In 2001, a pair of German filmmakers showed up at the door of Nikolai and Nadezhda Kaluzhni, an elderly couple living at 14 Tarnowski Street, apartment 3, in the Ukrainian town of Drohobych. When the Kaluzhnis learned that the visitors were making a documentary about Bruno Schulz, they understood the reason for the visit. During World War II, the building had been commandeered by an SS man named Felix Landau, who lived there with his mistress and two children from an earlier marriage. To decorate the children’s playroom in “Villa Landau,” he compelled Schulz, a writer and artist who was a local high school teacher, to paint murals of fairy-tale characters, including Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.

Sixty years later, Schulz was regarded as one of the most important Polish prose stylists of the twentieth century, on the strength of two slim volumes of stories, Cinnamon Shops (1934) and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass (1937). Starting in the 1960s, when his work began to be translated, he became a major influence on Jewish writers in other languages, notably the Israeli novelist David Grossman and the American Cynthia Ozick, each of whom incorporated the story of his life into a novel. And Schulz’s murals loomed large in that story.

In exchange for the paintings, Landau took Schulz under his protection, exempting him from the regular transports to the Belzec death camp that reduced the Jewish population of Drohobych from 15,000 before the war to about 800 at its end. Landau murdered many other Jews, however, and in November 1942 he shot a dentist named Adolf Löw, apparently in order to steal the gold fillings from his teeth. Löw had been under the protection of another SS officer, Karl Günther, who took revenge by shooting Schulz on the street a few days later. “You killed my Jew, I killed yours,” Günther reportedly told Landau. The casual, dehumanizing horror of the story—a great writer murdered to satisfy a petty rivalry between Nazi thugs—has made it notorious.

After the war, Villa Landau was segmented into apartments, and over the years it was visited by researchers hoping to find Schulz’s murals, without success. The filmmakers who came in 2001, Christian Geissler and his stepson Benjamin, had studied the building and believed Landau’s former playroom was now the Kaluzhnis’ pantry, a small room about eight feet long by six feet wide. In his new book, Bruno Schulz, Benjamin Balint describes the moment when they entered the dim pantry: “their eyes scouted faint but discernible shadows of figures behind shelves swelling with tarnished pots and half-forgotten pickling jars … beneath smudges of mildew and several layers of pale pink paint.” Without realizing it, the Kaluzhnis had been living with Schulz’s fairy-tale scenes for decades.

Bruno Schulz starts with this moment of discovery and traces its ramifications in two directions. First, Balint moves backward into the past, exploring Schulz’s life and work in Drohobych before World War II, and his experience during the Holocaust. Then Balint circles back to tell the story of the rediscovered murals and their immediate “hijacking,” to use the subtitle’s word, and of a heated international debate over the legacy of Eastern European Jewry, one with important implications for twenty-first–century culture and politics.

Bruno Schulz had the misfortune to live in what the historian Timothy Snyder calls the “bloodlands” of Eastern Europe, a region where tens of millions were killed by war, revolution, and the Holocaust in the twentieth century. When Schulz was born in 1892, Drohobych was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; at the end of World War I, it became part of Poland, and when World War II began, it fell under Soviet and then Nazi occupation.

