The last time Eduardo saw his best friend, Kesley Vial, a 23-year-old asylum seeker from Brazil, Vial was unconscious. He had been found hanging from a shelf in his cell at the Torrance County Detention Facility, a sheet tied around his neck. Seven days later, at a hospital in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Vial died.

Eduardo, who is from Ecuador and was also being held at Torrance, a private Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center about an hour southwest of Albuquerque, was already depressed. But Vial’s death pushed him into a crisis that’s still difficult to talk about. Kesley “was a joyous person, a good person. He danced that morning. He danced almost every day,” said Eduardo, who asked to go by a pseudonym for safety. “But being locked up in there is hell.”

After Vial’s death, Eduardo attempted suicide himself. For at least two straight months, he reported having suicidal thoughts nearly every week. He was released from Torrance in December, once the detention center’s medical unit finally diagnosed him with suicidal ideation, said Sophia Genovese, supervising attorney at the New Mexico Immigrant Law Center, a pro bono legal group that works with asylum seekers locked up in the state’s detention centers. In total, Eduardo was held at Torrance for nearly eight months.

That Torrance pushed Vial and Eduardo to such mental anguish does not surprise immigrant-justice advocates. In 2021, the facility, which is operated by the corporation CoreCivic, failed a government inspection performed by the third-party contractor Nakamoto Group. The inspection cited dangerous understaffing and squalid living conditions, including inedible food. Last year, the Homeland Security Department Office of Inspector General twice recommended Torrance’s closure. And in a September report, it noted concerns with the facility’s inadequate medical care. (ICE disputed the findings, and refused to respond to my repeated requests for comment.)

Torrance “exemplifies everything that is wrong with immigration detention and why the detention system must be abolished in its entirety,” said Luis Suarez, field advocacy manager at Detention Watch Network, in a statement. According to Genovese, by late December 2022, the number of people held at Torrance had gone down to just a handful.

