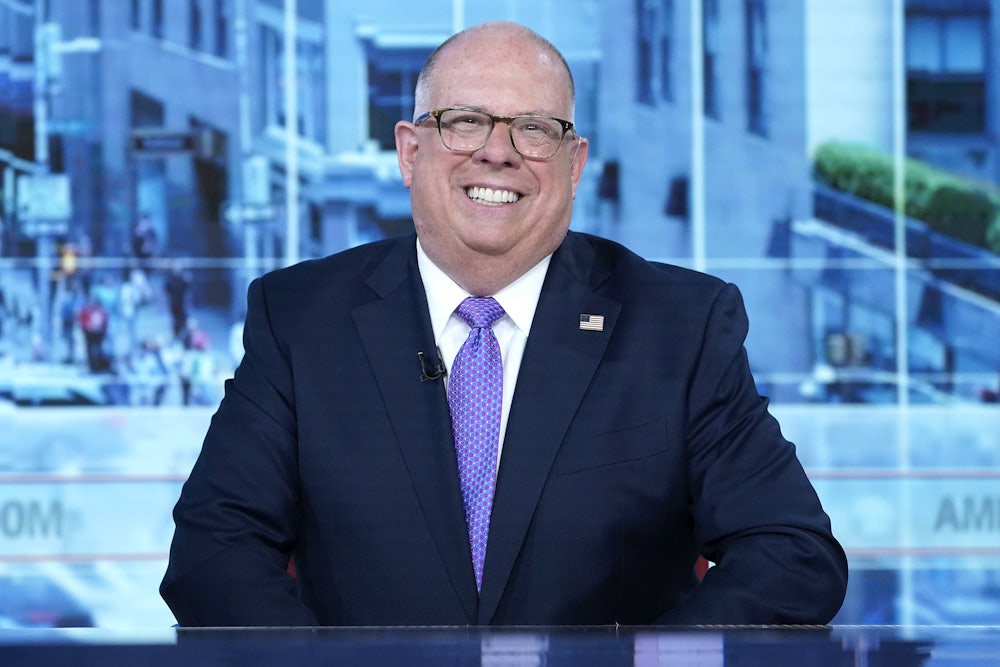

Larry Hogan ended his term as governor of Maryland earlier this year as one of the country’s most popular politicians. A moderate Republican, Hogan cultivated widespread acclaim in a blue state by emphasizing bipartisanship, de-emphasizing culture war issues, and generally refusing to rock the boat. (Indeed, many of Hogan’s accomplishments, like the state’s budget surplus, stemmed from inaction—in the case of the surplus, from understaffed public agencies.) During his two terms in Annapolis, Hogan was regularly touted as not just a foil for Donald Trump, but a potential savior of the GOP.

While Trump—and the growing roster of imitators attempting to snatch his crown in the party’s nascent presidential primary—built his political base around pugilism, vulgarity, and an authoritarian fixation on enemies both real and perceived, Hogan projected a down-to-earth and responsible mien. Those looking for sane figures in the Republican Party often turned his way, and it was easy to see why: Hogan left office with a staggering 77 percent approval rating.

Given Hogan’s popularity—and the press’s love of pumping up Trump alternatives—rumors about a possible presidential campaign have followed him for years. Even after Hogan’s handpicked successor lost to an über-MAGA candidate (Dan Cox, who tried to impeach Hogan for Covid restrictions, wanted to ban abortion, and promulgated the lie that the 2020 election was stolen), the rumors persisted. Hogan himself was said to be seriously thinking about a presidential bid and had spent the last several months doing the kinds of things that people who are running for president do, like visit restaurants in New Hampshire, or occasionally tell the press he was giving “very serious consideration” to a presidential campaign. It all made sense in theory: Hogan was popular and had run a state government responsibly and in a bipartisan manner. Once upon a time, this was a clear path to success for GOP wannabes. Even as that path came to be choked more and more by radicals, its viability remained: In 2016, it was called “the establishment lane.” Before Donald Trump, it’s where the Republican Party almost always got its presidential nominees.

