Confederate statues are coming down everywhere. Mississippi changed its flag. In the U.S. Capitol itself, statues of slavers and other white supremacists are being replaced. Virginia removed Robert E. Lee in 2020 and replaced him with Black civil rights activist Barbara Johns.

And yet, by far the most conspicuous remaining symbol of white supremacy on Capitol Hill still exists. People hardly ever talk about it. And it isn’t just a statue—it’s a whole building.

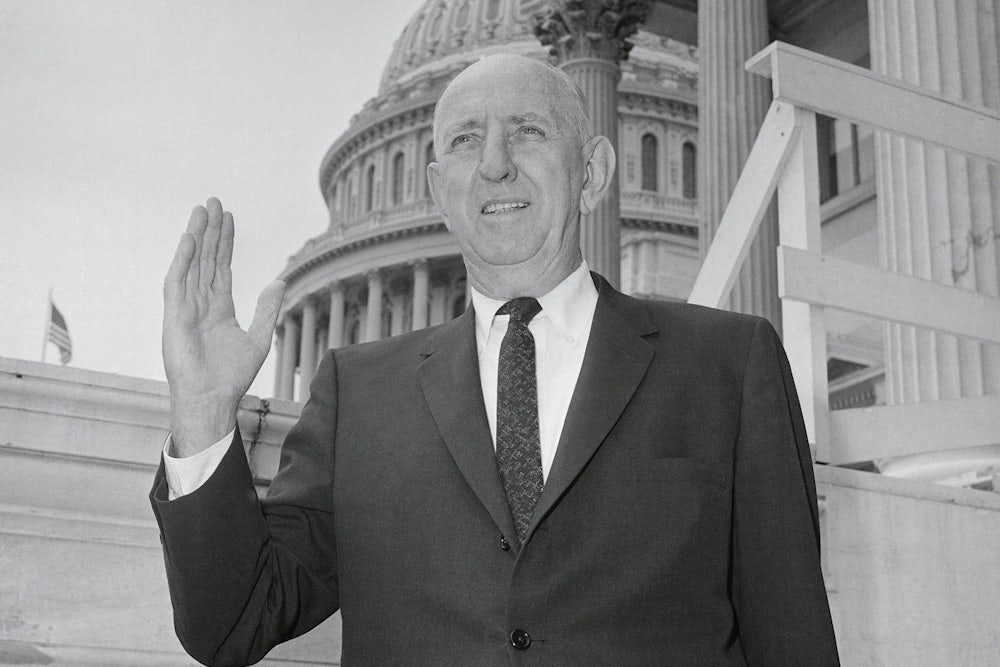

Senator Richard Brevard Russell Jr. was a remorseless bigot during his 38 years on Capitol Hill. The Georgia Democrat was an outspoken opponent of anti-lynching bills, school desegregation, and the confirmation of Thurgood Marshall to the Supreme Court.*

A year after Russell’s death in 1971, his colleagues renamed the Old Senate Office Building after the racist lawmaker. It’s a decision that could be revisited by the Senate anytime it wants to. “I’m a strong supporter of renaming the Russell Senate Office Building,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer told The New Republic last week. “In fact, I proposed to rename it after Senator John McCain shortly after his passing in 2018. There was some bipartisan support back then but not enough, and any effort to make this a reality now would need Republican cooperation.”

But Schumer’s view is not widely shared. “No,” said Senator Deb Fischer, a Nebraska Republican, when asked if she supported naming the Russell building for McCain. (She did not elaborate.) Other Senate Republicans, like Chuck Grassley and Ted Cruz, bristled more candidly at the notion of changing the Capitol complex in ways that are less racist. “They ought to find another building to name someone else after,” said Grassley, who served for over three decades with McCain in the Senate GOP conference. “This whole thing about changing history for some reasons that are just now in somebody’s mind, that something was wrong that wasn’t wrong 30 years ago or 50 years ago, is not a reason to change the name of a building.”

Cruz echoed the Iowa Republican in decrying efforts to “sanitize history,” as he put it. “The journey of the United States has been a steady journey toward freedom. It has been an imperfect journey to be sure but the radicals who want to erase George Washington and Thomas Jefferson from our nation’s history fundamentally disagree with our founding principles and I count myself alongside those, like the great Frederick Douglass, who understood that our founding principles lead inevitably toward liberation,” said Cruz, whom McCain despised so much he nicknamed the Texas Republican “wacko bird” to Senate colleagues.

Republican Senators Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia, Bill Hagerty from Tennessee, and Tommy Tuberville from Alabama told The New Republic that they hadn’t given the matter any thought, while Senator Mitt Romney indicated a degree of support for the idea. “McCain deserves all the recognition we can find for him,” said the Utah Republican.

Senate Democrats were generally more supportive than Senate Republicans about changing the Russell building name to honor their late GOP colleague. “I would certainly do anything to honor Senator McCain,” said Senate Majority Whip Dick Durbin. “Renaming the Russell building for him would be a great honor.” But overall, I asked 20 senators, and only six backed a name change.

McCain, a six-term GOP Senator from Arizona and a longtime tenant of the Russell building, which houses the Armed Services Committee that McCain chaired, remains an icon of public service and bipartisanship in the Senate. “McCain would be great,” said Democratic Senators Ben Ray Luján of New Mexico and Ben Cardin of Maryland, using the exact same language when asked. “I’m all in favor of John McCain having that honor,” said Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey. “I’d certainly consider it,” said Senator Bob Menendez, also of New Jersey.

The New Republic asked Senators Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff about removing their fellow Georgian’s name from the Senate office building. “Russell literally carved his name into my desk,” said Ossoff, before adding that he did not have an opinion on the building named after a literal white supremacist from his state. (Ossoff holds Russell’s seat.)

Warnock, the first and only Black senator from Georgia, a state the latest Census data shows is over 31 percent Black, was more thoughtful than Ossoff on the matter: “I think often about the fact that when I was born, Georgia was represented in the Senate by two segregationist senators,” said Warnock, referencing Russell and Senator Herman Talmadge, who once said that the proper place for Black Americans was “at the back door with his hat in his hand.”

“My office is actually in the Senator Russell’s building,” continued Warnock. “The fact the building is named for an ardent segregationist and my office is in that building speaks to the arc of American history. Every day I walk in these halls, not just in the Russell Building, I’m struck by American history, just how far we’ve come and how much further we’ve got to go. One of the things that’s great about America is that we always have a path to make it greater.”

The Senate Rules Committee, chaired by Amy Klobuchar, has direct jurisdiction over the Capitol complex, including the names of the Senate office buildings. Klobuchar could not be reached directly for comment on this story but a Klobuchar aide tells The New Republic that the proposal is not currently on the Minnesota Democrat’s radar for the committee.

For his part, Schumer isn’t giving up on renaming the building for McCain. “Senator Richard Russell, a towering figure in the Senate of his day, was nonetheless an avowed opponent of civil rights and the architect of the Southern filibuster that long delayed its passage,” said Schumer. “It’s past time we rename that building, and I can’t think of anyone more deserving of having a Senate building in his honor than my friend John McCain.”

That’s a nice sentiment, but he doesn’t seem to have a plan—or, apparently, the votes. And so one of just three Senate office buildings—the other two are named for liberal Democrat Phil Hart of Michigan and Illinois Republican Everett Dirksen, who helped pass the landmark 1964 civil rights bill. When will the Senate decide that this just isn’t a good look?

* This article originally confused Russell with Strom Thurmond, who spoke for 24 hours and 18 minutes against the Civil Rights Act in 1957.