In early May, students, librarians, mental health counselors, adjuncts, and tenured professors gathered in the LaGuardia Performing Arts Center to speak to the City University of New York’s board of trustees. Fresh from a picket line at LaGuardia Community College, those assembled spoke their minds with tones that ranged from temperate to unrestrainedly angry as they testified to the devastating toll that decades of disinvestment has taken on the largest urban university system in the United States. The consequences of this chronic neglect: overstuffed classrooms, meager provision of support and services, poverty wages for faculty and staff, peeling paint and falling debris. Members of PSC-CUNY, the Professional Staff Congress union representing 30,000-some faculty and staff, placed silhouetted signs in empty seats that read “Missing Adjunct,” “Missing Adviser,” and “Missing Student,” a visual symbol of all those who have had to leave the system as a result of unrelenting austerity.

Naomi Schiller, a professor of anthropology at Brooklyn College, spoke about a student named Angela whom she had advised just that day and who was the first in her family to attend college. “What came up again and again were the many ways that the leadership of this university is failing her,” Schiller said.

“Our financial aid office is so understaffed that it can’t figure out if she has the funding to take summer classes. The advising office has struggled to reach students, so she’s not aware of expensive new software she’s supposed to use to monitor her academic progress. Angela takes classes in rooms that are much too hot. Three of her five classes are taught by adjuncts. Only one paid office hour a week is not nearly enough to meet her and her classmates’ needs. A strange black goo is leaking from the ceilings of some of our lab spaces.” When she and her student charge finally got down to discussing topics related to class, they discovered that the journal articles Schiller recommended Angela read were no longer available to her through CUNY’s subscriptions.

When Schiller told Angela that the board of trustees had announced $100 million in cuts to CUNY in 2024, Angela responded, “I guess they just don’t care about us—but honestly, it doesn’t surprise me.” And there are few surprises in store for the beleaguered faculty, staff, and student body of the CUNY system, for they have seen the future laid out by New York City Mayor Eric Adams. The course that has been charted for what was once a higher education gem is one of demoralizing neglect.

As one might expect, many of the speeches delivered at the hearing came from those who’d divined this grim future and were on hand to deliver a rebuke to the February directives for CUNY campuses to slash their expenses by 5 to 6 percent, alongside the cuts to CUNY outlined in Adams’s proposed Fiscal Year 2024 budget. These cuts, as they currently stand, will amount to $41 million each year for the next three years, further straining the budgets of the 11 senior colleges, seven professional institutions, and seven community colleges that comprise the system—the last of which depend heavily on city funding. The budget is set to be finalized in June.

The cuts come on the heels of $155 million in reductions to CUNY’s funding over the past year; since June 2021, successive cuts have resulted in the elimination of 363 part-time and full-time-equivalent staff. The city’s rationale for deepening cuts to CUNY is that enrollments have declined in past years, but such are precisely the dire conditions under which funding should be reinforced, not scaled back. Since the beginning of the pandemic, full-time enrollment across CUNY has fallen by over 16 percent, a likely reflection of wayward institutional support and intensifying economic precarity that has hit CUNY students particularly hard.

“The mayor has been pretty brutal in his brief tenure towards CUNY, which has disproportionately harmed community colleges,” PSC-CUNY president James Davis said.

Maia Rosenberg, a member of Jews for Racial and Economic Justice who graduated from Brooklyn College last year, says that she chose to go to CUNY because it was the cheapest option. She studied linguistics and loves that CUNY is “a home to everyone regardless of their backgrounds.”

“I’d be in a classroom, and there was no majority demographic. There were people from immigrant families, people who are new immigrants themselves. There was a range of ages, a range of economic backgrounds.” Currently, around 60 percent of students who graduate from New York City’s public high schools matriculate at a CUNY campus. Seventy-five percent of undergraduates are students of color, and half come from families that earn less than $30,000 a year. The students at CUNY, Rosenberg said, are “a mini-version of the city itself.”

Nonetheless, evidence of the school’s financial starvation was ubiquitous during her time at Brooklyn College. During the pandemic, students dropped out because the childcare center was closed. Classes never got smaller as she progressed through her major. About three in four of her classes, she estimates, were taught by graduate students. When it came time to apply to graduate school, she struggled to summon writing samples because she had never been asked to write a longer paper and had trouble getting recommendations from tenured faculty members—because she hadn’t been taught by many.