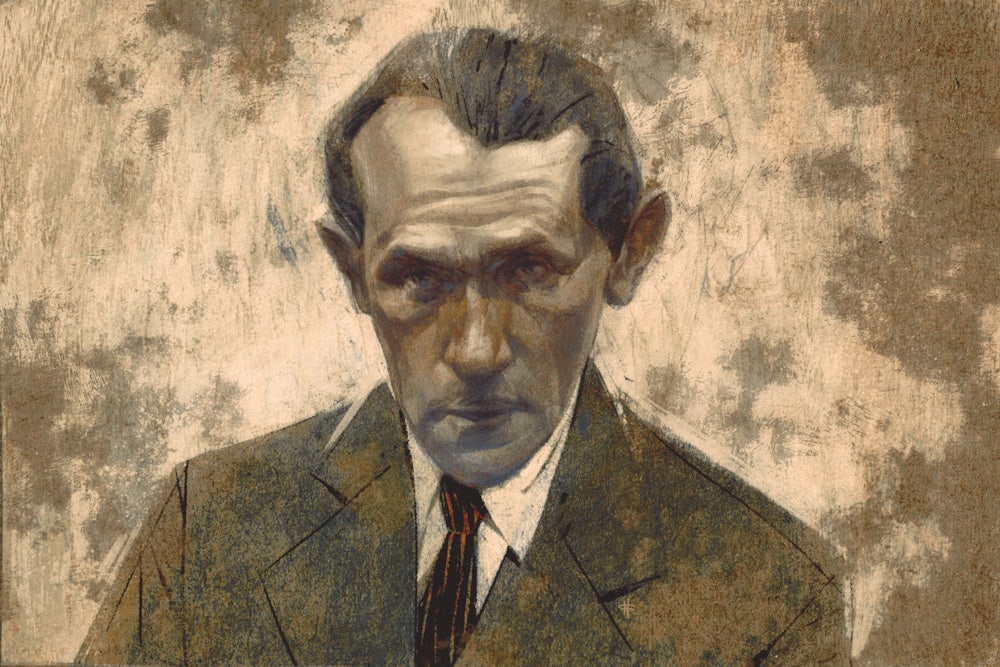

As history raged around him, Schulz led an almost unnaturally quiet existence. Other than a few years in Lviv as a student and in Vienna as a refugee, he never left Drohobych. He never married, had no children, and spent his days at a teaching job he loathed: “Every day I leave that scene brutalized and soiled inside, filled with distaste for myself and so violently drained of energy that several hours are not enough to restore it,” he wrote in a letter. He became a writer, it seems, almost by accident, when a friend told him that the fanciful accounts of Drohobych he included as postscripts to his letters should be turned into freestanding stories. The books that resulted were eagerly embraced by the avant-garde, who recognized a completely new note in Polish literature: Czesław Miłosz recalled that for young Polish poets in the 1930s, “Schulz’s name was surrounded by a special, magical aura.” Yet the books brought him neither fame nor wealth, and Balint writes that Schulz “neither dared think of himself as destined for acclaim nor expected to be read by generations yet unborn.”

After World War II, Drohobych was annexed by the Soviet Union, and after 1991 it became part of independent Ukraine. The new country had little interest in its Polish literary heritage, and when Schulz’s murals were discovered, representatives of Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust memorial, suggested the murals would be better off there. “Listen, who visits Drohobych? But two million people visit Yad Vashem annually,” one reportedly told Christian Geissler.

The debate that followed makes Bruno Schulz a perfect sequel to Balint’s previous book, the award-winning Kafka’s Last Trial, which dealt with a similar tug-of-war over a cache of manuscripts by another Jewish writer, Franz Kafka. In that case, the manuscripts were already in Israel, and the question was whether the woman who inherited them had the legal right to sell them to a literary archive in Germany. Israel’s Supreme Court decided the manuscripts were part of the country’s cultural heritage and awarded them to the National Library of Israel. Though the 2016 decision came in for criticism, many countries have similar laws forbidding the export of heritage artifacts—even if Kafka’s German manuscripts aren’t part of Israeli culture in any straightforward sense.

Schulz’s murals wound up in Jerusalem in a more dubious fashion. As Balint explains, their discovery created a major headache for everyone involved. Drohobych was a small town in a poor country, with no funds to preserve the murals, much less to turn the building into a Bruno Schulz museum, as some scholars proposed. And the Kaluzhnis quickly got tired of reporters showing up at their door. “Who could have imagined we’d never get any peace thanks to some old smears on the wall?” Nadezhda told one newspaper. Nikolai threatened to “take an ax” to the murals and solve the problem once and for all.

