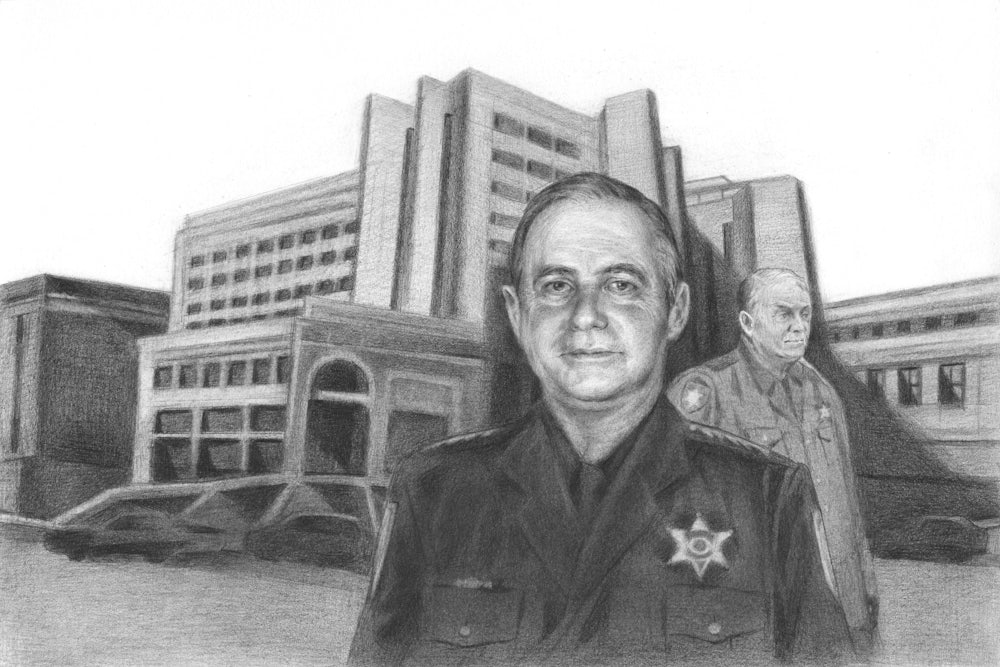

When Tim Howard, the former sheriff of Erie County in Western New York, announced his plans to retire in 2021, local organizers rejoiced. They’d spent years trying to oust him: holding weekly rallies in front of the Erie County Holding Center in downtown Buffalo every Wednesday since around 2009, supporting the campaigns of candidates for sheriff they hoped could beat Howard at the ballot box, working with members of the county legislature to compel him to answer questions at public hearings, and even calling on former Governor Andrew Cuomo to remove him from office. Thirty-two people died after being detained in jails overseen by Howard. They died in their cells or shortly after being transferred to local hospitals; most died from suicide or apparent medical neglect. Some were beaten to death by fellow inmates.

The Erie County Holding Center is the second-largest detention center in New York State outside of New York City. Despite holding far fewer inmates than Rikers, it ranks just behind Rikers in inmate-on-inmate assaults. Someone dies in an Erie County jail approximately every six months.

Information on how many people die in U.S. jails and prisons each year is spotty at best. Although the death rate in his jails was high and the suicide rate unusually so, Howard seemed to view this state of affairs as simultaneously inevitable and not his fault. As he said in 2019, “We’re not a hospital. The person most responsible for a suicide is the person that commits the suicide.” It was, in his view, “not a failure on the part of the security staff” if an incarcerated person “[chose] to use” their limited private time to kill themselves.

In spite of these well-documented miseries, and the best efforts of Erie County residents to hold him accountable, Howard remained in the sheriff’s office for 16 years and left the job voluntarily. This is partly because there is no mechanism to recall elected officials in New York, though even if there were, an effort to recall Howard might well have failed. According to the state constitution, only the governor can remove an “elective sheriff” after presenting them with “a copy of the charges against him or her and an opportunity of being heard in his or her defense”—something Cuomo showed no interest in doing.

