Not long ago, I wrote that liberals had a heaven-sent opportunity to push back against the ultraright, ultraactivist supermajority on the Supreme Court by coalescing behind legislation to end Supreme Court justices’ anomalous status as the only federal judges who are not subject to an ethical code of conduct. Campaigning to plug that loophole, I stressed, would have broad bipartisan appeal, could spotlight the justices’ zest for de facto repeal of legal safeguards prized by everyday Americans, and could induce at least some of those justices to tamp down their reactionary activism.

The problem was that on Capitol Hill, Supreme Court code of conduct legislation was not going anywhere. Democrats favored gaudier institutional makeover reforms such as court expansion and term limits; Republicans, meanwhile, perceived Supreme Court ethics reform as a thinly veiled partisan attack on their conservative appointees. But two weeks after those words appeared on these pages, my bleak assessment turned out to be wrong. Supreme Court ethics reform has legs—and with influential people within the Democratic Party and liberal court-watching circles starting to cotton on to the idea, it’s time to strike while the iron is heating up.

On February 9, Senate Judiciary Committee Chair and Majority Whip Dick Durbin announced himself an enthusiastic original co-sponsor of the 2023 version of the Supreme Court code of conduct bill that Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy and Georgia Representative Hank Johnson had co-sponsored in previous Congresses.* That same day, CNN Senior Supreme Court Analyst Joan Biskupic, drawing on her sources inside the Court, reported that the justices, feeling the heat, had revived their discussions about adopting a code of conduct on their own.

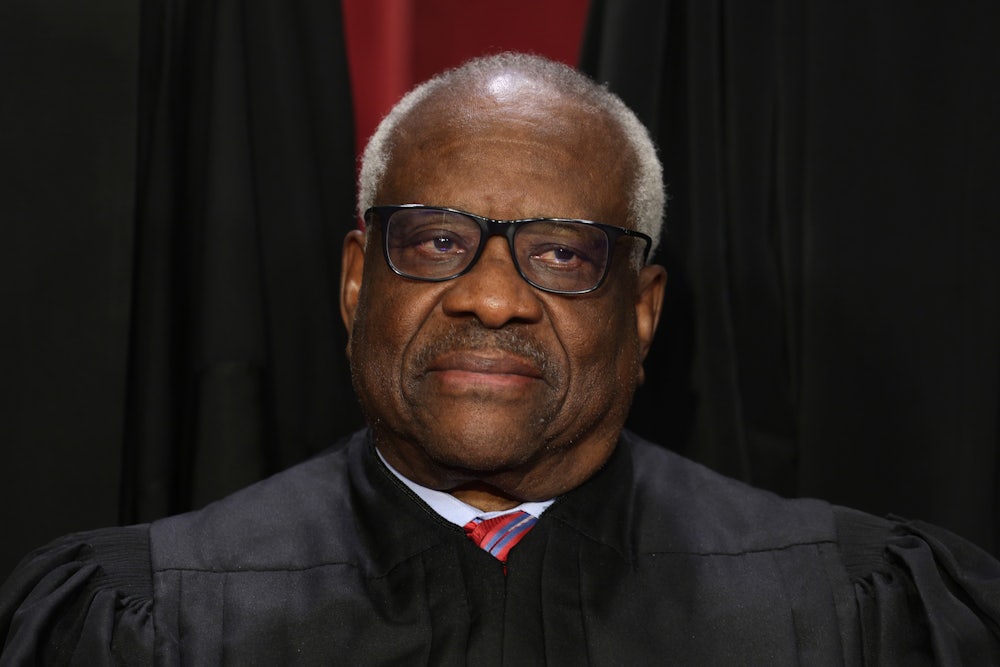

But as The Washington Post subsequently reported, those discussions had foundered, in all likelihood because Justices Clarence Thomas and (probably) Samuel Alito weren’t receptive to the idea (and because Chief Justice John Roberts and his allies lack the political will to second-guess colleagues on their ethics judgments—as Roberts has publicly acknowledged).

