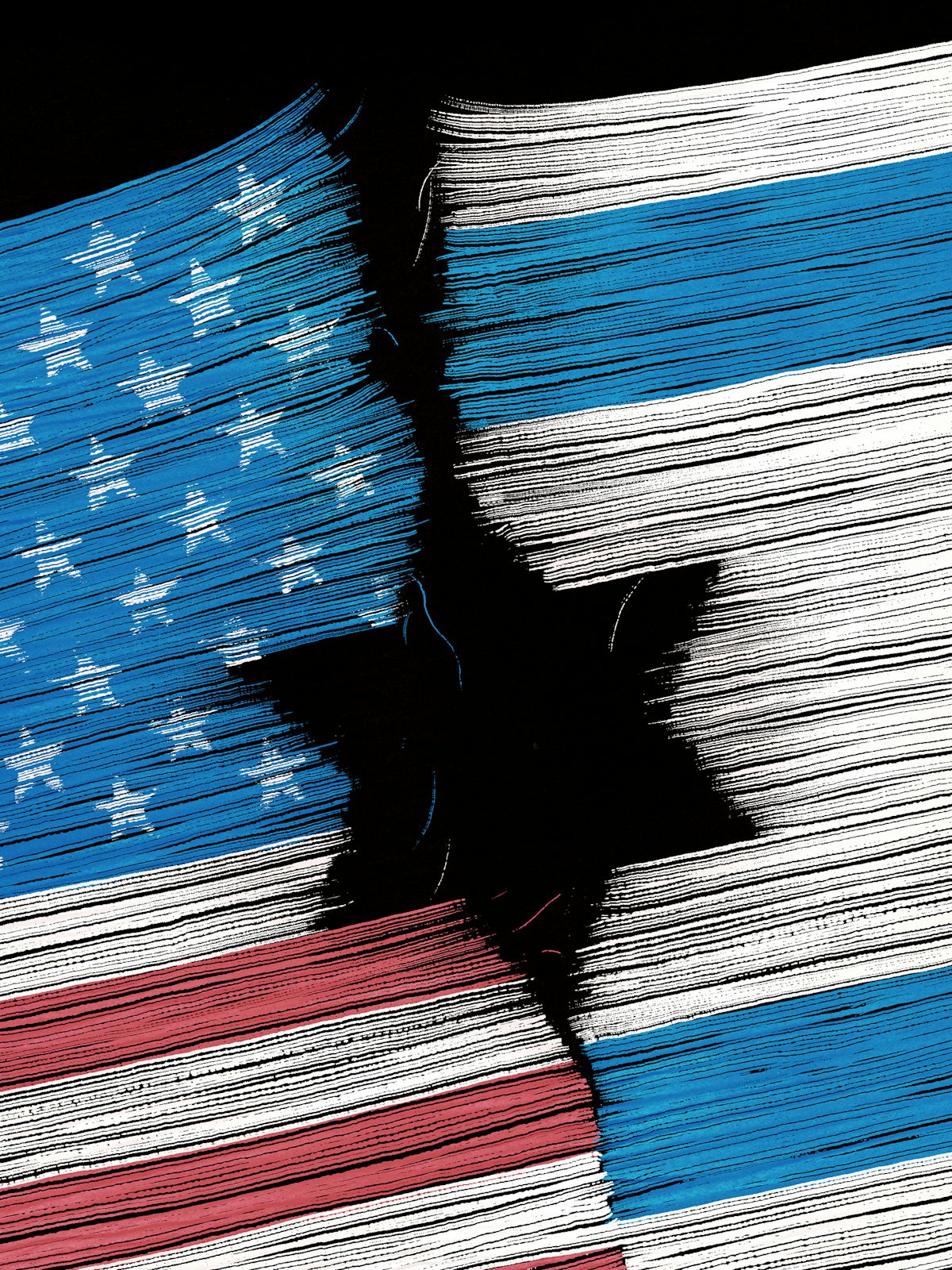

One sign read PEACE. Another, EQUALITY. Another, JUSTICE. Still another, in handwritten letters, ISRAEL YOU ARE LOSING U.S. JEWRY.