Cuts to CUNY, and the fickleness of funding on a year-to-year basis, have accelerated budgetary asceticism at all levels. This is despite repeated evidence that CUNY has remained an unparalleled engine of social mobility. In 2017, a paper published by a team of economists led by Raj Chetty showed that CUNY catapults six times as many low-income students into the middle and upper class as all Ivy League schools, Duke, MIT, Stanford, and the University of Chicago combined.

“When I go to well-resourced institutions, and I’m in their buildings, I walk around and often think that our students are being set up to expect total dilapidation so that when they go to these elite spaces, it’s intimidating,” Schiller said. “It’s a class-based training in what to expect and where to feel comfortable in the world.”

Michelle Mei, who currently attends Hunter College and serves as a project intern at the New York Public Interest Research Group, or NYPIRG, a statewide student-directed nonprofit with chapters at colleges and universities across New York, says that she became involved with the fight for CUNY after it took her a month just to get an appointment with her adviser. When she consulted friends for advice, she found that they had the same problems. When she reached out over email for one-on-one counseling during the pandemic, she didn’t get a reply.

“If there was more funding for faculty and staff, we wouldn’t have to wait that long just to get a simple response. Sometimes the questions are really simple, but they can lead to deeper conversations,” she says.

Face-to-face time with counselors can mean the difference between receiving financial aid and missing a necessary form, finishing a major on time and not getting into a required class by the enrollment deadline. Yet students are regularly unable to meet with counselors in a timely fashion and turn to already overburdened teachers, librarians, and other staff for help. Max Thorn, a librarian at Queens College, testified at the hearing that students regularly visited with complaints of unreturned phone calls, ghosted emails, and tickets that disappeared with no explanation.

Also threatened by budget reductions are CUNY Reconnect, a program launched last fall to aid adults in returning to higher education, and Accelerated Study in Associated Programs, or ASAP, an enriched remedial program, founded in 2007, which provides academic and financial support for students who face barriers to higher education. The latter has a demonstrated track record of success, with enrolled students graduating at twice the rate of similar students.

That a university system suffering from such thorough undermining continues to demonstrate its quality is a testament to the greatness of CUNY’s history and those who remain loyal to bearing its torch today. But CUNY’s fruits have never been as broadly distributed as they could be. When the City College of New York was founded in 1847, it was the first free public institution of higher education in the country. Some who take a longer view of the history of CUNY argue that New York City has lost touch with its origins as the birthplace of free public higher education. They also suggest that its modern neglect by politicians is a backlash to the racial diversification of the system, which largely served white men for its first hundred years of existence.

In 1969, student activists spearheaded by African American and Puerto Rican students at CCNY, and inspired by broader Civil Rights–era mobilization, launched protests and strikes that succeeded in dramatically expanding access to CUNY, opening its doors to lower-income students of color. Their efforts made CUNY one of the first institutions to make public higher education free to all high school graduates. Yet barely a decade later, amid the throes of financial crisis, this halcyon era would come to a permanent end, when CUNY began imposing tuition for the first time in its history. Stephen Brier, a professor of urban education at the CUNY Graduate Center, wrote in the journal Radical Teacher, in 2017: “It is hardly an accident that CUNY’s free tuition entitlement ended a short half dozen years after the institution opened its doors to large numbers of students of color.”

A report issued by the CUNY Faculty Senate in 2019 surveyed faculty-to-student ratios at senior colleges across SUNY and CUNY. It found that over the past 17 years, CUNY enrollments had grown three times faster than faculty positions. Moreover, it found that campuses with the highest percentages of Black and Hispanic students had the lowest faculty-to-student ratios, suggesting that the disparity could be illegal under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

