The email needs a response. The video call runs in the background while I complete other tasks. Forget about taking that extra loop around the block today. I’ve requested, renewed, and had to return the same library book three times without even opening it.

Jenny Odell in her new book, Saving Time: Discovering a Life Beyond the Clock, argues for a different approach. She reconsiders our entrenched, stress-inducing understanding of how hours, minutes, and seconds tick away, how those patterns arose, and how nonhuman kinds of time unfold. To anchor her meandering, interdisciplinary ideas, Odell brings us with her on a drive. Our stops include a Palo Alto shopping center and a craggy beach. “I could point to different things on this roiling tapestry and tell you everything that I remember,” Odell writes. “Maybe if we sat here long enough, and I did a good enough job, then you could really know me: who I’ve been, who I am, and who I wish to become.”

During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, Odell compared Saving Time to the jeweler’s loupe she carries on walks around her neighborhood. A gift from a friend, the loupe encourages curiosity and looking closely at what surrounds her, decentralizing the self. “He gave me the capacity to have a richer experience of where I already was,” Odell says, “and I feel like that’s what I’m trying to do.”

Melissa Rodman: Your new book, Saving Time, encourages readers to discover “a life beyond the clock.” What frustrates you about the culture, and the frameworks, that we inhabit?

Jenny Odell: My biggest gripe with them is that they’re very inhumane. Those frameworks have a really inhumane history, and they continue to be really restrictive—and sometimes cruel—in terms of how people experience their time or whether or not they feel they have control over their time.

A good example is just the common conception that everybody has 24 hours in a day. As if it doesn’t matter where you are, or who you are, or what position you occupy in a social hierarchy or at a job. That’s an idea that is harmful because it could potentially lead to someone feeling like they have a personal problem with how they handle their time and sort of taking on that guilt, rather than us collectively looking for solutions that would liberate time for everyone.

M.R.: Now it hasn’t always been like this. When did this idea that you’re talking about—“being on the clock”—originate?

J.O.: It’s kind of a long and complicated history. The important thing to point out is that both the standardization of time into things like work hours and the idea of interchangeable equal hours, and also the idea of measuring work output per unit of time, typically arose in contexts such as colonial plantations, where a small group of people in power had an incentive not only to measure the labor of other people but to try to get more out of them in less time, as well as [in] religious ideas—as you see in the Protestant work ethic—about the work being sort of morally good or your needing to have something to show for all of your time.

And then, obviously, the advent of the wage. It’s interesting to look at the U.S. in particular, and the moment in which there is a transition to wage labor and how not necessarily natural that was and how much resistance there was to the idea of selling your time. It’s something that now I think we very much take for granted.

M.R.: Your research draws on “pre-industrial cultures” and the natural world. What would your ideal rhythm for people’s lives feel like?

J.O.: Something that I took away from disability studies is the idea of “crip time.” It suggests a way of looking at time that is more accommodating to everyone, not just people with disabilities. Because we all live in bodies, and our experience as human beings doesn’t really match up with the industrial model of equal interchangeable hours, and we know that intuitively.

We’re always kind of trying to fit ourselves into these structures, and sometimes it’s really uncomfortable, and it’s more comfortable for some people than it is for others. And so, when I try to imagine my ideal, it’s kind of moving in the opposite direction from that. It’s something where we have, maybe, a more fluid understanding of time and what work is: for example, considering caretaking—and forms of work that we don’t necessarily associate as strongly with productivity—more seriously, recognizing their value.

I imagine a give and take, where collectively whoever has the time and the energy gives that, and then when, say they’re sick or something, someone comes in and helps them. It’s this kind of ongoing, hopefully equitable, back and forth.

M.R.: You’ve noted on Instagram that many readers of your last book, How to Do Nothing, responded that they would “love to do nothing, but [they] don’t have time.” What would you say to them?

J.O.: My answer now would have two parts. One is that so much of it depends on who you are, right? That’s part of why I have divided chapter two into sections, basically addressing someone who really, really doesn’t have time structurally, and then someone who feels that they don’t have any time.

For someone who doesn’t have time, I would just ask that person, “Is this a case of you really, really don’t have time?” Like you have multiple jobs, you have kids, you have financial obligations, and you have a very strict work schedule. To that person, I would say, “The fact that you don’t have time, it’s obviously not your fault. And so, maybe try to begin to see it—if you haven’t already—as part of a larger structural thing in which others are also struggling in the system.” Because you, individually in that situation, don’t have a lot of power, you would have to branch out toward others and build power collectively.

You see this in the interview I have with the administrator for the working moms’ group, where she has that insight: that it would actually be more helpful for her to find six other moms, form a group, and then each one of them would make dinner for all of the others each night of a week. That’s already a kind of thinking beyond an individual who has individual hours.

To a person who, maybe they do that interrogation, and they realize that they just have really internalized this work culture and a sense of nothing ever being enough for them—in terms of keeping up or achievements in life—that person, I think, could really benefit from just trying to zoom out a little bit and get some perspective and think about where you actually find meaning in your life. In that sort of interrogation, you might very well find that there are things that you think you need to be doing, or you need to be doing them with a certain intensity, that you don’t need to do.