But the larger reason for Howard’s long tenure in office is simply that sheriffs throughout the country have enormous leeway to act unilaterally, little meaningful oversight, and considerable power to enforce certain laws and ignore others. Predominantly white and conservative rural and suburban voters are crucial bases of support for county sheriffs. Right-wing groups like the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, or CSPOA, draw inspiration from what’s known as the doctrine of the lesser magistrate, a Christian theory of resistance that teaches that when a ruler becomes a tyrant he cedes any claim to legitimacy, conferring on his subordinates not just the right to resist, but the obligation to do so. The belief that sheriffs have not only the ability but a mandate to defy rulers and laws they and their supporters consider unjust makes sheriffs attractive prospects for far-right organizations.

Howard is a Republican with evident right-wing sympathies. In 2017, he spoke in uniform at a “Spirit of America” rally in downtown Buffalo, where he was photographed beneath an Oath Keepers sign amid supporters of that organization and then-President Donald Trump. Some rally attendees held flags and signs bearing Confederate and Nazi imagery. The Oath Keepers is a far-right militia group; four members were recently convicted of seditious conspiracy in the January 2021 Capitol attack. Given these optics, many saw Howard as the primary obstacle to humanely run jails. But the problem goes deeper than one man’s politics. And while some in Western New York may be ready to turn the page, it’s not at all clear that the misrule so long embodied by Howard will end under his successor.

Howard’s successor, John Garcia, was elected in 2021. Garcia spent 25 years as a Buffalo police officer before becoming sheriff. He is politically savvier and less ideologically driven than Howard. Garcia told The New Republic in a phone interview that he had been, like many Buffalo residents, “a lifelong Democrat.” In the fall of 2020, he became a Republican “because of the ‘defund the police’ movement.” Unprompted, he added that what happened to George Floyd was “murder” and what happened to “that individual in Memphis” (referring to Tyre Nichols) was a “gang assault murder.”

But, he continued, “damn if that’s going to splash on me and all the good men and women in law enforcement.” In Garcia’s view, anti-police sentiment is “stereotypical” and comparable to “implicit bias.” That’s why he couldn’t run as a Democrat, he said, even though—to his mind—the county’s distinctly Democratic lean would have made it easier to win his race as a Democrat. (Given that Republican-leaning white suburban and rural voters are crucial to winning the countywide sheriff’s race, that’s not necessarily true; Howard, a Republican, was reelected three times.)

“Ours is a noble profession,” Garcia said. “I was taught in law enforcement that the police are the people and the people are the police, but for a vocal minority to say that we’re scumbags—do we have bad actors? Yes. And what did I do when I got there? I fired three of them. And not only that but I arrested them, and that’s why.”

Despite their differences, Garcia and his predecessor are political allies and onetime colleagues. Howard endorsed Garcia in the 2021 sheriff’s race, and Garcia kept Howard on the sheriff’s office payroll as a commitments clerk for several months in early 2022. A commitments clerk typically calculates when inmates have served their sentences and can be released; Howard, who recorded more sick days than workdays at the sheriff’s office in the first month of 2022, said he worked from home and helped complete background checks on pistol-permit applicants.

Howard is white; Garcia, who was born in Spain, looks like a white man and shares Howard’s Buffalo accent. Howard relished defying his perceived enemies; Garcia is less confrontational. Asked if he thought it was appropriate for Howard to appear in uniform under an Oath Keepers sign, Garcia replied, “I can’t speak for him but I will tell you this: You’re not going to find me there. Because I’m against it 100 percent. There’s been people that have sent me mail about the election, to investigate it all, and there’s right-wing extremists and left-wing extremists and there’s no room for any kind of people that hate others or violence toward others. This is about a professional law enforcement agency. It’s a constitutional office. You’re not going to find me at any events like that, with banners or Confederate flags or whatever.”

He paused. “Now that I say that, I’ll be marching in a parade, it’ll be the 4th of July, and some idiot will have a banner. Don’t hold that against me, please.”