The protesters had gathered outside the Israeli Embassy in Washington, D.C., in early January, in the first days of the new, far-right governing coalition of Israel. They were there with Americans for Peace Now, or APN, a U.S.-based nonprofit dedicated to achieving a political solution between Israelis and Palestinians. There were about 100 people there, according to Hadar Susskind, the group’s president and chief executive officer. Much of the group was part of a 40-and-older cohort that, he told me, had grown up with the idea that their “job” as American Jews “is to support Israel.” There were people out there who may have never imagined that they would one day be protesting at the Israeli Embassy.

But this was a rally for Israel, he said: “For the Israel we believe in and the Israel we support.” What it was against, he said, was “felons and fascists and fundamentalists.” He had said this to the crowd that day, too, bundled up under a clear blue sky. Susskind said that he and APN got messages of support from Americans all across the country. There is a sense, he said, that someone has to choose to stand up and speak out.

And so this moment is a potential eye-opening turning point for liberal American Jews. The APN protest may have drawn tens instead of hundreds or thousands, but the expressions of support Susskind says he received were emblematic of what millions of American Jews must be thinking: Is this new government—which includes a member who brags that he is a homophobe and fascist, which wants only to expand the settlements and doesn’t even pay lip service to the idea of peace—too much for liberal American Jews to swallow? Is liberal American Jewish support for the state of Israel dying?

The new government is forcing, among some liberal American Jews, a reassessment of their support for Israel over the past several decades—ever since the occupation began in 1967 and Israel moved to the political right in the following decade, if not even earlier. Some American Jews are now confronting, more fully than ever before, the possibility that this extremist government is less outlier than culmination of a process that has been unfolding in Israel for a very long time. “The fundamental question all of us have to confront is: Is this government an aberration, or is this government a logical outcome of what’s been going on for the last 50 years?” said Shaul Magid, distinguished fellow in Jewish studies at Dartmouth College. He then put it another way. “How could this be happening?” he asked, immediately answering his own question: “It was always happening.”

Most American Jews are liberal. Not all are, of course, and it’s important to note that some do not see the new Israeli government as something to protest. Orthodox Jews, who make up roughly 10 percent of American Jews, tend to be politically more conservative. And some mainstream, legacy American Jewish organizations, which tend to carefully walk a nonpartisan or bipartisan line, expressed support for the new Israeli government, or at least offered congratulations on its formation.

In a statement, the American Jewish Committee, or AJC, congratulated Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on forming a new government, adding, “We trust that Israel will continue to uphold the values that have allowed it to stand out as a beacon of freedom in the Middle East and as a source of pride and spiritual sustenance for the Jewish people as a whole.” The American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC, offered similar congratulations and said, “Once again, the Jewish state has demonstrated that it is a robust democracy with the freedoms that Americans also cherish.” The Anti-Defamation League, or ADL, congratulated Netanyahu on forming a governing coalition, though it added, “We remain deeply concerned by the inclusion, appointments and authorities expected to be given to individuals and parties in this Israeli government whose policies on Israel’s judiciary, relations with Israel’s minority communities, LGBTQ rights, religious pluralism, and Palestinian affairs historically run counter to Israel’s founding principles.” (AIPAC did not respond to a request for comment for this article, and the AJC declined to comment. The ADL directed me to its statement.)

But roughly 70 percent of American Jews identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party, which is to say that it is a fact of American political life that the majority of American Jews lean liberal.

The current Israeli government, of course, is not liberal, and in fact has abandoned any pretense of liberalism or even of moderation. The governing coalition includes figures such as Itamar Ben-Gvir, an admirer of Jewish supremacist Rabbi Meir Kahane, who threatened Yitzhak Rabin on television weeks before his assassination. More recently, ahead of the latest parliamentary elections, Ben-Gvir urged police to open fire on Palestinians. He is now the minister for national security. Then there’s the finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, of the Religious Zionism Party, who proudly describes himself as a “homophobe.” He also supports full annexation of the West Bank without citizenship for Palestinians, allegedly planned to attack motorists to protest the 2005 disengagement from Gaza, and has advocated for separate Jewish and Arab maternity wards within Israel. The justice minister, Yariv Levin, is moving ahead with a plan that would severely weaken the country’s judiciary, granting the government total control over judicial appointments and hampering the ability of the Israeli Supreme Court to strike down laws. Netanyahu, the prime minister and the person who assembled this government for the purpose of returning to power after roughly a year and a half away, is on trial for corruption, and many critics believe that the judicial overhaul is being fashioned to help him escape punishment (Netanyahu has denied that this is the intention). The Israeli right, meanwhile, believes the court has liberal bias.

