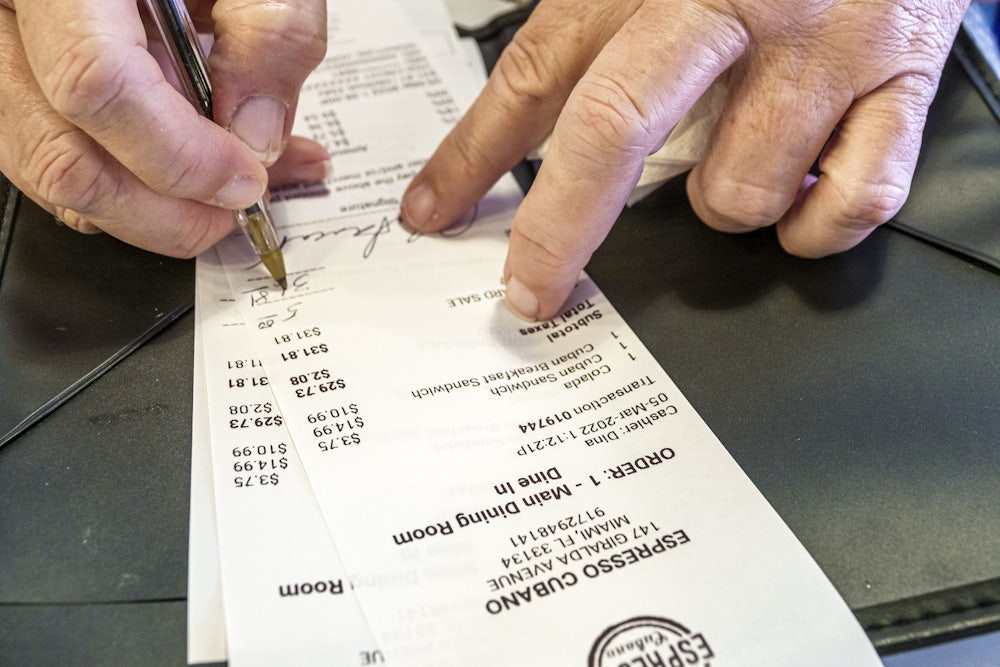

The tip economy is expanding, and some indeterminate number of consumers doesn’t like that. A January 23 Associated Press report observes that the ubiquity of tip screens has turned what once was a voluntary transaction into a quasi-compulsory one. Customers at retail food establishments are now invited routinely to choose what amount or percentage of their purchase should be added for a tip, even when they’ve received no table or counter service. If you don’t want to tip, you no longer have the option of ignoring the tip jar by the register or shrugging because you’re out of singles. You must acknowledge your stinginess by affirmatively clicking “No Tip” before the register sucks money electronically from your credit card or debit card or iPhone.

The business magazine Fast Company rather ingeniously named this phenomenon “guilt-tipping” in 2013. (Guilt-tripping—get it?—minus the r.) Ten years later, the AP reports, “many say [guilt-tipping] is getting out of hand,” although the AP doesn’t document how many people say that. Neither did similar pieces in The New York Times last April or on CNN in December. So it’s hard to say whether we’re talking about a few grouches on TikTok (looking at you, antidietpilot) or an incipient haut bourgeois uprising.

If it’s the latter, they need to calm down.

Guilt-tipping is a social good because it expands the incomes of retail employees, full stop, period. And not just in places that sell food. Digital tipping is also routine now in ride-shares and taxis, in hotels, and in app-based services like CleanCloud, which picks up and drops off your laundry. During the early days of the Covid pandemic, this combination of convenience and unavoidability, along with humanitarian sympathy for front-line workers, boosted the median tip percentage at fast-food restaurants from 19.73 percent in February to 22.22 percent in April, according to Square, the digital financial services company co-founded by Jack Dorsey. There’s some data suggesting tips got stingier and less frequent as the pandemic wore on, but that’s a matter of dispute among the experts. The larger point is that until a few years ago, it never would have occurred to most people to tip fast-food workers or dry cleaners at all.