While Garcia is cultivating a more professional image, many in law enforcement are happy to stand with the far right. New York reportedly has more law enforcement officers who are members of the Oath Keepers than any other state in the nation. During his tenure as sheriff, Howard was also associated with the CSPOA, supporters of which have publicly claimed him as one of America’s “constitutional sheriff[s].” The CSPOA believes that sheriffs are the ultimate authority figures in their counties, “the first line of defense” in preserving citizens’ constitutional rights, and that the sheriff’s law enforcement powers “supersede those of any agent, officer, elected official or employee from any level of government when in the jurisdiction of the county.” According to them, “the power of the sheriff even supersedes the powers of the President.” (Despite his belief that he outranked the president, constitutional Sheriff Joe Arpaio of Maricopa County, Arizona, needed to be pardoned by then-President Trump after Arpaio was convicted of criminal contempt.)

Asked to characterize his relationship with the Oath Keepers, Howard was vague. “Members had approached me a number of times at rallies and thanked me for what I was doing,” he said, adding that he appreciated the group’s efforts to increase membership and bring people out “to hear what was being said at the various rallies regarding the Second Amendment … it might have been them, or maybe a different organization, that at times would come out and call out the federal government for involving themselves in something that might have been a state issue.”

Howard said that although he had attended a CSPOA meeting in Las Vegas, he didn’t agree with everything the group stood for and had refused to sign a pledge to become a member. Even so, he added, “I embraced a lot of other things that they said, and that is that wherever you are in law enforcement, the United States Constitution was our primary fundamental number one.”

In the 1997 case Printz vs. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated a section of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act that compelled local law enforcement officers to enforce the law’s background check requirements. The court ruled that Brady violated the Tenth Amendment by requiring state and local officials to perform background checks on gun buyers. The decision empowered sheriffs like Howard to flout federal and state laws they deem unconstitutional.

Throughout our conversation, Howard returned to the topic of his Second Amendment rights. Like many rural New Yorkers, he was incensed by the SAFE Act, a gun-control bill signed into law by then-Governor Cuomo in 2013. “I was the first sheriff in New York State to say, ‘I will not expend any of our sheriff’s office’s resources enforcing this law or the parts of this law that potentially would turn a law-abiding citizen into a criminal,’” he said. Later in our conversation, he complained that “as much criticism as I took from the media about [my stance on the SAFE Act], in the next breath, the media would be praising Rosa Parks for the stand that she took that resulted in the repair of what was unquestionably a social problem.”

Asked if he had any thoughts on the history of sheriffs siding with local authorities against the federal government in defense of white business owners or saw any ways in which that dynamic still existed today, Howard said he does not believe that “white privilege,” as he understands the term, exists. The real “history of conflict” in our country, he added, is not about race so much as “the haves versus the have-nots.” He acknowledged that “there may have been a time when minorities represented most of the have-nots,” but insisted he “wasn’t raised in a family that looked at minorities as being … less human than nonminorities” and maintained that, as a law enforcement officer, he’d always thought of himself as “the champion of the underdog.”

Whether or not CSPOA members and sheriffs like Howard are interpreting the Constitution correctly, it’s true as a practical matter that sheriffs have more power than the president over the people in their jails. Whatever the president believes about the rights of incarcerated people, sheriffs determine the culture of local jails. The fact that most U.S. sheriffs run their fiefdoms with minimal interference from state and federal authorities has given many of them the impression that their power is absolute and derives directly from the Constitution—and that it’s noble, democratic, and necessary to defend it.

“The sheriff is the only law enforcement executive that answers directly to the people,” Howard said. “The police chiefs answer to the superintendent; the state police answer to the governor. The town police answer to town supervisors.”

This view was reflected in Howard’s interactions with state and federal authorities throughout his tenure as sheriff. In 2009, the U.S. Department of Justice sued the sheriff’s office for a host of constitutional violations related to cruel and degrading treatment of inmates, including failure to mitigate the risk of suicide. Howard reportedly wouldn’t let federal investigators into his jails to evaluate conditions. That lawsuit was settled in 2011 on the condition that the county hires two independent experts to monitor its jails and file regular progress reports.

In 2019 and 2021, Erie County legislators questioned Howard about the possibility of deputies wearing body cameras and allegations of sexual assault in his jails. At a 2019 meeting of the county legislature’s Public Safety Committee, Howard compared those calling for deputies to wear body cameras to those who questioned the resurrection of Jesus. In 2021, New York State Attorney General Letitia James sued Howard and Erie County for failing to follow mandated procedures to address allegations of sexual misconduct between corrections officers and inmates in county jails.