All this is to say nothing of the new government’s attitude toward Jews outside of Israel. There were reports that coalition members, before formally joining the government, were advocating to recognize only Orthodox conversions for considering eligibility for aliyah, or immigration to Israel; most American Jews are not Orthodox. Amichai Chikli, the minister for diaspora affairs, has said that he believes the pride flag is an anti-Zionist symbol; American Jews, by comparison, were some of the strongest supporters of same-sex marriage in the United States. Chikli has bashed not only views that Reform Jews hold, but Reform Jews themselves, last year telling The Jerusalem Post, “The Reform movement has identified itself with the radical left’s false accusations that the settlers are violent, so they have earned the criticism against them, and I cannot identify with them.” Reform Judaism is the largest Jewish denomination in the United States.

These and other developments have left liberal American Jews feeling at odds with, or even alienated from, the current government of Israel. “Everyone I’ve talked to within the non-Orthodox community closely following the events are quite concerned if not distressed,” said Rabbi Rick Jacobs, president of the Union for Reform Judaism, who described certain figures and proposed policies of the current government as “literally at odds with how we understand Judaism and democracy.”

Perhaps it is that sense of ideological difference with the current government that has shaken American Jews. Perhaps it is the coalition’s members’ contempt for many American Jews. Perhaps it is the obvious, heavy-handed approach the government is taking. Perhaps it is a combination of all three. In any event, Susskind said, something has changed. “I think what’s happening is that a lot of people—U.S. Jews in this particular case, though it extends beyond that—are waking up to an Israeli government that’s fundamentally different than anything we’ve seen before,” he said, adding, only half-jokingly, that the U.S. equivalent of this governing coalition would be if Donald Trump were back, but his Cabinet were made up of far-right Representatives Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert, and also “the dude with the horns” from the January 6, 2021, storming of the Capitol.

And so there was a protest at the Israeli Embassy. But not only that. More than 330 American rabbis signed a letter vowing not to allow far-right members of Israel’s governing coalition to speak at their congregations. Since they were Reform, Reconstructionist, and Conservative, it is perhaps unlikely that Jews who recognize only Orthodox Judaism would wish to attend in the first place. Still, it sent a message that, for them, this was not business as usual.

Rabbi Andrew Vogel, one of the letter’s signatories, and the senior rabbi at Temple Sinai, a Reform congregation in the heavily Jewish town of Brookline, Massachusetts, told me the letter was “pretty easy to sign.” He continued: “Like many American Jews, I’ve been watching with horror as the right in Israel grows…. We’ve been watching for a long time.” Vogel is not new to speaking up against the right wing and human rights abuses in Israel, and the new government didn’t come as a surprise to him, he said, but it is “antithetical to what Judaism stands for.” I asked Vogel what he made of criticism that he would sign a letter barring certain coalition members, but not Netanyahu, the person who put them in the government. “He’s probably not going to come speak at my synagogue,” he quipped, adding that if Netanyahu were to come to his area, he would protest, not “blacklist.” “I think we all acknowledge there’s a spectrum in the Israeli political system,” he added.

Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky of Ansche Chesed, a Conservative synagogue in New York City’s Upper West Side, changed the prayer for Israel that he says during services, replacing the standard prayer for the state of Israel with Psalm 122: “Pray for the Peace of Jerusalem.” In a blog post explaining the change, Kalmanofsky wrote, “We will pray that there be peace and serenity within Israel for all who live under her authority…. I do not pray that this government succeeds. I pray that Israeli society succeeds. And I pray that this illegitimate government fails, and that its Jewish supremacists crawl back under their rock.”