This wasn’t a completely bad sign, however. The Post’s revelation appeared in an extensive recap of the history of efforts, on both sides of the aisle, to enact code of conduct legislation for the Supreme Court. The fact that top mainstream media had assigned their experts thus to dig deep into this issue signaled that Supreme Court ethics reform had, at least, caromed toward the center of their radar screens. It wasn’t long before the idea popped up on the action agendas of progressive Supreme Court pundits and activists who, previously, had been laser-focused exclusively on court-packing or term limits. In mid-February, The Nation’s Elie Mystal wrote that “imposing ethics rules on the Supreme Court … is maybe the first step in rebalancing the distribution of power among the branches of government.” Days later, Demand Justice’s co-founder and chief counsel (and former Obama White House associate counsel), Chris Kang, endorsed code of conduct legislation as a “first step” toward rebalancing interbranch power, and comparatively “low-hanging fruit” ripe for plucking.

Kang also recognized that campaigning for ethics reform could be an ideal messaging platform for Senate Democrats—perhaps to hold serial hearings parading victims and experts to “shine a light” on the myriad ways in which “the Court is not looking out for everyday Americans.” He also stressed that this readily marketable issue represents a chance for liberal politicians to get over their entrenched “broader reluctance” to take on the Court “as a political branch.” Demand Justice’s website continues to list enlarging the Court to 13 justices and limiting justices’ terms to 18 years as its top two reform proposals. But ethics reform is now listed as number three—and Kang’s labeling code of conduct legislation a first step appears to recognize it as the current priority target for liberal Supreme Court reform.

In short: The idea of ethics reform for the high court has penetrated the zeitgeist. So what are the next steps? For Congress’s incipient consideration of Supreme Court ethics legislation, calling out the vacuousness of Roberts’s and his allies’ constitutional defense is a crucial first step. Roberts et al. insist that preserving their unique immunity from binding ethics guardrails is necessitated by the constitutional principle of “separation of powers.”

Ethics reform legislators and advocates should have no trouble exposing this claim as a sham. As American University judicial ethics expert Amanda Frost testified to the Senate Judiciary Committee in May 2022, while legitimate separation of powers principles deny Congress “power to control federal judges’ decisions or penalize Article III judges for judicial outcomes it dislikes, regulating judges’ and justices’ ethical conduct does not undermine the federal courts’ decisional independence.” (Emphasis added.) “To the contrary,” Frost observed, ethics legislation promotes separation of powers principles, by “bolster[ing] the power and prestige of the third branch, enabling it to fulfill its constitutional role as a check on the political branches.”

Lower court federal judges, who have been covered by a mandatory code of conduct for decades, have encountered no adverse impact on their ability to render independent decisions. Finally, the long history of judicial ethics laws also undermines the current justices’ contention that new restrictions could unconstitutionally invade the court’s independence. As I and others have written, statutory ethics provisions applicable to the Court were enacted as long ago as 1792, and as recently as April 2022.

Duly marginalizing the justices’ separation of powers defense is especially important, because of new strengthening provisions that Senators Murphy and Durbin and Representative Johnson have added to the 2023 version of their bill. Like previous Supreme Court code of conduct bills, this year’s iteration requires the Judicial Conference of the United States, headed by the chief justice but composed primarily of lower-court federal judges, to promulgate a code of conduct for the entire federal judiciary, including the Supreme Court, while authorizing provisions “applicable only to certain categories of judges or justices.” (Bill sponsors added this proviso to moot Roberts’s contention that his court presents some unique ethics issues different from those faced by lower court judges.)

But two new components add considerable heft. Hammering home the constitutional foundation for Supreme Court ethics laws could strengthen the prospects that these provisions stay in the bill and, in turn, strengthen the prospects that they could, if enacted, be upheld—ultimately, by the Supreme Court itself.

The first new provision creates for the Supreme Court the equivalent of the inspector general office created by the Carter-era statute to reform executive agencies. The bill directs the Court to appoint an Ethics Investigation Counsel, “who shall adopt rules [for] enforcement of the code of conduct,” including a “process” to receive public information about potential violations of the code. The counsel “shall [among other things] conduct investigations into potential violations [of the code].” The counsel is given a four-year term and is removable by the court (only) “for cause”—a term which, historically, has set a very high bar to termination.