One thing I particularly like about guilt-tipping is that it’s manipulable. In classic Cass Sunstein (or do I mean Ivan Pavlov?) fashion, you can increase tips just by increasing the percentage or dollar amounts offered as choices on the tip screen. A 2020 study of an unnamed dry cleaner app found that, at least within the range of $2 to $15, or 5–25 percent, recommending larger tip amounts did not alter spending, customer satisfaction, or repeat business. It just increased tips. Think of it as a sort of algorithmic labor theory of value.

But before you get too smug, lefties, please note which geographic locales tip most and which tip least. You’d think people in blue states would tip better than people in red states because they’re wealthier and more liberal. You’d be wrong. An August survey by Toast, another digital financial services company, showed that among the top 10 tipping states (according to average tip percentage), only one, Delaware (20.7 percent), was blue. Coming in first, second, and third were Indiana (21 percent), West Virginia (20.8 percent), and Ohio (20.7 percent). Wyoming (Wyoming!), New Hampshire, and South Carolina all made the top 10. Maryland, which has a higher median income than any other state, ranked twenty-fifth (19.6 percent). Massachusetts, land of Kennedys, which has a higher median income than any other state except Maryland, ranked thiry-sixth (19.2 percent). New York ranked forty-seventh (18.5 percent), and California ranked dead last (17.5 percent). Liberals are really cheap!

Maybe people tip more in red states because the hourly minimum wage there tends to be lower. Indiana’s minimum wage is $7.25, just as stingy as the federal minimum wage, which Congress hasn’t voted to raise since George W. Bush was president. West Virginia’s hourly minimum is $8.75. By contrast, Maryland’s minimum wage is $12.50, Massachusetts’s is $15, New York’s is $14–$15, depending on where you are and how big your company is, and California’s is $15.50. This is not to excuse the blue states, which ought to match their higher minimum wages with more generous tipping. But certainly guilt-tippers in red states have more to feel guilty about when they see the tip screen.

Giving hourly workers a higher base salary is a better way to compensate them than tipping. For one thing, a lot of employers use tips to reduce how much they pay in wages. This is actually enshrined in federal labor law, which allows employers to pay a lower “tipped” minimum wage of as little as $2.13 per hour. In effect, such employers say to their customers: “You like my employees so much? You pay them. I’ve got better things to do with my money.” Which is annoying to the customer and leaves the hourly worker without a reliable income stream. Also, there’s something distastefully seigneurial about the traditional social contract between the tipped and the tipper, where the latter says, in effect: “You give me good service, peasant, and I’ll reward you with a nice tip.” Ugh.

One thing I really like about guilt-tipping is that it severs this traditional connection between service and tip. When I buy a loaf of bread at my local gourmet emporium, I pay 20 percent at the register not because the person who handed me my bread or rang it up did it especially well but because working there doesn’t pay much and this way they earn a little more. I dispute the Emily Post Institute’s ruling that there’s no obligation at all to tip for takeout (which I was tipping for, incidentally, long before the advent of tip screens). As a general proposition, etiquette rules are a poor substitute for ethical principles. You should tip the guy even if he’s an hour late.

Still, it seems to me that if you’re a believer in economic equality you should hope, as I do, that the United States eventually becomes a society where nobody gets tipped much because a labor union already ensures that the worker in question is paid decently and the government minimizes the number of life essentials that the worker has to pay for. In the Netherlands, where the annualized minimum wage is about $26,000, nobody expects much of a tip because that’s built into the price. It’s the same in France (“service compris”) and Germany, where the annualized minimum wages are about $23,000 and about $25,000, respectively. But here in the U.S., only 6 percent of all private-sector workers are unionized, and almost none of them are minimum-wage workers. The annualized minimum wage here is about $15,000. That’s lower than in most of the other advanced industrial nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. It’s lower than in Slovenia and Poland.

Maybe someday the U.S. will become a service compris society. It’s something we should strive for. But in the meantime, we’re a guilt-tip society. Try to have the grace not to gripe about it.