When he finally stepped down as sheriff, Howard did not retire. Instead, he ran for and was elected town supervisor of Wales, a 99 percent white town in Erie County with a population of 3,000.

Howard’s departure failed to heal all wounds. Monica Lynch, a Black woman veteran with a shy, gap-toothed smile and an outspoken critic of the sheriff’s office, lost her brother to a county jail. Connell Burrell collapsed at the Erie County Holding Center in downtown Buffalo in July 2019. A slight 44-year-old man with type 2 diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Burrell had served just 12 hours of a 15-day sentence for disorderly conduct when he crumpled to the floor. He was eventually taken to Buffalo General Medical Center. A couple of days later, he was dead.

Lynch told me in 2020 that her brother was “a nice, considerate person, willing to do anything for anyone” who had acted as “more of a father figure than an uncle” to another sister’s kids: “He stepped in, played with them, took them to the bus stop, picked them up after school.” He was survived by his siblings, their children, and his 16-year-old son.

The state Commission of Correction Medical Review Board found in September 2020 that there had been, in Burrell’s case, “a gross failure by [jail] medical staff to follow agency policy and procedure for a hypoglycemic patient.” The attending nurse’s “decision to perform an unauthorized and contraindicated rescue therapy” had yielded “catastrophic results” (the nurse was ultimately fired). Had Burrell received proper care, the board concluded, “his death would have been prevented.”

“All [Howard] can say is, ‘I’m not the person that takes the inmates back and forth from the jail to the holding center … I’m not the person that’s in charge of giving them medication.… That’s on them,’” Lynch told Cloee Cooper in a 2022 phone call.

“No, it’s not on them,” Lynch responded with disgust. “You’re the top man, the top dog. Whatever your people under you do, it should fall on you, and he could care less about anybody [in his jails]. His only position is, ‘This is not a country club.’” (Or, as county attorney Cheryl Green once said of Erie’s jails, “This isn’t the Hilton Hotel.”)

Lynch described the average person’s reaction to hearing about more deaths in county jails: “They’re just like, ‘Oh, another one. Did you hear, another one?’” She paused. “This is not a game. This is not a book. This is reality. People are growing up without a father, a mother, and it’s not meant to be.”

Garcia appears to have granted more interviews than his predecessor, but the Erie County sheriff’s office has not otherwise warmed to transparency and oversight under new management. The Buffalo News had to sue Garcia’s office in 2022 in an effort to force the release of body camera videos that appeared to show a deputy kicking a restrained inmate in or near his head. Garcia claimed he was withholding the footage out of respect for the inmate’s privacy.

The officer in question, Daniel Piwowarczyk, acknowledged that he had kicked the man but claimed it was in the shoulder, not the head. (Piwowarczyk was suspended in 2019 for allegedly entering inaccurate and false information into a disciplinary report, misrepresenting his actions.) Garcia’s professional standards division, which is run by the former head of the county Sheriff’s Police Benevolent Association, cleared Piwowarczyk of wrongdoing after an internal investigation determined he had not violated any sheriff’s office policies, including one that prohibits the use of force “against persons who are handcuffed or restrained unless it is used to prevent injury, escape, or otherwise overcome active or passive resistance posed by the subject.”

According to a Buffalo News story on the report, the sheriff’s office allows deputies “to use force against a restrained person to prevent injury to others” (this is consistent with what we read in the report and quoted above). Asked about that policy, Garcia said, “If somebody’s restrained, there’s no kicking, there’s no punching. I don’t know where [the News] got that; that’s 100 percent false. Once the cuffs are on, it’s over; you only use enough force to subdue the person.”

Despite the fact that his professional standards division seems to have a different understanding of his office’s policies, Garcia expressed confidence in the report’s findings. “If it was criminal and I took it to the district attorney’s office and he viewed it, he would have said, ‘[The deputy] kicked [the inmate] in the face when he was restrained,’” Garcia said. “He wasn’t restrained yet. I’m not sure; maybe he was. But either way [Piwowarczyk] didn’t kick him in the face. If he would have kicked him in the face, [Erie County District Attorney] John Flynn would have charged him. So I take the video to the district attorney and he says it’s not a criminal matter. The [inmate] didn’t make a complaint; there’s nothing.”