The most convenient solution was for the murals to disappear. Accordingly, in May 2001 the head of Yad Vashem’s restoration department and two associates came to Villa Landau and cut the most important images off the walls, leaving a few sections behind. The paintings were loaded into crates and driven across the border to Poland, where they were put on a plane to Israel. When the news broke, of course, there were loud recriminations. Balint notes that Polish newspapers, which had been relatively indifferent to the discovery of the murals, were outraged by what they called a theft.

In fact, the legal status of the murals was ambiguous. Ukrainian law prohibited the export of cultural treasures created before World War II, but Yad Vashem argued that Schulz’s murals had “never been registered as national assets,” and that the museum had acted with the permission of local authorities. (Balint writes that two sources told him that the mayor of Drohobych received $900,000 in bribes to allow the removal.) Israel has long argued that countries implicated in the Holocaust have no moral or legal claim on the cultural treasures of murdered Jews. The murals belonged in Yad Vashem, the museum said in a statement, because they offered “a powerful and unique testimony to the annals of the Jews under the Nazi regime.”

Balint is clearly skeptical of what he calls Israel’s “elastic assertions of ‘moral right.’” But he doesn’t come down explicitly on either side of the debate, allowing various Ukrainians, Poles, and Israelis to make their own arguments. Perhaps the most telling response he quotes comes from an unnamed woman who is one of the few remaining Jews in Drohobych: “The implication from Yad Vashem is that I should leave. If this place isn’t good enough for objects made by the hands of Jews, it’s certainly not good enough for living Jews.”

This suggests why the fate of Schulz’s murals provoked such a stormy debate, and why it is worth writing a book about. It’s not that the murals themselves are great works of art. Now that they can be viewed on Yad Vashem’s website, anyone can see that they are generic fairy-tale scenes: a princess in a blue ball gown, a gaily dressed soldier driving a team of horses. Rather, the murals matter because they raise symbolic questions about Jewish history and Zionism. Was Eastern Europe ever really home to the Jews, a place their descendants can embrace in memory, albeit sadly? Or was it just another of the many hostile zones where Jews suffered while waiting to be restored to their homeland, the land of Israel?

This question, with all its implications for the twenty-first century, lay behind the Schulz controversy. If the Jews were once an Eastern European people, then the murals should have stayed in Drohobych, where Schulz spent his entire life and became a great Polish writer. If not, then it was right to bring the murals to Israel, as testimony to the murder of a great Jewish writer. As Balint writes, “Was the 2001 ‘Operation Schulz’ a clandestine rescue—a homecoming to a home Schulz could not have envisioned—or a usurpation? An emancipation or a theft?”

There is, however, a terrible irony about this debate, which Balint doesn’t fully capture. Starting in the late nineteenth century, the question of whether the Jews belonged in Europe or Palestine, as it was then called, occupied the red-hot center of Jewish politics. Many professionals and intellectuals were drawn to the idea that assimilating to German or Polish or Russian culture would allow them to escape persecution. But after two or three generations of assimilation, antisemitism in Germany, Austria, Poland, and Russia was clearly getting stronger, not fading away. That left most Jews ready to embrace the more radical prescriptions of Zionism, which urged them to leave Europe for Palestine, and of communism, which promised that the destruction of the existing social order would mean an end to ethnic and religious hatred.

Schulz’s writing can be seen as a triumph of assimilation. Balint argues that Jewishness was never an important part of his identity: “Schulz neither acquired a religious education nor delved into Judaism to give sense and substance to his life.” He is particularly skeptical of critical attempts to find a Jewish dimension to Schulz’s writing. “His fiction seldom makes explicit reference to Jews,” Balint points out, and, “like Kafka, he strips his stories of most ethnic and historical markers.” Other Jewish writers of his time and place wrote in Yiddish, as Isaac Bashevis Singer did, or in Hebrew, as S.Y. Agnon did, both Nobel Prize winners. Schulz wrote in Polish, and was celebrated in the 1930s by writers of the Polish avant-garde. All this seems to support the idea that, as Benjamin Geissler stated in an open letter, the “work of Bruno Schulz belongs to the cultural heritage of eastern Central Europe.”