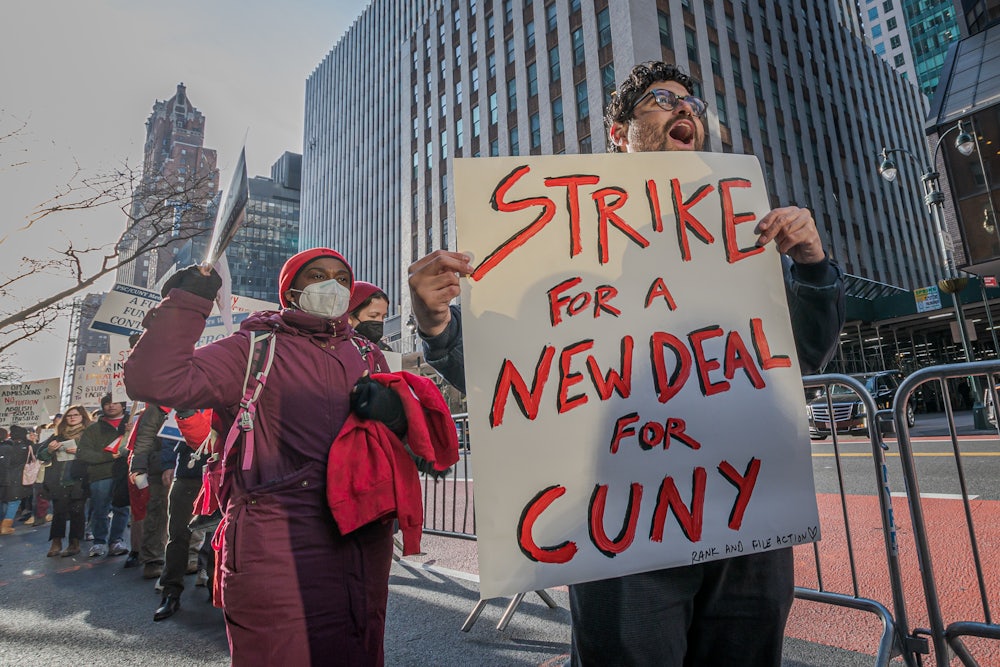

Advocates believe that the only way to restore the visionary and progressive ideal first embodied by CCNY—and by the rest of the system, which remained tuition-free for over a century after its founding—is for the state to commit to almost $2 billion in investments over the next five years as part of a New Deal for CUNY. Such an amount, they contend, would be necessary to make CUNY tuition-free, to instate higher faculty-to-student ratios, and to repair dangerous and decrepit infrastructure. They point out that the figure would only come to about three-quarters of 1 percent of the state’s annual budget, and would be the first step toward reversing the long-standing disinvestment that has brought CUNY low.

Tuition costs have risen dramatically: Since 2008, they’ve gone up by 73 percent at senior colleges and 71 percent at community colleges, though they’ve stayed stable since 2019 thanks to joint student, faculty, and staff campaigns.* Scholarships and financial aid often come with onerous restrictions, such as that students enroll full-time–a requirement that can be impossible for the many enrolled students who work one or multiple jobs. Charging tuition also changes the incentives of administrators, who become focused on enrollment numbers at the detriment of making more holistic decisions for the good of students, and depending on tuition for revenue deepens inequalities between campuses, as some count a greater share of tuition-assisted students than others.

“There’s this sense that we need to be packing our classrooms to the gills, because we’re so reliant on tuition dollars and butts-in-seats,” Schiller said. “Even if the pedagogical mission is better served by our classes being small, that’s seemingly unimportant.… The lens of seeing students through tuition dollars treats them as customers.”

A bright spot for advocates is that after several years of isolation—during which mobilization around CUNY funding died down—students, union members, and alumni are once again assembling on the steps of the Capitol in Albany and at City Hall in New York to make their voices heard to elected officials. At a rally in May at City Hall Park with hundreds present, students toted signs that read, “No Cuts to CUNY,” “Invest in CUNY,” and “CUNY is About Racial and Economic Justice.”

Kathleen Offenholley, a professor of mathematics at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, said at the rally that nine of her students had come along with her. They were excited about the idea of a free CUNY for everybody as “deeply important anti-racist work,” she shared. Schiller noted that in the course of advising her students that day, she had heard from two students for the first time that they wanted to get involved in the fight to fund CUNY. “It’s been years since any student has said that to me,” she said.

* This article originally misstated the amount that tuition had risen.