M.R.: In Saving Time, you asked community organizer Niki Franco a question, and I’d love to ask you that same question, “What’s a recent example you can remember of experiencing that leisured state of mind?”

J.O.: This isn’t a recent example, but when I was teaching at Stanford—often running around, schlepping big bags around, going between classes, and kind of stressed out—I would often be interrupted by some bird on the way to class, which unfortunately would make me late. But I do remember feeling that time kind of stopped or felt very different or expanded in a way. All of my attention was collected into just observing something that could go away any second. That’s an aspect of birdwatching that I think is almost easy to overlook: What’s so captivating about a bird is that it arrives, but it could leave at any second. So you kind of have to give it your full attention.

And, obviously, the self who is looking at the bird is not necessarily an “adjunct lecturer” self. It’s like “me” sort of contains a lot of even my childhood curiosity about animals and just like wonderment, appreciation, and love. And then I go on my way. My time collapses back into how it was feeling before.

M.R.: And what is lateness anyway on that grand scale?

J.O: Yeah, I’m just on “bird time” while I’m looking at that bird. Especially if it’s migratory, then you’re just thinking about where this bird came from and where it’s going. And that’s obviously very different from the grid that you’re living in.

M.R.: You’ve mentioned that “time was on [your] mind” even before you wrote How to Do Nothing. How has your thinking about time, and your interest in time, evolved?

J.O.: My understanding of what time is—or what counts as evidence of time—has broadened a lot. I was aware of the feeling of time scarcity, and I was aware that I wanted to think about time differently. Even in How to Do Nothing, I talked about bird time and bird space, so I was already thinking about that. And there is an implicit argument in How to Do Nothing that not all time should be money. But I think at that point, I still was thinking about time more like money than I do now.

It feels more elaborate to me now. I really see any change as being a form of time or being evidence of time. It’s most obvious in an ecological sense, but even geological time and things like learning. The fact that even if you didn’t “do anything” one day, you are a different person the next day. Time feels kind of thicker to me. I feel like I’m in time with other things—living and nonliving—versus “I have a timeline, and I’m living it in this inert place that doesn’t itself inhabit time.”

M.R.: If there’s one misconception about time you’d like to dispel, what would that be?

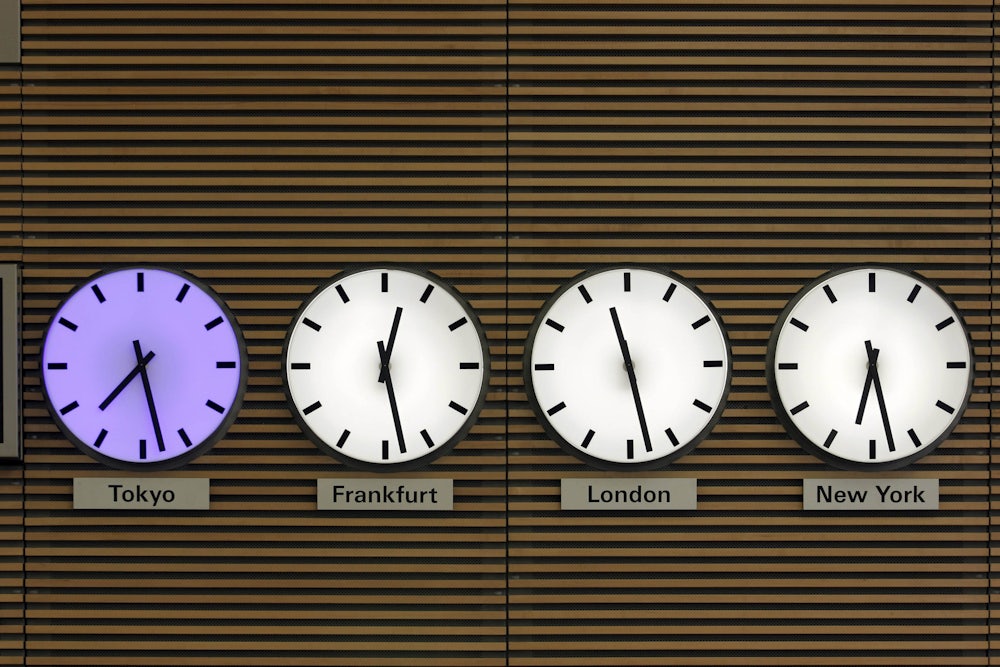

J.O.: The idea that I would push against is just that there’s something uniform about time. It’s really incredible to me how much the idea of clock-based time currently is at the root of how a lot of us, even me right now, think. It’s like a cultural instinct to think that that’s actually the nature of time, that there are these equal moments ticking away. That’s how you get this idea that everyone has hours, versus us inhabiting time together.

I also want to push against the idea that human cultural time, which I think we associate with that kind of clock time, or historical time is not the same as ecological time or geological time; that these times are kind of playing out separately. Versus seeing all of us, and all of those things, as being embedded in these very interconnected processes, which are time.

Because I think that supposed separation is one of the reasons for that very modern feeling of dissonance, where you are always running out of clock time, but you’re also aware on the margins of that, that climate time is out of joint. But you don’t really know how to square those two things, and they still feel separate.