A spokesperson for the DA’s office confirmed Garcia’s account in an email. Garcia had “proactively brought the matter to our attention,” she said, and after reviewing the footage, the DA “found that we could not prove that a crime was committed beyond a reasonable doubt in a court of law.” In response to a series of follow-up questions (Did the DA or anyone in his office agree with The Buffalo News’ assertion that the video showed a deputy kicking a handcuffed prisoner in or near his head? Did the DA’s office recommend or believe that the deputy should be disciplined in any way? Does the DA share the News’ view that the video should be released to the public?), she replied, “No further comment from our office.”

Asked why the News had to sue to gain access to the video, Garcia reiterated his concerns about inmate privacy and implied that it was insulting for the paper to request the video after he’d already given a News reporter a copy of the internal report exonerating Piwowarczyk. “I mean, what are you looking for, you’re looking to gaslight something that never happened?” he asked, referring to the News. “So I said, ‘No.’”

Garcia said he would have had no problem with the deputy being charged and potentially fired if what he did “rose to the level of criminal behavior.” He had fired three officers already, he said: one for providing a convicted drug dealer incarcerated in a county jail with a cell phone and drugs, one who had been accused of having sexual contact with detainees and was ultimately arrested for assaulting a woman while off duty, and one for selling cocaine off duty.

“But if the guy didn’t do it,” Garcia continued, referring to Piwowarczyk, “I’m not just going to go [fire him] because I feel compelled by the newspaper. I’m the sheriff. I answer to the people.”

A state Supreme Court justice ruled on February 17 that Erie County had “no reasonable basis” for denying access to the tape and ordered the county to pay the News’ attorneys’ fees.

Ten days before the ruling, Garcia told me, “If the judge rules on this case, you can have it,” presumably meaning he would release the tape if ordered to. “I wouldn’t even mind inviting Mr. Spina up and having him watch it and go, ‘Here you go. This is what you’ve been fighting for?’” he added, referring to a Buffalo News reporter he considers an antagonist. After the ruling came down, he told the News he would explore options for appealing.

What has changed since Garcia took office is the sheriff’s relationship with April Baskin, the Democratic chair of the county legislature and one-time critic-in-chief of the office. In 2019 Baskin, a highly capable up-and-comer in county politics, became at age 36 the youngest chair in the legislature’s history and the only first-term legislator to become chair.

Baskin’s relationship with Howard was, in her words, “adversarial.” The two sparred at a 2021 meeting of the legislature’s Public Safety Committee. “You are invited here to answer our questions—do you understand that, Mr. Sheriff?” said Baskin, to which Howard replied, “I’m here by invitation and if this isn’t a two-way discussion that’s open and honest then I’ll conclude it right now.”

When The New Republic met with Baskin in Buffalo in November, it was clear she wanted to move on. She referred to Howard as “the previous sheriff” and avoided saying his name. Referring to his 2017 appearance under the Oath Keepers sign, she said that since Howard had stepped down as sheriff, she hadn’t seen any similar behavior from local law enforcement, and added that she was grateful that the county now has a sheriff “who is very clear and honest about how those ideologies do not really benefit the greater good of humanity.”

She also praised Garcia’s response to the racist massacre that took place in Buffalo on May 14, saying he was “the first person” to characterize it as “evil,” and adding that at such a traumatic time, “it was very important for the sheriff of the county to be able to just say it flat out for what it was.” (Garcia also praised his response to the shooting. “I was the first one to call out what this was all about,” he said. “I’m elected by the people; I’m not placed here by the county executive or the governor. I told the people what the people already knew: that this was a racist-motivated killing and the objective was to kill as many Blacks as possible in as little time as possible and move on to another target area.”)

Baskin said she and Garcia have a “workable relationship” and are “getting things done.” As an individual and “a representative of a marginalized and Black community,” she added, “I will always see places for growth when it comes to our criminal justice system. But what I have now is something that is drastically different than with the former sheriff.” She praised Garcia for his willingness to work with the public to “make our local criminal justice system a place where people can get the support that they need to do the time that they need to do … but also get the support from the deputies to be able to be strengthened and restored so that when they return to our communities, they are different people who make different decisions.”