On Sunday, however, Hogan announced he wouldn’t be running for president after all. Writing in the preferred organ of moderate Republicans—The New York Times opinion section—Hogan laid out his reasoning. The big reason why he had decided against running was that he had absolutely zero shot of winning. “I would never run for president to sell books or position myself for a cabinet role,” he wrote. “I have long said that I care more about ensuring a future for the Republican Party than securing my own future in the Republican Party. And that is why I will not be seeking the Republican nomination for president.” Instead, Hogan argued—convincingly—that he is best placed to bring about change from outside the party.

What’s most notable about Hogan’s decision is that it’s not even the least bit surprising. The establishment lane simply does not exist anymore. It got shut down in 2016, after getting clogged with wreckage. Jeb Bush, the presumptive favorite at the start of the contest, crashed and burned, spending $150 million to earn just four delegates. John Kasich and Marco Rubio fared little better, winning just four contests between the two of them. The only thing any of these candidates—and the raft of even more pathetic aspirants who joined them—accomplished was getting in one another’s way. But even if they had cleared the field, the result would have hardly been different: Republican voters don’t want an establishment candidate.

Even the Republicans running in 2024 who could opt to go in as establishment-ish candidates—Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, most notably—are positioning themselves as frothing outsiders and rabid culture warriors. In today’s Republican Party, a 77 percent approval rating is an albatross around your neck. The Hogan program, which successfully earned steady support through bipartisan leadership and a fixation on the hoary clichés of an older generation of Republicans (fiscal responsibility, etc.) is a recipe for disaster. Hogan never stood a chance.

What made Hogan popular in Maryland also makes him an untenable Republican presidential candidate. As New York’s Ed Kilgore notes, Hogan is “a pro-choice, anti-MAGA member of that very endangered species: the moderate Republican. Its habitat has been shrunk to a few extremely blue Northeastern states where the GOP is so weak that being an actual RINO is the only path to any kind of statewide office.”

Hogan’s moderation was, of course, as much a media invention as anything else: Fantastically corrupt, he raked in millions as governor while moving money earmarked for public transit in Baltimore to road construction projects. As my colleague Alex Pareene wrote in 2020, Hogan’s recipe for success was somewhat different from the media invention: “Remove affective conservatism—reactionary culture-war-stoking and blunt appeals to white supremacy—from the plutocratic agenda, and well-off liberals may find themselves far more receptive to a right-wing politician.”

Still, Hogan’s unwillingness to base his entire political identity around stoking the culture war is precisely what’s prematurely ending his political career. Which only makes his insistence that his side is winning the battle for the soul of the GOP even more bizarre. Per his Times op-ed:

I believe the tides are finally turning. Republican voters are growing tired of the drama and are open to new leadership. And while I’m optimistic about the future of the Republican Party, I am deeply concerned about this next election. We cannot afford to have Mr. Trump as our nominee and suffer defeat for the fourth consecutive election cycle. To once again be a successful governing party, we must move on from Mr. Trump. There are several competent Republican leaders who have the potential to step up and lead. But the stakes are too high for me to risk being part of another multicar pileup that could potentially help Mr. Trump recapture the nomination.

Hogan is staying out of the way because he knows that a crowded field only helps Trump. This is true, to be fair. But the idea that defeating Trump is the be-all and end-all of saving the Republican Party is an absurd idea. The candidates who are running against Donald Trump have adopted a variety of Trump-ish positions and aesthetics. The person most likely to succeed him, DeSantis, has literally modeled himself after Trump and has risen to prominence within the Republican Party attacking boogeymen: going after Disney, attacking transgender citizens, fighting “critical race theory,” and the like. DeSantis may be less disruptive than Trump in some limited ways, but the idea that he embodies a significant departure from the horrors and excesses of the Trump presidency is ridiculous. His best chance of winning the nomination is convincing voters that he’s prepared to go much further than Trump.

Indeed, the fact that DeSantis began his ascent as an establishment figure is illuminating. Establishment Republicans used to carefully pick their spots where they played to their rabid base; but the road to success involved a pivot to the mainstream, with gestures toward a desire to be a president for all Americans. Trump was the first to reject these strategies, and DeSantis is following suit. He’s not opting for a kinder or gentler form of conservatism. He’s certainly not adopting Hogan’s bipartisan approach. He’s a dyed-in-the-wool culture warrior who wants to use the power of the state to punish those that he and his party have deemed corrupting or corrosive influences. It’s a Trumpian form of authoritarianism. Hogan will happily endorse it.