In an interview, Kalmanofsky was emphatic and pointed in his critique. The inclusion of extremist elements in the constellation that is the current coalition represents “a terrible, terrible turn toward Jewish supremacy, in the way we use the term white supremacy,” he told me, and it deserves to be “opposed with vigor.” “It’s not like we, guilty white liberals, woke up and realized there was an occupation,” he said. But “it hasn’t been that long ago that there were some hopeful signs.” A decade ago, Kalmanofsky attempted to block a discussion on Israel at Ansche Chesed because it would have included a supporter of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement, which he did not wish to have a presence at his synagogue. And Kalmanofsky has vigorously opposed using the word “apartheid” to describe Israel. But today, on the question of whether Israel is an apartheid state, he said that Ben-Gvir and Smotrich “basically want the answer to that question to be ‘yes.’”

I asked Kalmanofsky how his congregation responded to the changing of the prayer. “Of course,” he said, some people were “tremendously upset” and felt it was equivalent to renunciation of support for Israel. Some said he misunderstood the replaced prayer and should be praying for the enlightenment of the far-right ministers. “And I don’t agree with that,” he said. “I know who these folks are. I know what they stand for.” He continued: “I know my community. This was going to speak to my community, and it has.” The psalm, he said, has been received as “a well-placed liturgical gesture that helped a mostly, but not entirely, Zionist congregation not behave as though this is business as usual.”

Jewish elected officials, meanwhile—including those known to be ardent supporters of Israel—have made headlines for treating this government and its actions as something different.

Senator Jacky Rosen, a Democrat from Nevada, former synagogue president, and staunch supporter of Israel, reportedly asked not to meet with far-right members of the government on a recent trip to Israel. Rosen co-founded and is co-chair of both the Senate Abraham Accords Caucus and the Senate Bipartisan Task Force for Combating Antisemitism, so a request from a figure with those credentials is striking. Representative Brad Sherman, a California Democrat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee and longtime Israel booster, warned Netanyahu’s government in an interview in Haaretz that “mistakes” could cost it U.S. support. Representative Jerrold Nadler, a Democrat from New York City (and alumnus of Crown Heights Yeshiva), wrote a piece in that same publication under the headline, “AS THE MOST SENIOR JEWISH MEMBER OF CONGRESS, I NOW FEAR DEEPLY FOR THE U.S.-ISRAEL RELATIONSHIP.” “I am the most senior Jewish Member of Congress, and I represent the district with one of the largest percentages of Jews in the nation,” he wrote. “... That is why I am particularly distressed about the latest reported plans of Israel’s new minister of justice to undermine the judiciary and the system of checks and balances.”

I asked Halie Soifer, chief executive officer of the Jewish Democratic Council of America, which released its own statement critical of the new government, if she thought we would continue to hear expressions of concern from Democratic lawmakers. “I think we will,” she said. None of these statements, she stressed, are ultimatums, or are pulling support for Israel. But there are “truly extremist” members of this government, she said, and members of Congress, among other Jewish Democrats, will speak out over time. “It’s an obligation,” she said.

Almost 170 American Jewish communal leaders signed on to a statement calling for “critical and necessary debate” on policies taken by the new government, pointing in particular to the proposal to overhaul the judiciary and calls to bar non-Orthodox prayer at the Western Wall. The statement also said that actions like expanding Israel’s West Bank sovereignty could inflame regional tensions and cause further harm.

Outside of liberal U.S. Jewish circles and communities, there have been other signs to which people have pointed to suggest that something is different, that a reckoning is happening. There are thousands of people in Israel protesting the proposed changes to Israel’s judiciary. There was American attorney Alan Dershowitz (perhaps considered a liberal long ago but now better known for being, among other things, former President Donald Trump’s lawyer) explaining to Haaretz’s weekly podcast why Netanyahu, his longtime friend, is “wrong” to tamper with the judiciary.

There was an essay from Hillel Halkin, the American-born Israeli literary star, in the Jewish Review of Books. “This time it’s different,” he opened. “For years now, Israel has seemed to me like a man sleepwalking toward a cliff. Now we’ve fallen from it.” Yossi Klein Halevi, the American-born Israeli journalist, described in The Atlantic how he moved to Israel in the summer of 1982, “one of the lowest points in Israeli history,” as Israel fought a war with Lebanon. “These days, as Israel faces another historic internal crisis, I find myself thinking a great deal about the summer of ’82. Then we lost our unity in the face of an external threat. Now we’ve lost our unifying identity as a Jewish and democratic state,” he mused.

There are protests and letters and essays and podcasts all, essentially, saying that Israel has entered different, dangerous territory, threatening its relationship with Jews around the world—certainly with liberal American Jews—and its own status as a democracy.

