In the early 1970s, two Washington Post reporters investigated the arrest of seven would-be burglars who attempted to break into the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. With the help of the evocatively named “Deep Throat” and other unnamed sources, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein helped uncover a scandal that led to the first resignation of a president of the United States.

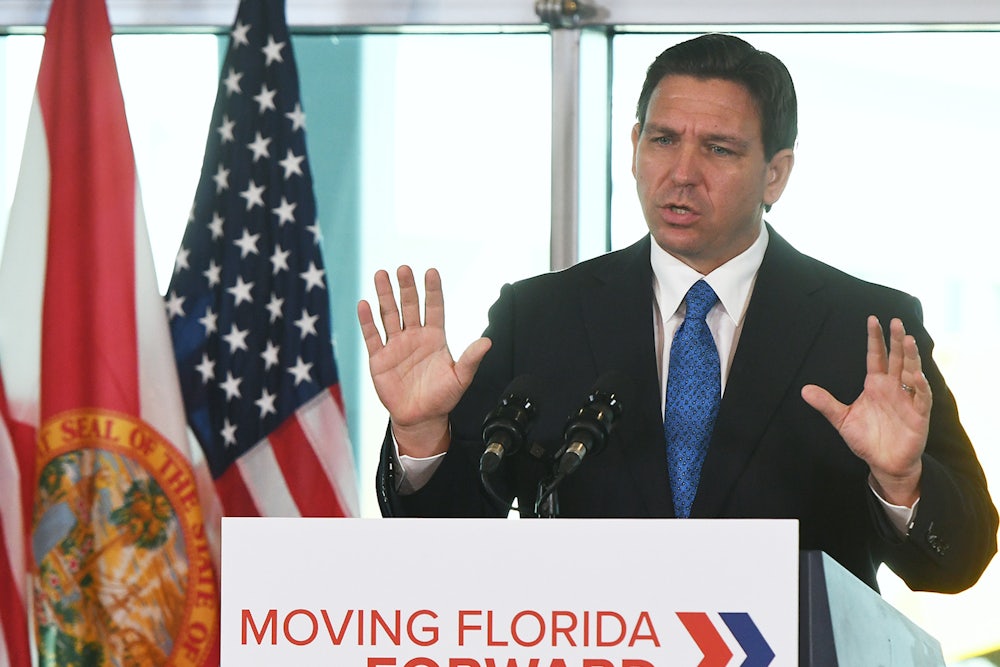

In Ron DeSantis’s Florida, however, Richard Nixon might have simply sued Woodward and Bernstein into penury. A bill introduced last month by a Republican state lawmaker in Tallahassee, which DeSantis supports, would rewrite the state’s defamation laws to make it easier for would-be litigants to bring successful claims against news outlets in court. It would effectively ban anonymous sources and allow public figures to punish people who accuse them of racism, sexism, or homophobia. As The Washington Post reported on Thursday, the bill would be a severe blow to journalism in the Sunshine State—and, perhaps, a tactical misjudgment by its backers, as conservative media might be the most likely target if defamation suits proliferate.

Much of the bill tackles the “actual malice” standard, which sets a high threshold for defamation claims in the U.S.: To prevail under that standard, a plaintiff must typically show that the publisher of the material in question knew that it was false when they published it or showed a “reckless disregard” for whether it was true or false. It’s not generally enough for the statement to simply be wrong or for the error to be inadvertent. Something more reckless or malicious, so to speak, is typically required.

The Florida bill does not propose to scrap the standard outright, which is beyond the state legislature’s power. (More on that later.) Instead, it tries to carve exceptions that could undermine the standard’s purpose. One provision, for example, would establish that plaintiffs don’t need to meet the actual malice standard “when the allegation does not relate to the reason for his or her public status,” which would make it riskier to conduct reporting about elected officials and other public figures.

One part of the bill would make it easier for would-be litigants to sue people who accuse them of discrimination. The bill stated that any allegation that someone “has discriminated against another person or group because of their race, sex, sexual orientation, or gender identity” is considered inherently defamatory. It goes on to add that defendants can’t cite a plaintiff’s “constitutionally protected religious expression or beliefs” or their “scientific beliefs” if it involves sexual orientation or gender identity. In practice, this could mean that someone who describes a Florida politician’s bill as discriminatory towards LGBT Floridians could be sued for it, and the defendant couldn’t cite the politician’s own beliefs as a defense.

Another ominous provision in the Florida bill targets the use of anonymous sources. Some states have statutory or constitutional protections for reporters that would prevent them from disclosing their sources in court. Under the proposed bill, Florida would go in the opposite direction. It would declare that any statement attributed to an anonymous source would be “presumptively false for purposes of a defamation action,” and in cases where a reporter refused to give up their source, the legal standard for the plaintiff to win would be lowered to negligence.

If the bill is enacted, reporters would be compelled to give up their anonymous sources—and thus break a cardinal rule of journalism and permanently damage their careers—or face severe legal penalties. Making it legally untenable to use anonymous sources would also make it that much harder to hold corrupt and malevolent public figures accountable for their actions. Sources will be less likely to come forward if they know they face the risk of retaliation for speaking up.

This would be a major shift from the status quo. Thanks to the actual malice standard, it is extraordinarily hard for public figures to win a defamation case in the U.S. (Separate standards exist for private figures, and private figures can occasionally become public figures in some instances.)

