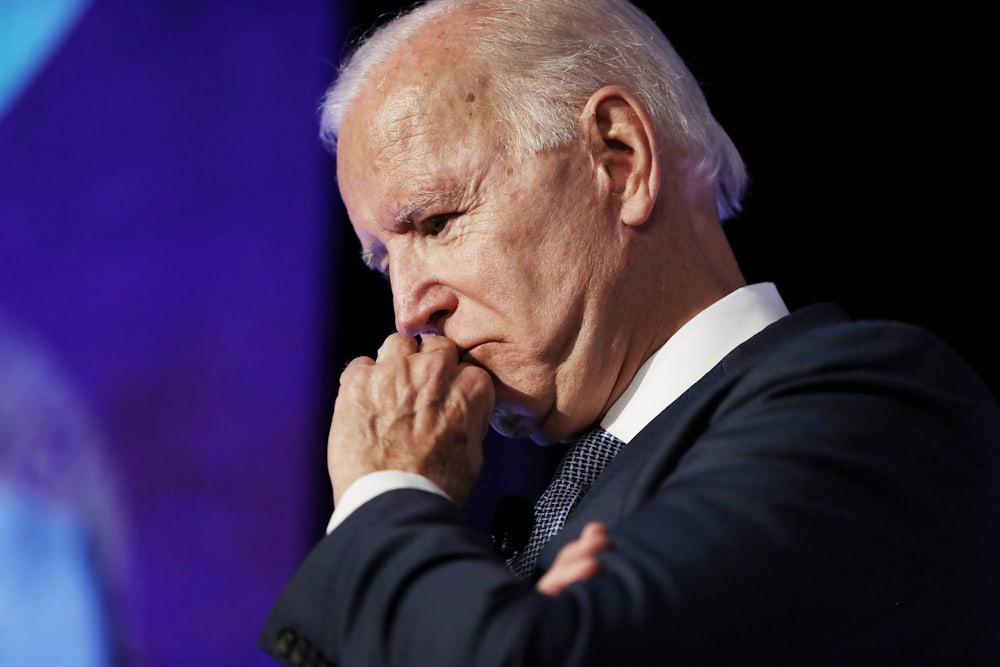

The good news about the agreement on the debt ceiling President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy struck is that it’s probably the best deal Democrats could have gotten. Biden can sell his party on the fact that the deal falls far short of the draconian demands made by the GOP’s right flank—who had previously been running the show and are now incensed at being left behind. Democrats had spent much of the debt negotiations on their back foot; now Republicans are in disarray. Similarly, Biden can once again sell voters on the fact that he’s a sober dealmaker committed to keeping the government functioning, not the fire-breathing ideologue or doddering vegetable that Republicans typically portray him as. There’s not much to celebrate in this deal, but Biden can pitch it to both skeptical members of his party and the public as a necessary compromise: Once negotiations with McCarthy began, this was probably the best deal he could have struck.

The bad news is that he made a deal at all. Everything that’s good about this deal, provided it passes, occurs in the short term: The government doesn’t default; the United States only suffers minor reputational harm. Generally speaking, avoiding apocalypse—and default could have caused something close to that—is a good thing. But by negotiating with McCarthy, Biden legitimized what were effectively terrorist tactics and dramatically increased the likelihood of an apocalyptic event in the near future. Republicans can and will continue to hold the debt ceiling hostage; the expectation, thanks to Biden’s willingness to engage, is that concessions will follow—or else the U.S. defaults.

This is a clear deviation from recent Democratic strategy, and it is a potentially devastating one. In 2011, Barack Obama got played by Republicans: He thought they were negotiating about raising the debt ceiling in good faith; they weren’t. Realizing this too late, he submitted to steep, multitrillion-dollar cuts—ones that were devastating to a still-anemic postrecession economy—in order to avoid default. Having realized that Republicans had no interest in legitimate bargaining, however, Obama set what should have been the ongoing precedent: Don’t negotiate over the debt ceiling. It worked—subsequent fights over raising the debt ceiling avoided concessions. The lesson has been clear: If you want to win, don’t play the game.

Biden paid lip service to this strategy, repeatedly making public statements to the effect that raising the debt ceiling was nonnegotiable. This is a reasonable stance. For one thing, Republicans have always voted to raise the debt ceiling when they are in power. For another, it is existential: It must be done so the U.S. government can continue to function. Failing to raise it, moreover, would catastrophically damage America’s reputation abroad and potentially blow up the economy. Republicans were putting a gun to the head of the American—and perhaps global—economy, and they were doing it for base, political reasons. The only responsible thing to do was to ignore them.

This was also good politics for Biden. He was betting against Kevin McCarthy, something few have gone broke doing. McCarthy’s caucus is unruly; getting his seat as speaker of the House required major concessions to his most unhinged members. Biden made a calculated bet that McCarthy couldn’t put together a package that could serve as a starting point for negotiations, a bet he ultimately lost. McCarthy did produce one—an unworkable, ridiculous budget and one that showed the Republican Party’s eagerness to slash necessary social programs relating to health care and education—by the skin of his teeth last month.

But McCarthy and Republicans had also made a bet about Biden: that he would cave. Biden likes negotiating too much; his statements about not negotiating were resolute, but there was a hint of squishiness—Biden kept leaving openings for possible negotiations. After McCarthy and House Republicans passed their budget, that’s exactly what happened. Biden played ball. And while, yes, he won the negotiating battle, he lost the debt ceiling war.

That’s largely because Republicans can come back to the table the next time the debt ceiling is up for raising in a divided government and ask for, well, anything. As New York’s Jonathan Chait writes in a perceptive piece about the implications of this deal, “given that Republicans have probably cut domestic discretionary spending as low as they can tolerate if not lower, the next round of demands will likely cut deeper into anti-poverty programs that were spared this time. Or possibly, Republicans will creatively demand concessions on immigration, abortion, or any other social issue that has seized their imagination at the moment.” There’s simply no telling where this will lead, but none of it is reassuring. Now opened, this Pandora’s box is going to be almost impossible to close.