There is, and has been for decades, one story about American Jews and Israel, and that story goes like this: Early in the twentieth century, many American Jews were wary of Zionism, not wanting to render themselves especially distinctive from other Americans or be accused of loyalty to any other country. The AJC was opposed to Zionism at first. But eventually this changed. Louis Brandeis, who in 1916 became the first Jewish Supreme Court justice, led the U.S. Zionist movement from 1914 to 1921. “Let no American imagine that Zionism is inconsistent with patriotism,” argued Brandeis, who stressed that Zionism was a democratic and just movement, compatible with the ideals America held most dear. “To be good Americans, we must be better Jews, and to be better Jews, we must become Zionists,” said Brandeis, in a sentiment echoed by Judge Julian Mack, a U.S. circuit judge and Jewish activist who, in the early twentieth century, was one of the founders of the American Jewish Committee and the first honorary president of the World Jewish Congress.

After the Holocaust and World War II, American Jews supported the advent of Israel. It was not only an important—many argue the most important—Jewish political project. It was, in more practical terms, finally a state that Jews could call their own, where, whatever else happened, they would not be persecuted as Jews. In the subsequent decades, and particularly following the Six Day War in 1967 and the Yom Kippur War in 1973, Israel moved to the center of American Jews’ politics and self-imagination. To be an American Jew, including a liberal American Jew, was to support Israel. Yes, there was an occupation, but American Jews could tell themselves that one day there wouldn’t be an occupation anymore, and that they supported a two-state solution. Yes, in the 1970s, Menachem Begin and his right-wing Likud Party came to power. Yes, in the 1990s, Likud’s Netanyahu led a mock funeral at an anti-Rabin rally months before his assassination, and yes, he became prime minister the following year. Yes, when J Street, an organization that called itself both “pro-Israel” and “pro-peace,” was founded, it was met with furious pushback and denounced as anti-Israel. And yes, Netanyahu embraced Trump tightly during his four years in office, even as most American Jews recoiled. But it was still the world’s only Jewish state.

In addition, there were moments of genuine hope. There was Rabin declaring, “You don’t make peace with friends,” and deciding to try for peace with his enemy, shaking hands with Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat on the White House South Lawn and signing the Oslo Accords of 1993. There was, at the end of President Bill Clinton’s time in office, the Camp David summit of 2000, where an accord was nearly struck. Yes, peace remained unachieved, and no, there were not two states, and yes, Oslo—and seemingly any peace process at all—appeared to slip into history. But liberal American Jews could tell themselves that these moments had happened, and they could, maybe, one day, become present politics again.

This moment, though, seems different. The new governing coalition is open in its extremism and illiberalism. For liberal American Jews, if this, our current moment, is an inflection point, it’s because “it undermines what I think was always a myth: Somehow American liberalism and Israel are symmetrical in some way,” Shaul Magid said. The liberal elements of Zionism were always marginal, he told me. Israeli forces expelled Arabs at the country’s advent. They placed Arab citizens under martial law for nearly 20 years after the country’s inception, and then, a year after that was lifted, began an occupation that continues to this day.

Settlements expanded. Jewish Israeli settlers in the West Bank have the same rights and freedoms as other Israelis; Palestinians in the West Bank do not. As of May 2022, just 5 percent of Palestinians in East Jerusalem had received citizenship since 1967. Kalmanofsky and many others have passionately made the case that Israel is not an apartheid state; Human Rights Watch, however, wrote in 2021 that, in some cases, deprivations of Palestinians were “so severe that they amount to the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution.” Magid, who coined the term “Zionization of American Jewry” to describe how central Israel and Zionism became to American Jews, said that today “Israel is just an illiberal country. That’s what it is.”

Some have argued that the difference between this Israeli governing coalition and its predecessors isn’t that it’s illiberal, but rather that it is simply more open about being illiberal.

Zaha Hassan, a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told me that she sees this government more as a continuation of what has come before than a change from it. But what is new, said Hassan, who was coordinator and senior legal adviser to the Palestinian negotiating team during Palestine’s bid for U.N. membership, is how open this government is about its intentions. Now, she said, the “folks at the steering wheel are much more aggressive, very open about what they want to do.”

