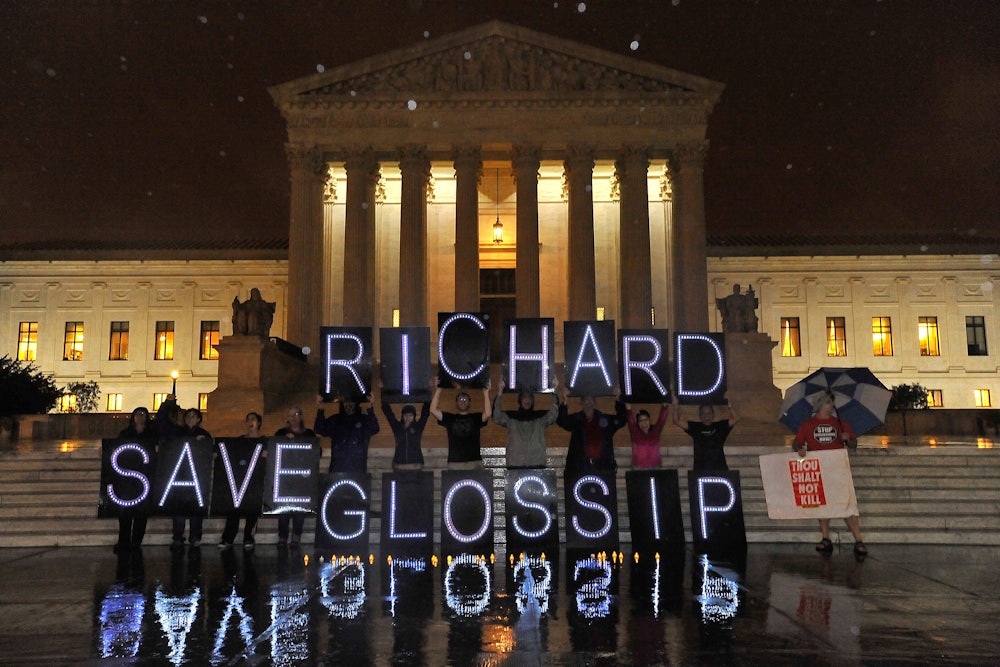

The state of Oklahoma is trying to execute Richard Glossip. It has tried to execute him for the last quarter century. Oklahoma prosecutors charged Glossip with the murder of a motel owner in Oklahoma City in 1997 and persuaded a jury to convict him of the crime and sentence him to death for it. Oklahoma’s lawyers have fought each of his post-conviction appeals on a variety of grounds, including the fairness of his trial and the method of his planned execution. His execution is scheduled for May 18.

The state of Oklahoma is also trying to not execute Richard Glossip. Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond took the extraordinary step last month of asking state courts to halt Glossip’s scheduled execution, citing new evidence that undermines the credibility of his original conviction. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals rejected that request, however, and now Drummond is begging the Supreme Court to intervene.

“Absent this court’s intervention, an execution will move forward under circumstances where the Attorney General has already confessed error—a result that would be unthinkable,” the state told the justices in a brief filed on Monday. “In those unprecedented circumstances, this Court should grant the application for a stay of execution.”

Glossip’s case reads like a road map of the many flaws that afflict American capital punishment. His plight is both ordinary and extraordinary. Here is a man who is probably innocent of the crimes for which he was charged, allegedly railroaded onto death row by subpar lawyering, lazy policing, and judicial indifference. There is no magic DNA test or eleventh-hour confession by another perpetrator, no dramatic last-minute reveal like some mid-tier Law & Order episode. There is only an imminent failure by a system that values finality over innocence.

The saga began on the night of January 7, 1997, at which time Glossip worked as the manager of a motel in Oklahoma City. Justin Sneed, the motel’s 19-year-old maintenance man, broke into a room and attacked motel owner Barry Van Treese with a baseball bat. After a brief scuffle, Sneed used the bat to bludgeon Van Treese to death. Sneed then stole cash from Van Treese’s car, hid the car and his blood-soaked clothing in a nearby parking lot, and fled the area. Police discovered Van Treese’s body the next night and later apprehended Sneed.

The Intercept’s Liliana Segura and Jordan Smith, who have covered the case and early investigative missteps over the last decade, reported last year that the early police investigation was shoddy at best. Numerous witnesses weren’t interviewed at the time. Leads went unpursued. According to their findings, detectives quickly grew suspicious of Glossip and his potential role in the murder after he supposedly failed to disclose information to them. Glossip had run into Sneed a few hours after the murder and asked about his black eye, to which Sneed “flippantly” replied that he had just killed Van Treese. Glossip did not believe him until later in the following day, apparently chalking it up as a bad joke about his boss, and didn’t tell the police immediately.

