Say goodbye to the tight labor market.

The Labor Department released the latest employment numbers on Friday, showing that 517,000 jobs were added in January and unemployment fell to 3.4 percent, a freakish 54-year low. But don’t be fooled—follow the money. Annualized monthly wage growth, mostly falling since January 2022, fell again to 3.7 percent. For now, the labor market is still tight, but it is steadily slackening, and employers have noticed.

Indeed, when I say “wage growth,” I mean nominal rather than real (after-inflation) wage growth. When you factor in inflation, wages have been falling for some time. In 2022, real private wages declined 1.2 percent, even though inflation was coming down during the second half of that year. The only good news is that since September, inflation has been falling much faster than quarterly wage growth.

In June 2021, I warned readers not to get too used to the idea that the power balance had shifted between workers and employers, as evidenced by a New York Times headline, “Workers Are Gaining Leverage Over Employers Right Before Our Eyes.” The “Great American Labor Shortage” (thus named by a June 2021 Wall Street Journal editorial) would be over, I said, in the blink of an eye.

Initially I figured that blink would last three months before deciding, no, it would last only one. So sue me, it lasted two years. Back in the summer of 2021, I figured that as governors and, later, the federal government ended the $300 weekly supplement to unemployment benefits, workers would flood back into the job market, ending the labor shortage. Instead, the shortage lingered, and lingers still. Serves me right for presuming the relationship between income support and work to be at all straightforward.

Now, though, even with freakishly low unemployment, power is shifting back toward management. “The Bosses Are Back In Charge,” announced Chip Cutter and Theo Francis in The Wall Street Journal on Thursday. As wage growth slows, hiring gets easier. Three of the top five industries (tech, autos, finance) laid off more than twice as many people in 2022 as they did in 2021. That’s a lot of walking Spanish. Yuletide firings, which tend for tax reasons to be elevated, were more numerous in December 2022 than they were in December 2021.

“There is a segment of CEOs who are like, ‘All right, I got the power back,’” PriceWaterhouseCoopers chair Tim Ryan told Cutter and Francis (adding, of course that he himself would never stoop to such Machiavellian reasoning). Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who wears his megalomania on his sleeve (if you doubt this, watch his hydrofoil video), said on a February 1 phone call with financial analysts that 2023 would be “the year of efficiency.” Cutter and Francis reported he used that word 19 times over the course of the discussion. That’s management-speak for “more layoffs.” (Meta, Facebook’s parent, already shed 11,000 workers in November.) If your boss last year told you to come back to the office, you could ignore him. If he tells you that now, you should probably do what he says.

What did the tight labor market achieve? Probably its greatest accomplishment was to lift wages for low-income workers more than it did for other groups. An August study by the Dallas Fed found that wages for the bottom 20 percent in the income distribution rose 7.7 percent during the previous two years, compared to 4.8 percent for the middle 20 percent and 3.6 percent for the top 20 percent. Indeed, according to an April 2022 report by the Economic Policy Institute, low-wage workers (in this instance, the bottom 25 to 30 percent of the income distribution) were the only workers whose wage gains beat inflation.

Some caveats are in order. A big reason wages rose so fast for the bottom 20 percent was that this group had previously suffered disproportionately from Covid-driven layoffs in 2020. And before you cheer that the top 20 percent saw proportionately fewer gains than both the bottom and middle 20 percent, note that the real driver of income inequality at the top isn’t the top 20 percent but the top 1 percent and the top 0.1 percent. Since April 2021, income growth for the top 1 percent has been 248 percent. For the top 0.1 percent, it’s been 371 percent. So don’t throw out that “We Are the 99 Percent” T-shirt just yet.

The tight labor market failed to raise the labor share of income relative to capital, according to EPI’s Josh Bivens; rather, it fell, as corporate profits reached record highs. With corporate profits finally tumbling back down to earth, Bivens sees an opportunity for the labor share of income to grow over the next year or two, provided the Fed takes its foot off the brakes. Although the Fed is scaling back its rate hikes, there’s no chance it will actually end them soon enough for that to happen.

Still, as the tight labor market sails into the sunset, the likelihood improves that the Fed will guide the economy into a so-called “soft landing,” which is to say that the Fed’s inflation fighting won’t bring on a recession, as usually happens. The likelihood will diminish that your boss will lay you off.

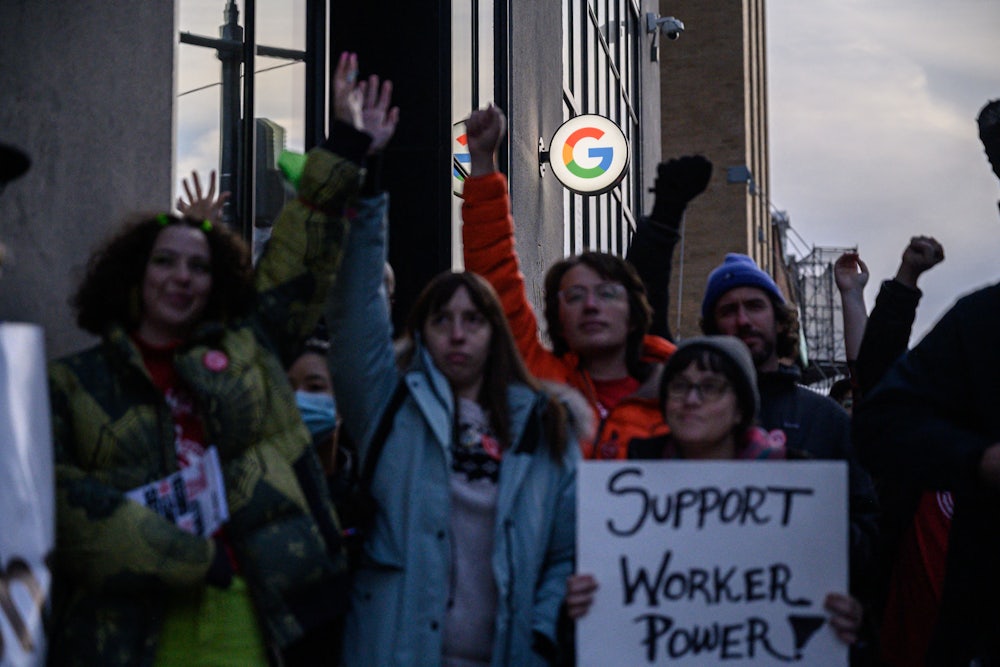

But the basic geometry of worker-management relations won’t have changed. Last month, the Labor Department reported that the proportion of U.S. private-sector workers who belong to labor unions fell in 2022 to 6 percent. It has never been lower. This is happening even as public approval of unions is at a 57-year high—indeed, about where it stood in the late 1930s. People like unions in theory, but they aren’t joining them. If you want workers to have power—real power, not a 20-month respite from employers keeping their feet on their necks—call Kevin McCarthy and tell him to forget that nonsense about cutting woke military spending and creating a national sales tax and resolutions condemning socialism “in all its forms,” and bring the Protecting the Right to Organize Act to the floor. If he says no, ask him how Republicans can keep a straight face when they say they’re becoming the party of the working class.