Where earlier governments might at least give lip service to the idea of a two-state solution or desire for peace, this government, she said, is “not talking about even a Palestinian entity. They don’t care if there’s a Palestinian Authority of any kind.” Even the Palestinian flag was banned from public spaces: “The flag is a problem. That’s what’s concerning.”

But some liberal American Jews appear less concerned about the Palestinian flag, or the treatment of Palestinians generally, than they are about liberalism and democracy for Israeli Jews, or about Israel’s attitude toward Jews outside of Israel. Those who have been paying attention to the occupation and the rights of Palestinians are wondering what took liberal American Jews so long. Some stressed an inability—or perhaps an unwillingness—to connect the dots, and to understand and articulate the link between the treatment of Palestinians and the state of Israeli democracy, pluralism, and liberalism.

Much of the protest and pushback against this government has focused on attacks on the independence of the judiciary, or on the new government’s attitude toward non-Orthodox or queer Jews. But the history Hassan described, she said, is not distinct from but is in fact directly tied to what is happening now in Israel, and to Israeli democracy. “There’s a lack of awareness about how corrupting an occupation is,” Hassan said.

Khaled Elgindy, the director of the Middle East Institute’s Program on Palestine and Palestinian-Israeli Affairs, who previously served as an adviser to the Palestinian leadership in Ramallah, explained that, in an occupation, the population has no say in how they’re ruled. “When you have a system built on repression and you need ever more amounts of repression in order to sustain it, because people don’t like to have no rights, and that system is unaccountable and rule of law is very elastic and sometimes nonexistent,” he said. “It’s almost impossible to imagine how you can quarantine that.”

Lara Friedman, president for the Foundation for Middle East Peace, agreed that the extremism of the current government has its seeds in the occupation and, more generally, Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. “You cannot build a nation on the idea that not all human beings have rights…. You can’t do that for decades and not inculcate a political culture that is what you see today,” she said. For years, she added, people working on Palestinian rights have tried to make the case that the occupation doesn’t stop at the Green Line (the demarcation of territory captured in the Six Day War).

Friedman noted that many American Jews—including ostensibly liberal American Jews—have been more comfortable advocating for the rights of Jews in Israel than for Palestinian rights. “American Jews,” she said, got “riled up over women’s access to the Western Wall plaza. They’ll go to the mat for that.” But where illiberalism affected Palestinians, there was less interest. And now that the equities of Jews are hanging in the balance, “there’s a certain amount of, ‘well, if you’d been paying attention for the last 50 years.’”

Liberal American Jews, said Hasia Diner, a professor of American Jewish history at New York University, have long been like the little boy with his finger in the dike. “‘Yeah, things are bad, but it’ll take a tweak here and a new election there and we liberal Jews can go back to love of and adulation for the Israel that used to be,’” she said. And many now “continue to engage in a fantasy” that, until this election, or until Netanyahu, Israel was defensible as a liberal project. “They kind of leave out the fact that from 1949 to 1966, Arab citizens lived under martial law,” she said.

In 2016, Diner, a giant of Jewish studies and author of numerous acclaimed books on Jewish history, renounced Zionism in an op-ed in Haaretz. “It’s really hard to say, ‘Well, what we were taught and what we have propagated and what we’ve written and orated on and argued about is kind of built on a house of sand,’” she said. But the reality is that you “can’t have an oppression of one part of the population and have democracy. It’s going to come back and bite you in the neck.”

James Zogby has written a weekly column since 1992. “If there’s peace,” he remembers writing in one early edition, “someone forgot to tell the checkpoints, and someone forgot to tell the Palestinians.” Zogby, who is the founder and president of the Arab American Institute, said that “American Jews of a liberal bent” are “shocked about courts and the legal system and LGBTQ rights.” In 2016, Zogby, as one of Bernie Sanders’s representatives in crafting the Democratic National Committee’s party platform, pushed to include the words “occupation” and “settlements.” “They refused to put it in,” he told me. One woman from Hillary Clinton’s camp asked Zogby why he was picking on Israel, the only place where she, as a queer woman, felt safe. He remembers replying, “I appreciate that, but I can’t get in the freaking airport.” The word “occupation” was also left out of the 2020 platform.