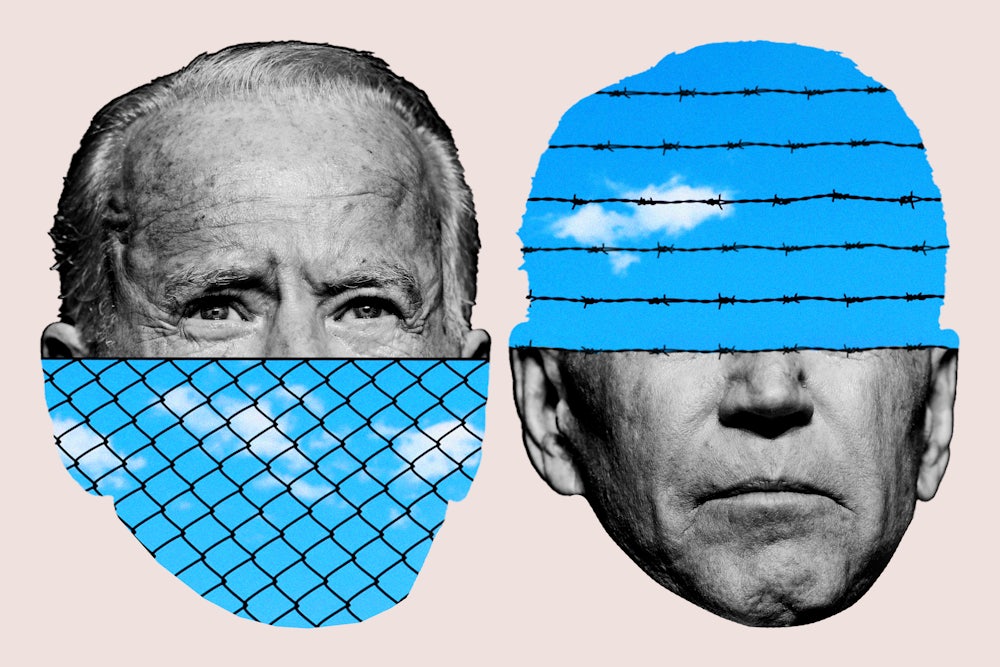

President Joe Biden once promised to phase out the use of private immigration detention centers. But his government continues to jail asylum seekers, and in March reports emerged that the administration was considering detaining asylum-seeking families apprehended along the U.S.-Mexico border, after largely stopping the practice over the last two years. Biden’s proposed budget for 2024 includes nearly $25 billion for ICE and Customs and Border Protection, an $800 million increase in funding compared to 2023. For all his claims to the contrary, Biden has built on Donald Trump’s legacy of intensified crackdowns on asylum seekers and ignored mounting evidence of the physical and mental harms—including death—triggered by detention. Between January 2021 and the first quarter of 2023, at least eight people died in ICE custody.

In fact, the Biden administration is not simply “willing to stand by and allow torture to take place”—it’s actually facilitating it, said Ariel Prado, co-director of Innovation Law Lab’s Anticarceral Legal Organizing program. Immigrants are being maltreated in places that aren’t “fit to hold any human beings, in order to cause fear.” In late December, ignoring the plentiful warnings about conditions at Torrance, the administration began transferring hundreds of immigrants into the facility.

Eduardo’s friend Vial, who was apprehended in El Paso, Texas, arrived at Torrance back in April 2022. He failed his “credible fear” interview, the initial screening that determines whether a person can apply for asylum in the United States, and in June an immigration judge ordered his deportation. The next month, Vial was transferred to a facility in Florence, Arizona, to prepare him for his removal to Brazil. But instead he was brought back to Torrance, according to ICE’s death review report. During mental health evaluations, he repeatedly said he was suffering from depression, anxiety, and insomnia, and explained that he was extremely frustrated by the lack of information he was receiving from ICE about his case.

One August morning, an ICE official told Vial that his deportation had been delayed again, this time until the beginning of September. Early that afternoon, he hit a wall with his hand and sat on the ground, crying, according to ICE’s death report. He was sent to another mental health evaluation. About 30 minutes later, he returned to his cell. He was found unresponsive later that afternoon, when officers entered his housing unit for count.

Advocates blame Torrance’s inhumane and abusive conditions for Vial’s death. The death report, said Ian Philabaum, co-director of Innovation Law Lab’s Anticarceral Legal Organizing program, “is the watered-down version of a young man crying out for help and receiving poor services while he’s being mistreated in this facility.” It’s also the end of the story for ICE and CoreCivic, which “get to wash their hands off it and continue modus operandi.”

Following Vial’s death, some of his fellow detainees went on a hunger strike, but the protest was broken up after about two weeks. ICE quickly deported most of the people involved, and advocates say conditions at Torrance—including serious due-process violations—have only gotten worse in the months since. There have also been several more suicide attempts, according to Innovation Law Lab, including, in November, that of Rafael Oliveira do Nascimento, an asylum seeker from Brazil.

Other asylum seekers formerly held at Torrance—along with people from Otero County Processing Center in Chaparral, less than half an hour north of El Paso, Texas, and Cibola County Correctional Center in Milan, about an hour west of Albuquerque—described similar stories of psychological abuse, prolonged detention, threats and retaliation from guards, due-process violations, and a sham and unfair immigration process that leads to wrongful deportations. There’s also wide documentation of severe medical neglect, poor or nonexistent mental health care, inedible food, chronic sleep deprivation, and other conditions that rapidly deteriorate the well-being of asylum seekers and immigrants detained at the three facilities.

Cristian, a Venezuelan asylum seeker using a pseudonym because he fears retaliation, said he was placed in solitary confinement for 15 days at the Otero facility, which is operated by the Management and Training Corporation, after he accepted a note from one of the kitchen staff members. Cristian’s stay in “el hueco”—the hole, as many detainees refer to it—is just one example of what advocates and lawyers have long denounced as an excessive and arbitrary use of solitary confinement inside ICE detention centers in New Mexico and nationwide. (CoreCivic and MTC deny allegations of abuse and inhumane conditions at Torrance, Cibola, and Otero.)