At that point one person had already died after a brief stint in a county jail under Garcia’s leadership (another death followed several weeks later). Five months into the new sheriff’s tenure and after just two days in the holding center, Sean Riordan was nauseated, vomiting, sweating, and experiencing tremors, seizures, and falls. After his final seizure and fall, he became unresponsive and was transferred to a local hospital. His family took him off life support on his 30th birthday. His mother noticed bruises on Riordan’s throat, arms, and legs, as well as a cut eyelid and swollen eye (The Buffalo News obtained a photo of Riordan’s cut and puffy eye and reported that his face and eyes looked normal in a booking photo taken days earlier.)

Asked about Riordan’s death, Baskin said, “That death was not a suicide and suicide was something that was very common under the previous sheriff. Unfortunately, just as people can be at home with their family and just pass away of health issues, that can happen in our local hospitals, that can happen in schools, and that can happen in our jails … the disproportionate number of suicides that happened under the previous sheriff was the driving force for outrage. It’s unfortunate, but people will sometimes die in our jails, and when they do we now have a relationship with the sheriff where we get personal calls and are informed of the details.”

It was a striking departure from her reaction to the 2016 death of India Cummings, a 27-year-old woman who died from cardiac arrest caused by a pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, a blood ailment, and dehydration after a brief stint in the holding center.

Cummings’s mother Tawana Wyatt told me in 2019 that she had suffered many losses in life, but the loss of her daughter was “by far the worst.” After the New York State Commission of Correction Medical Review Board declared in 2018 that Cummings’s care was “so grossly incompetent and inadequate as to shock the conscience,” Baskin called on the New York Attorney General’s office to conduct an investigation. “I don’t believe it’s right. I don’t believe it’s human,” she said at the time, referring to Cummings’s treatment.

A few months after our meeting, a county medical examiner wrote in an autopsy report that there had been a “failure to adequately treat” Riordan for withdrawal from addictive substances, adding, “While the medical care that the decedent received prior to his admission to hospital was inadequate, it does not rise to the level of criminal neglect.”

Garcia told me the examiner’s remarks were “like saying, ‘Your actions didn’t rise to the level of being a pedophile.’” Medical examiners, he added, “are right until they’re not,” just as “a cardiologist is right until he’s not.” The doctor who examined Riordan was just an associate, he added, and he believed that “she was under pressure to do more than what her job was.” He particularly objected to her “disparag[ing]” jail medical personnel based on “implicit bias” regarding care at the holding center “because other people have died there.”

When I asked about Riordan’s bruises, Garcia said they were “due to whatever medical procedures that he had, chest compressions and so forth … when you suffer from cirrhosis of the liver, you’re prone to bruising and to bleeding.” When I pointed out that Riordan had a wound above one eye, Garcia said, “Well, when he passed out, he may have hit his head.”

In an email, The New Republic asked Baskin if her view of Riordan’s death had changed in light of the medical examiner’s report. A staffer sent back a statement that read, in part, “Mr. Riordan’s death was incredibly heartbreaking …We’ve made life-changing strides in the past few years in Erie County’s jails, we now have an independent advisory board, a full-fledged medically assisted treatment program, body-worn cameras, and multiple community organizations offering top-notch programs in our jails … [Mr. Riordan] was not forthcoming in his screening about his alcohol intake … I’ve spoken with jail management officials about this, and I know they are committed to seeing what improvements could work in our intake screening process.”

Garcia, too, said he wished Riordan “would have been forthcoming about his substance abuse.” He also noted that Riordan’s family, “with all due respect to them,” had had a five-year order of protection against Riordan and had told the sheriff’s office that he never drank and didn’t use heroin, even though he was in a methadone program.

“I get that,” Garcia added, “If my son dies, I want answers. But sometimes the answer is that somebody abused their body so badly by consuming so much alcohol ... this individual drank so much that he died of chronic ethanolism.” In a January editorial titled, “An inmate’s death underscores the urgent need for better training,” The Buffalo News characterized Riordan’s “abuse of heroin, cocaine and liquor, among other substances” as “his personal choice—a bad one,” but added that “acute withdrawal is a medical condition and it needed the appropriate medical treatment.”