That suspicion was the foundation on which police built a narrative in which Glossip was really the mastermind of Van Treese’s murder and Sneed, the actual perpetrator, was merely carrying it out at his behest. According to Segura and Smith, investigators tried to get Sneed to say that Glossip had manipulated him into carrying out the murder before questioning him about his version of events. Glossip’s lawyers, for some inexplicable reason, never showed the jury the videotaped interrogation where Sneed is cajoled into pinning ultimate blame for the murder on Glossip.

How could Glossip be charged for a murder he didn’t commit? Under the felony-murder rule, when someone is murdered during the course of another crime, any co-conspirators in the underlying crime can be charged with murder in addition to the person who actually does the deed. Imagine that a group of robbers break into a bank and one of the burglars shoots and kills a security guard during the robbery. The felony-murder rule generally allows prosecutors to charge all of the robbers with murder.

This rule has been widely criticized in recent years on multiple grounds. One of the main reasons is that it creates perverse incentives in the criminal justice system: The defendant who actually committed the murder can agree to cooperate with prosecutors in exchange for a lighter sentence by testifying against his colleagues for his crime. That’s exactly what happened in Glossip’s case. Sneed, who allegedly had a history of stealing from motel guests to fuel his methamphetamine addiction, testified that he was under Glossip’s control and influence when murdering Van Treese. Sneed was sentenced to life without parole. Glossip was sentenced to death.

Glossip’s plight did not receive wider attention until 2015, when by sheer happenstance he became the named plaintiff in the Supreme Court case Glossip v. Gross. He and other death-row inmates in Oklahoma sued the Department of Corrections to stop the state from using the drug midazolam to execute them. Oklahoma and other states had turned to the untested sedative after a European Union embargo cut them off from access to the most commonly used lethal injection drugs. After a series of botched executions involving midazolam, including two in Oklahoma where the condemned men writhed in agony as they died, the court agreed to hear the prisoners’ challenge.

It did not end well for them. At oral arguments, Justice Samuel Alito asked why the court should accept “what amounts to a guerilla war against the death penalty” and effectively reward death penalty abolitionists for cutting off drug supplies. His majority opinion set an extraordinarily high threshold for future prisoners to challenge the constitutionality of an execution method to prevent future attempts. Alito was openly disdainful of claims and evidence that because midazolam can be ineffective, prisoners would feel like they were being immolated from the inside out as they died. “After all, while most humans wish to die a painless death, many do not have that good fortune,” he wrote.

But Glossip’s loss in that case brought renewed attention to the facts behind his original sentence. Reporters were naturally curious about the alleged crimes of the man who was consigned to a potentially excruciating death by a 5–4 vote. Segura and Smith uncovered witnesses who weren’t interviewed, missteps by defense lawyers that might have helped Glossip’s case, and other troubling flaws in the trial. They reported last year, for example, that Sneed often asked his lawyer whether he would have the opportunity to recant his testimony later in life. Sneed’s lawyer told him to say nothing.

I want to stress two things about Glossip’s troubling case. One is that if Glossip is not executed, it will only be because he was spared by the conscience and hesitation of Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond. The system otherwise worked perfectly, in a manner of speaking. Glossip was convicted by 12 fellow Oklahomans, found to be eligible for the death penalty by the court, and duly sentenced to die by lethal injection. Including his most recent effort, he has sought post-conviction relief from the Oklahoma state courts five separate times for various flaws in his trial. The courts turned him down each time.

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals’ 25-page ruling last month sounded almost exhausted by Drummond and Glossip’s joint request. It treated the petition as a minor procedural speed bump between Glossip and the death chamber, dismissing the notes about Sneed’s psychological conditions that prosecutors had previously withheld from the defense as immaterial to the case’s outcome. And that was with the state’s highest law officer backing him, a rare privilege that not every defendant enjoys. This is because the criminal justice system is structured not to prevent the execution of potentially innocent people but to execute people who have been sentenced to death. A casual reader might have expected the opinion’s final line to be: “Just get it over with.”

The second and final point worth stressing is that the Supreme Court may not actually intervene to save Glossip. As I’ve noted before, the court’s conservative majority is all but openly hostile to capital defense lawyers and contemptuous of their claims. Alito’s comments about a “guerrilla war” against the death penalty may reflect a broader desire to protect executions from the meddling of activists, abolitionists, and desperate defense lawyers. This is largely the same court that went out of its way to ensure that a prisoner would be executed despite lodging a strong religious freedom challenge to how his execution would be carried out a few years ago, leading to a palpable rift among the justices over that case’s outcome.

It would be shocking if the Supreme Court rejected Glossip’s petition. I would like to think that the justices’ desire to see executions go forward over the wishes of death penalty opponents does not apply when the state itself is one of the opponents. But it would not be surprising if the court lets things go forward. What was once described as the “machinery of death” is slow but relentless, and it will continue to grind out cases like Glossip’s as long as the American people let it.