“This damages your mind,” Cristian told me from a Telmate phone call inside Otero in mid-February. At the time, he had been detained there for nearly six months, despite passing his credible fear interview, having a sponsor in the United States, and being granted relief by an immigration judge under the Convention Against Torture, according to his attorney, Zoe Bowman, of the El Paso–based Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center. “Do you know what it’s like to be in a hole, alone, for 15 days without speaking to a single person? This is not human.”

Eduardo and Cristian were among the more than 6,200 asylum seekers and immigrants whose confidential information was neglectfully published on ICE’s website last November. The data leak included their names, birth dates, nationalities, detention locations, and the status of their asylum cases. As a result of the massive leak, ICE released nearly 3,000 people in January. Cristian was finally let out in late March.

Solitary confinement is also used at the facilities to isolate people who say they’re experiencing a mental health crisis, including thoughts of suicide and self-harm. A February report by Innovation Law Lab recounted the plight faced by those who are sent to “los cuartos de tortura,” or torture rooms, as they’re often called, at Torrance. Eduardo was placed in these rooms numerous times. His clothes were taken away and replaced by a thin hospital smock. The lights were on constantly, the vents blasted cold air, and for all three meals he was served raw carrots, bread, and water. He slept on the pavement floor. Such conditions force many detainees to claim that their suicidal thoughts have passed just so they’ll be let out. In a statement to The New Republic, CoreCivic referred to the Innovation Law Lab report as “sensationalized.”

Even under these distressing circumstances, asylum seekers still find ways to resist. David, who’s from Venezuela and also asked to go by a pseudonym, said he joined two hunger strikes last November and December while detained at Otero. “This was our only tool to make our voices heard,” he explained. He knew of other hunger strikes at the facility, sometimes carried out by only one person. Often, he said, officials responded with threats of force-feeding the strikers. One man was taken to solitary to pressure him to end his hunger strike. In December, following a second collective hunger strike, David said an asylum seeker from the Dominican Republic attempted suicide at Otero out of frustration that nothing was getting better.

David’s information was part of ICE’s data leak last year, and after he was released on parole, he finally reunited with his pregnant wife. “Their purpose is to instill fear in you, to abuse you psychologically so that you’ll voluntarily ask for your deportation,” David said. “I think that’s one of the main objectives of why Otero is so brutal, so that we’ll ask to be deported.”

Medical neglect is rampant at the three facilities. When Carlos, a Colombian asylum seeker, arrived at Cibola, he had broken ribs from being robbed and assaulted in Mexico. Besides acetaminophen, he said, he never received care. At Otero, David said, detainees were given handfuls of pills of different colors and told to take them without explanation of what the medication was actually for. The same has been reported at Torrance, where many say they’re overmedicated with unidentified pills. Others don’t receive the medication needed to treat their chronic health conditions.

While Biden’s government has disregarded reports of these abuses, advocates continue to apply local pressure, with the aim of one day shuttering the facilities. In January, a bill introduced in New Mexico was part of a nationwide wave of similar measures seeking to ban contracts between ICE and state and local governments. Legislation has been proposed or enacted in at least eight other states, including California, Oregon, New Jersey, and New York. And the movement scored a massive victory earlier this year, when, after nearly a decade of grassroots advocacy, mounting pressure from activists led to the closure of ICE’s troubled Berks County Residential Center in Pennsylvania.

In March, the New Mexico bill was ultimately voted down by the state Senate; its opponents successfully persuaded even some Democrats in the legislature to vote against it, arguing that ending immigrant detention would be bad for local economies. Advocates counter that detention centers are not, in Genovese’s words, “profitable or beneficial” to the rural communities where they are frequently located. “We are working to fight now at the federal level to cancel these individual contracts one by one,” she said.

As Eduardo attempts to recover from the trauma of his detention, he continues to fight for asylum in the United States. He remembered an ICE agent who oversaw immigration cases at Torrance who would often tell those detained that the only way they’d be released would be if they died. There were moments, Eduardo said, that he truly believed that. Today, he lives with his brother on the East Coast. “These places should not exist,” he told me. “They are torture.”