The protests today, he said, are “all about the erosion of democracy in Israel proper.” But if you “don’t address the corrosive impact of occupation … you don’t address what is plaguing the country, and the Palestinians who form one half of the population.” He acknowledged that, for Jews who “have a feeling of attachment to that land, this is especially painful.” But “they have to take the next step,” he said. He understood that for queer Jews or Reform Jews or intermarried Jews, this is hard. But “what they also have to understand is: What they’re experiencing today is what Palestinians have experienced all along…. Your head has to come out of the sand at some point and accept responsibility to act on what you know is wrong.”

‘‘If we can stand up and say” that this government doesn’t deserve support, Susskind said, “hopefully it just shows other people that you can do that, and you don’t have to be cowed into silence.” And by that he meant elected officials, too. The political education of many members of Congress was such that “you don’t criticize the Israeli government,” he added. But it’s incumbent on American Jews, he said, to encourage their elected leaders to speak up for human rights, even if that comes with some political cost.

This past winter, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken addressed J Street’s national conference. Blinken, himself a Jew, stood before the flags of the United States and Israel and touted the nations’ shared values. And two months later, he flew to Israel, and again stood in front of the flags of the United States and Israel, this time next to Netanyahu, who was once again behind the lectern that read PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE, and who thanked Blinken for America’s help and continued friendship. And again, Blinken touted shared values, though this time stressing civil society, a clear reference to the Israelis in the streets protesting the proposed overhaul of the judiciary.

What does it look like for American Jewish civil society to act in response to the new government? For some, it means having no more to do with Israel. “There are members of my congregation who want to wash their hands of Israel,” said Vogel, the Brookline rabbi, adding, “I think that’s a huge mistake. I don’t think that’s responsible.”

Those who want to remain engaged—who care about Israel, and about what happens to it, and don’t want to give up yet—propose several different courses of action. “First, most important,” said Jo-Ann Mort, a writer and consultant who once described Israel to me as the closest thing she had to a religion, was to give “support and money to those fighting in the streets.” There are well-funded right-wing groups supporting the Israel they want to see, she said, pointing to the Kohelet Policy Forum and the Tikvah Fund. But the pro-democracy NGOs she works with are “all strapped.” She asserted that American Jews need to “put your money where your mouth is or where your heart is, now.”

Rabbi Jacobs, who called Israel “the greatest project of contemporary Judaism,” said, “We actually stand up for the things we care deeply about, and we advocate even more strongly for them. To me, that’s the stance of a responsible Judaism.” For Vogel, that work recently included bringing his congregation on a dual perspective trip. When I spoke to him, he had just returned from a 10-day tour with his congregation, co-led by a Jewish and a Palestinian guide. They met with activists. He attended a protest that Saturday night. At the end of the trip, he said, his congregants in attendance told him that they were angry about what they had seen, but that their “commitment to Israel has deepened.” He told me: “It would be easy to walk away, but that’s not the Jewish response. The Jewish response is to do the work.”

Synagogues are potential sites of discussion and discovery. They also, according to Kalmanofsky, should “think very seriously” about not inviting members of the new government. “I worse-than-cringe at the thought that some synagogue somewhere is going to have, ‘come meet the Israeli finance minister’”—that is, self-described “fascist homophobe” Bezalel Smotrich.

Some liberal American Jewish groups, meanwhile, are focused on their own government, and on encouraging their elected leaders to speak out, though getting elected officials to speak critically of Israel is no easy task. Israel has long had unquestioned bipartisan support in the United States, and for an elected official, Jewish or not, to challenge that is to both break away from congressional custom (and perhaps deeply held belief) and risk being attacked as an antisemite. “More and more Jewish Americans are alarmed,” said Logan Bayroff, vice president of communications at J Street. Bayroff said an increasing number of American Jews “are going to be speaking out more to say that the U.S. government and American Jewish leaders should do something about this.” Jewish politicians, in particular, who speak out about Israel could find their own faith and ethnicity weaponized against them: When then Michigan Representative Andy Levin, sponsor of the Two-State Solution Act, ran for reelection last year, voices from AIPAC along with former ADL leader Abe Foxman attacked him, with Foxman alleging that Levin used his Jewishness as a “cover.” Levin lost his primary race.