No one, least of all Garcia, would deny that county jails have become a dumping ground for people with mental health and addiction issues (many have both; people who are suffering and lack access to health care often end up self-medicating with drugs and alcohol). Regardless of what Riordan did or didn’t disclose about his substance abuse, it’s unclear why no one thought to treat him adequately for withdrawal, given his symptoms and how common it is for inmates to experience them. “We’re set up to fail,” Garcia told The New Republic. “We don’t have the means to give individuals that come through the doors adequate medical help and there’s no facilities on the outside that will take them … there’s people that are just in need of a place to be under observation and counseling and therapy and medication, whatever, but not in a jail.”

Asked if he thought that one of the biggest underlying issues was a failure to raise enough tax revenue to fund needed services, Garcia answered in the affirmative: “Yes. We need to fund these services for sure ... there has to be somewhere in between hospitals and correctional facilities for people to be. And this might be taking a step back, but before they even commit crimes and are living out on the street. How does that happen? Some people are indigent; there’s going to be cases like that, but there’s people that come from middle-class and upper-class families, and they are on the street, homeless and committing crimes and they’re mentally ill and the family doesn’t know what else to do anymore. And they end up in my custody. That’s a disgrace. This is 2023 America. I think we need to take care of people.”

Garcia seems to have a keener grasp than his predecessor of the festering social wounds that make American jails and prisons uniquely hellish. Howard talked far less about mental illness and drug addiction than he did about good and evil. As a country, Howard said, we would do well to ask ourselves what makes us do “good things” and what makes us do “bad things.” There were, he added, “forces out there pulling us in both directions,” and “we should focus more on ... what can we do as a country to encourage more of whatever it is that makes us comply with the law, or comply with what is good, and refrain from doing what is bad.”

Conflicts between federal and state or local officials and between state and municipal officials over hot-button issues have, in recent years, become more common. After then-President Trump signed an executive order threatening to slash aid to communities that didn’t cooperate with federal officials to deport immigrants, mayors and councils in cities such as Boston, New York, Denver, L.A., and Santa Fe vowed to protect their residents from anti-immigrant federal policies. New Mexico Attorney General Raúl Torrez recently announced he was suing cities and counties that passed ordinances restricting abortion. “This, ladies and gentlemen, is not Texas,” he said. “A woman’s right to choose is guaranteed by the New Mexico Constitution.”

Like art and beauty, constitutional rights are in the eye of the beholder. A sheriff could, in theory, refuse to arrest an undocumented family because he believes that the Constitution protects them from discrimination based on race and national origin and arbitrary treatment by the government. He could refuse to arrest a woman who took abortion pills banned in certain localities based on his belief in the constitutional right to privacy that was the basis of abortion rights in the U.S. for nearly 50 years.

But most sheriffs who identify with the constitutional sheriffs’ movement would be likelier to, say, refuse on Second Amendment grounds to arrest someone for stockpiling assault rifles, or let somebody out of jail if they believed that person was being unlawfully detained. (Oath Keeper founder Stewart Rhodes’s estranged wife, Tasha Adams, said that Rhodes once wrote an award-winning paper arguing that the George W. Bush administration’s use of enemy combatant status to hold people suspected of aiding terrorism indefinitely without charging them was unconstitutional.)

Howard saw policies implemented by New York State to stop the spread of Covid-19 as unconstitutional. “My outrage at that was tremendous,” he said of efforts to restrict the size of gatherings during the pandemic. “The government could not control what we do in our homes. Our whole history of our country is against that … for the government to say you cannot gather and shut down churches, this is a First Amendment issue. During the Christian Holy Day of Easter, they were actually saying you could not have gatherings in your church. That does not sound like a free country. It sounds very much like a communist country.”

When The New Republic asked him to explain what he meant by “communist,” he conceded that he didn’t quite know. “It’s a good thing you said it, because communism, socialism, it all gets to be confusing,” he said. “But if we talked about a monarchy or oligarchy or democracy, it’s misleading that we think that we’re a democratic nation because we believe in democracy. A constitutional republic is really what our country is. We think it’s a democracy, but by design it’s a constitutional republic that makes decisions by majority rule, but within the limits of the Constitution … what I’m saying is that our commitment to and our belief in freedom is what sets us apart from most other nations in the world.”