This actual malice standard dates back to the Supreme Court’s ruling in New York Times Company v. Sullivan in 1964. In Sullivan, the court overturned a defamation claim brought by the police commissioner of Montgomery, Alabama, against the newspaper for publishing an ad purchased by civil rights activists that described their experiences at the hands of police officers in Montgomery. Though the ad did not mention Sullivan by name, he nonetheless brought a defamation case against the newspaper and won in Alabama state courts. The Supreme Court overturned those judgments and set a higher threshold on First Amendment grounds.

Many of the Florida bill’s provisions would therefore appear to be unconstitutional under Sullivan and its successor cases. But that may be exactly the point. “There is a strong argument to be made that the Supreme Court overreached,” Florida Representative Alex Andrade, the bill’s author, told Politico in an interview last month, referring to the Sullivan decision. “This is not the government shutting down free speech. This is a private cause of action.”

Two justices on the Supreme Court have already expressed a willingness to “revisit” or overturn Sullivan if given the opportunity. In 2019, the court declined to hear a case involving disgraced comedian Bill Cosby and Kathrine McKee, who had unsuccessfully sued Cosby for defamation over claims he made in a letter after she publicly alleged that he had raped her in the 1970s. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in a separate opinion that while the court had correctly declined to hear the case for procedural reasons, it should take the opportunity to revisit Sullivan on originalism grounds.

“We should not continue to reflexively apply this policy-driven approach to the Constitution,” he suggested. “Instead, we should carefully examine the original meaning of the First and Fourteenth Amendments. If the Constitution does not require public figures to satisfy an actual-malice standard in state-law defamation suits, then neither should we.”

Two years later, Justice Neil Gorsuch expressed a similar interest in rethinking Sullivan if an appropriate case comes before the court. “Rules intended to ensure a robust debate over actions taken by high public officials carrying out the public’s business increasingly seem to leave even ordinary Americans without recourse for grievous defamation,” he wrote in a dissent from the court’s refusal to hear a defamation case in 2021. “At least as they are applied today, it’s far from obvious whether Sullivan’s rules do more to encourage people of goodwill to engage in democratic self-governance or discourage them from risking even the slightest step toward public life.”

Thanks to Sullivan, the U.S. is something of an outlier in this area of law. Plaintiffs in other liberal democracies generally face fewer obstacles when bringing defamation cases before a court. But their experiences also show the hazards of setting the threshold for defamation claims too low. British defamation law, for example, is notoriously favorable toward plaintiffs, who themselves already tend to already be the wealthiest and most powerful citizens. Instead of encouraging media responsibility, Britain’s approach has also created a relentlessly invasive tabloid media culture that resulted in a phone-hacking scandal about a decade ago. Congress even took the unusual step of forbidding American courts from enforcing British libel judgments in 2010.

The threat of litigation in countries without America’s high level of press protection can have a subtle but profound chilling effect on journalism and accountability. Australian legal commentators, for example, noted that the #MeToo movement faltered in that country after figures like actor Geoffrey Rush began suing the women who accused them of sexual misconduct under Australia’s strict defamation laws. British human rights lawyers have warned that Russian oligarchs have used British defamation laws to suppress reporting about their activities in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year.

It is thus unsurprising that the leading figure in the public crusade against American defamation laws is Donald Trump. He has never been shy about his reasons: to prevent news outlets from publishing harmful coverage of him. “We’re going to open up those libel laws,” he told supporters on the campaign trail in 2016. “So when The New York Times writes a hit piece, which is a total disgrace, or when The Washington Post, which is there for other reasons, writes a hit piece, we can sue them and win money instead of having no chance of winning because they’re totally protected.”

Ironically, that should give Florida lawmakers some pause before “opening up” their own libel laws. The most perilous set of defamation lawsuits against a media organization in recent years wasn’t brought against the Times, the Post, or any other mainstream news outlets. That dubious distinction instead goes to Fox News, which is facing multibillion-dollar claims by voting machine companies for its misleading coverage of the 2020 election. Evidence obtained by the plaintiffs during the discovery phase of litigation appears to show that Fox News hosts gave platforms to less-than-credible figures while producers and executives knew the voter fraud claims were false, and that some of the channel’s top figures sought to prevent Fox reporters from fact-checking those assertions.

If anything, lowering the threshold for defamation lawsuits could be more dangerous for the conservative media ecosystem—which, among other things, often accuses its perceived opponents of “grooming” young children—than it would be for anyone else. Fox is not the only outlet to be hit with defamation lawsuits for its election fraud claims; similar litigation is underway against Newsmax, a Fox competitor on its right flank, and they were hardly the only two outlets on the right that peddled falsehoods about the 2020 election.

The Post on Thursday quoted James Schwartzel, the owner of a major talk-radio station in the state, describing the bill as “the death of conservative talk throughout the state of Florida.” It could also be risky for Trump himself, a recent Florida émigré whose record of making unproven claims is well established. The former president recently posted that his 2024 rival, “Ron DeSanctimonious,” was “grooming high school girls with alcohol” while working as a teacher. He offered no evidence to support those allegations beyond a photograph of DeSantis standing alongside young girls.

A high threshold for defamation cases is a public good. It protects not only press freedom but free speech in general from bad-faith adversaries. It helps ensure that Americans are not pursued by the wealthy and well-connected for criticizing them and accusing them of wrongdoing. A robust standard ensures that cases won’t be decided by whichever side can pay its lawyers the longest. And it does not enable genuine misconduct by media organizations, as Fox’s legal woes may soon demonstrate. It’s up to Florida lawmakers to decide whether the risk here is truly worth it.