Yet this interpretation of Schulz’s work clearly misses something. After all, what turned him from an admired Polish stylist into a world-renowned writer was his reclamation by fellow Jewish writers. David Grossman’s masterpiece See Under: Love, published in 1986, is a variation on Schulz’s themes and includes Schulz as a character; in a fantastic sequence, he escapes death by transforming himself into a salmon and swimming away into the Baltic Sea. Cynthia Ozick followed suit in 1987 with The Messiah of Stockholm, a novella in which a Swedish writer becomes convinced that he is Schulz’s illegitimate son. Both novelists were obsessed with Schulz’s lost novel The Messiah, whose unfinished manuscript was supposedly smuggled out of Drohobych before he died. For some Jewish writers, waiting for The Messiah is a secular equivalent of waiting for the Messiah, as religious Jews have been doing for millennia.

These and other admirers, including Philip Roth and Jonathan Safran Foer, weren’t just responding to the biographical fact of Schulz’s Jewishness. While it’s true that the word “Jewish” never appears in his stories, Schulz clearly belongs to the same world as his contemporaries Franz Kafka and Walter Benjamin. Like them, Schulz wrote about frustrated messianic longing, his resentment and awe of his father, and the tormenting intuition that the world is a cryptogram that will never be solved.

Schulz’s two dozen or so tales almost all take the form of childhood reminiscences that morph into surrealism, as his lush prose blurs the boundary between the animate and the inanimate. These stories revolve around the narrator and two characters—Father, an alternately terrifying and pitiable figure, and Adela, the family maid, who is the focus of masochistic fantasy. In the story “A Visitation,” Schulz stages a tableau in which Father seems to be struggling to defecate and striving with God at the same time:

We heard the pounding of a struggle and my father’s groan, the groan of a titan whose hip is broken but who rages on. I had never seen the Old Testament prophets, but at the sight of this man, brought down by divine wrath, straddling an enormous porcelain chamber pot with his legs spread wide apart, screened by the whirlwind of his arms, by a cloud of despairing contortions above which his voice, alien and hard, rose even higher, I understood the divine wrath of holy men.

The reference to a broken hip connects this scene with the biblical story of Jacob, who wrestled with an angel and came away with a similar wound. The sexual masochism that pervades Schulz’s work often feels like a Freudian equivalent of this holy injury. The same affinity for weakness helps to explain Schulz’s embrace of literary decadence, a fin de siècle style that was already well out of date by the time he was writing. His aesthetic creed can be found in a typical sentence in “A Second Autumn”: “Beauty is an illness, my father taught, it is a type of shivering caused by a mysterious infection, a dark portent of decay arising from the depths of perfection and welcomed by perfection with a sigh of deepest happiness.”

Schulz was never a Zionist—unlike Kafka, who was preparing to immigrate to Palestine when he died of tuberculosis. But he seems to offer a Zionist parable in his story “The Night of the Great Season,” in which Father’s flock of birds, dispersed by Adela in an earlier story, returns to him:

Several of them were flying on their backs; they had heavy, clumsy beaks that resembled padlocks and latches, they were burdened with colorful growths, and they were blind. How moved Father was by this unexpected return, how amazed he was by the avian instinct, by this attachment to the Master that that exiled tribe had nursed, like a legend, in their soul, so that, at long last, after many generations, on the final day before the tribe’s extinction, it would be lured back to its primeval fatherland.

Certainly, Schulz’s life and death offer clear proof of the failure of Jewish assimilation as a survival strategy. Balint observes that, in the 1930s, the majority of Poles felt their country would be better off if the Jews disappeared; the Nazis simply took that idea to its ultimate conclusion. Almost a century later, the debates chronicled in Bruno Schulz, and even the book itself, feel somewhat neurotic—a perfect example of the melancholia that Freud described as mourning gone wrong. The debate over whether Jews belonged in Eastern Europe used to be political, because it was about the future of living people; today it is merely cultural, a tussle over the relics of the dead.