Garcia is markedly less interested in these kinds of culture war debates. Asked if he thought there was an issue in law enforcement of officers joining or having cozy relationships with far-right groups, he said, “I’ve heard the term ‘Oath Keepers’ and extremist right, but I have never heard of anybody being associated with or even mentioned anybody’s name in that. Any extremist group is not welcome to the table, and by that I don’t mean political, I mean just extremist, any violence and racism and hatred.”

Asked how he screens for far-right ties, he replied, “We don’t take anybody with a pulse; a thorough background [check] is done. I don’t care whose nephew or niece you are; if you’ve been trouble, [if you post inappropriate comments] on social media, you’re not cut out to be law enforcement, at least not here.”

Garcia sometimes contradicts himself. One moment, he said he felt sorry for Riordan’s family; in the next, he expressed anger that they weren’t forthcoming about Riordan’s addiction. He is appalled that people whose main “crime” is poverty, mental illness, or drug addiction end up in jail, but he opposes bail reform policies that would help ameliorate that problem. He is also frustrated that the county won’t adequately fund mental health and addiction services—but not at the expense of more money for the sheriff’s office. He hopes one day to have enough funding to build a brand-new jail. He seems to believe he is making good-faith efforts at reform and suggested that The Buffalo News, and particularly recently retired staff reporter Matt Spina, has it in for him.

He especially resents being compared to his predecessor. “[Spina’s] whole career has been based on hammering Tim Howard,” he said, “And guess what? I’m not Tim Howard.” Referring to The Buffalo News, he added, “Every time my name is mentioned in their stories, it’s mentioned with Tim Howard and how many deaths occurred under his watch. Why do I have to own that? Why does it always have to be, ‘the handpicked successor of Timothy Howard?’”

When I pointed out that the death rate in county jails has so far remained the same under his leadership, Garcia said, “Each case is an individual case. You might have X number of people that died in any given neighborhood at one time. Now, how is it that they died? Did they die because they were mistreated? Or do they die because they died?”

The New Republic spoke to local activist and one-time candidate for sheriff Myles Carter at his mosque in November. Carter drew national attention when Buffalo police officers suddenly swarmed and tackled him from behind as he was being interviewed by a television news crew at a 2020 protest against police violence. (The police then arrested Carter and charged him with obstruction of government administration and disorderly conduct. According to the county DA, those charges were dismissed because the information the police provided did not support them.)

Did Carter, a vocal critic of Howard, believe that Garcia was any better? “No, no, no,” he said. “He was a cop himself. You can’t take a police officer and ask them to change the system that has conditioned them to be who they are,” he continued. “It just doesn’t make sense … It’s the same system they worked in for the past 25 years that’s paid off their mortgage, put their kids through school, and everything else. Why would they want to change that?”

On a record shatteringly warm afternoon that same week, The New Republic went to the holding center to talk to Lynch and the three other protesters who had shown up for that Wednesday’s rally. Lynch shared Carter’s belief that new leadership in the sheriff’s office had not produced better conditions in the jails. “It’s just another face,” she said of Garcia. “The other face makes people think that it is change, but it’s not. [Garcia and Howard] were on the same political line. They rallied for each other. It’s nothing different. They comfortable with it, and we gotta get ’em shaking so they not.”

Cloee Cooper contributed reporting. Interviews conducted for this article by Raina Lipsitz and Cooper will also be included in a forthcoming podcast Cooper is producing on far-right sheriffs.

Editor’s note: Lipsitz’s aunt, Nan Haynes, and father, John Lipsitz, represented plaintiffs against Sheriff Timothy Howard in 2010 and 2006. Haynes was also a plaintiff in a 2017 lawsuit that sought to compel Howard to properly document and report prisoner suicide attempts. John Lipsitz was cooperating counsel on the New York Civil Liberties Union’s 2014 lawsuit against the Erie County sheriff’s department for Freedom of Information Law, or FOIL, violations. He is currently serving as counsel for three Erie County pastors seeking to vindicate their right to visit Erie County jails under New York State law.