For J Street’s part, “We’ve always contested the idea that being ‘pro-Israel’ means supporting occupation, supporting the policies of the current government,” Bayroff said. And he wants elected officials to internalize that, too, and to say so publicly. “You have to have clear red lines,” he said, which “can’t just be expressed behind closed doors.” So far, however, those red lines have yet to be drawn, and it is far from clear that the Israeli government would respect them if they were. One early test will be the transfer of civilian authorities in the West Bank to Smotrich. The Biden administration has reportedly said that it would consider this a step toward annexation. Netanyahu took the step anyway. Now what?

Some, rather than coming out and saying what they will need to do in the face of this new government one way or another for Israeli democracy, are advocating for a “wait and see” approach. “It’s still early. Let’s not judge them by what they say, let’s judge them by what they do. So let’s see what happens,” Jared Moskowitz, a Florida Democrat who in January was appointed to the House Foreign Affairs Committee, recently told Jewish Insider. Other funders and organizational leaders have said the same.

But to others, that line now rings hollow. “They’re doing it,” Susskind said, referring to the Israeli governing coalition. “They didn’t wait.” Others note that a wait and see attitude and approach was part of the problem in the first place. “For too many years, the Jewish community has said ‘wait and see,’” said Mort. “We’ve waited and we’ve seen. And here we are today.”

There is another element to this, too, and that is time, and its passage, and how the memory of what once was fades, and the recognition of what is comes more clearly into view. With time, some Israeli politicians and officials have already come to say that they don’t need or care about the opinions of American Jews. In 2021, Ron Dermer, former Israeli ambassador to the United States, said Israel should prioritize evangelicals over American Jews. And, with time, American Jews may decide they do not owe loyalty—or anything else—to Israel.

Younger American Jews don’t feel they need to wait. For people of a certain age, who grew up with loyalty to Israel as a given, this is a moment of profound crisis. But for many young American Jews, it has never really been in doubt that Israel should be questioned. Younger American Jews, and certainly progressive younger American Jews, are not grasping the importance of Israel to themselves and their lives, because they don’t believe the story in the first place. They heard it in their synagogues and Hebrew schools, but they see something else online. For their parents, this may be a reckoning. For many younger American Jews, it’s more of a reaffirmation.

I asked Magid if he thought that American Jews writ large could imagine an American Jewishness that didn’t center around Israel. “We’re in a real tailspin,” Magid told me. “We don’t really know what to do, and we’re just kind of grasping at things to keep ourselves afloat.”

Perhaps we should expect the tailspin to continue—for Israel to keep heading down its current path, and for liberal American Jews to take one of three roads.

In one case, American Jews will respond by becoming more critical of Israel, and maybe even apathetic about it or distant from it. Not all, of course, but many, or even most. And American Jewish politics and communal life, which have been in no small part organized around Israel for the past several decades, will have to be about something else. The Zionization of American Jewry will reverse itself. Hasia Diner said she wasn’t sure what would come in its place. The tragedies of the twentieth century? They are slipping further into history. Nostalgia? “It can’t be grandma’s chicken soup,” she said. “By now, grandma’s an American-born lawyer who herself was maybe raised on grandma’s chicken soup.” For the past century, American Jews have worried about losing distinctiveness, and assimilation, and lack of Jewish continuity, and for the last half-century or more, support for Israel has been one answer to that. Perhaps American Jews will decide they need to come up with another answer.

In the second scenario, the shock will fade, and the outrage will, too, and there will be what there has been: American Jewish organizations stating their commitment to Israel and their shared Jewish and democratic values, and American Jews by and large believing them or not—but not challenging them. Perhaps not even Ben-Gvir is too extreme. Perhaps there will still be the story of American Jews and Israel and shared liberal values, even if it doesn’t have much to do with the reality of Israelis, or Palestinians. Even if, in continuing to tell it, American Jews reveal ourselves to be not so committed to liberalism after all.

But there is a third scenario, too. In this arguably less likely but more hopeful scenario, things are now finally, obviously, dramatically bad enough to snap people into action. American Jews and Israelis will commit to liberal values, and human rights and peace will prevail. In this case, universal human dignity, including the concerns of Palestinians, will not be treated as a side or separate matter, but understood as core to the issues of democracy and liberalism. And to liberal American Jewish values, too.