The bill spells out no enforcement or remedial mechanism to be applied either by the court or the counsel. But it does require the counsel to issue an annual report detailing “steps taken” in response to public complaints. Hence, this provision does not subject the justices to disciplinary action by a person or institution separate from the court or outside its supervisory power. But experience with the executive branch inspectors general teaches that, in practice, at a minimum, the threat of investigations and public reports would significantly sharpen incentives for the justices (and parties to cases) to steer well clear of potential real or apparent conflicts of interest.

The second new provision in this year’s Supreme Court Ethics Act puts some teeth into a requirement long on the statute books, prescribing criteria for recusal decisions by federal judges and Supreme Court “justices.” The law, Section 455 of the federal criminal code, mandates all federal jurists to recuse from “any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned,” and, more specifically, to recuse if “the judge or the judge’s spouse … is known by the judge to have an interest that could be substantially affected by the outcome of the proceeding.”

Those criteria sound strict on paper; plainly, they would require Justice Clarence Thomas’s recusal from recent and anticipated future cases potentially implicating his wife Ginni’s involvement in promoting the overturning of the 2020 election. But in practice, this law has been close to a dead letter, at least for Supreme Court justices, because its somewhat vague prohibitions contain no enforcement mechanism.

To fill that gap, the new bill adds a section entitled “Recusal of Justices.” This provides that a justice must publicly disclose his or her rationale for recusing from a case under Section 455, and, further, must publicly disclose reasons for denying a motion by any party to a case before the Court to recuse under Section 455. Again, there is no subordination of individual justices to an external disciplinarian. But the disclosure requirements would likely incentivize individual justices to pay much more careful respect to Section 455 recusal dictates than they do now, or ever have.

These two additions materially improve on the predecessor Murphy–Johnson Supreme Court Ethics Act, and the sponsors should make every effort to retain them, at least in substance, while seeking to round up Republican supporters. To do that, they will need to discredit the chief justice’s excuse for continued immunity from universal common-sense ethics restrictions. Rolling out that (robust) case should help members of Congress shed their resistance to pushing back against this court’s high-handed usurpation of Congress’s constitutional role, and to insisting that serving on the highest court in the land does not put its members above the law.

Despite the pervasive polarization which, inevitably, colors debates about Supreme Court ethics, there is reason to expect that some Republican lawmakers could sign on to an effort for a meaningful code of conduct bill. As I noted in my January 26 article, in 2022, Republican Senators Lindsey Graham and John Kennedy each signed letters questioning, “[W]hat justifies the Court in having a lower disclosure standard than the other branches of government?” On the House side, in 2018, Republicans Bob Goodlatte, then chair of the House Judiciary Committee, and Darrell Issa, chair of the Judiciary’s Subcommittee on Courts, co-sponsored a code of conduct bill covering all federal jurists, including Supreme Court justices. That bill also amended Section 455 with a requirement that Supreme Court justices inform the public of any decisions to recuse “along with an explanation for such recusal”—substantially matching the similar provision in the current Murphy–Durbin–Johnson bill.

But if some or all of these new provisions cannot muster the votes to move forward, then it will be critical for Congress to enact a barer bones code of conduct bill. And if the threat of legislation induces the justices themselves, grudgingly, to adopt a code on their own, Congress should not stand down—as even some ethics reform advocates have suggested would be an acceptable outcome. If, as virtually all reformers stress, a primary goal of a Supreme Court ethics reform exercise is to energize Congress to rebalance constitutional and political relations between Article I legislators and Article III judges, then codifying that power shift is a sine qua non. Chief Justice Roberts’s “separation of powers” excuse for deflecting universally applicable ethics guardrails amounts to deliberate constitutional obfuscation. Brandishing such claptrap insults the intelligence of lawmakers and voters. Congress needs, finally, to unequivocally dash all grounds for Roberts’s and his allies’ anti-democratic contempt.

* This post originally misidentified Rep. Hank Johnson.