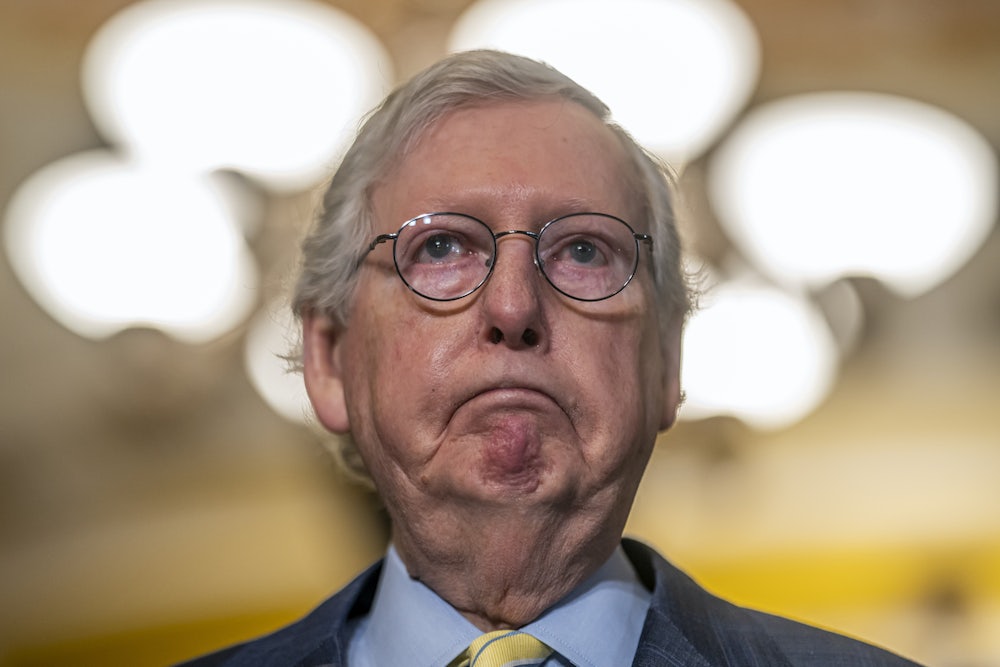

As the 118th Congress convened, public attention understandably

focused on the spectacle in the House of Representatives, as Kevin McCarthy

struggled through four days and 15 rounds of voting before winning the votes to

succeed Nancy Pelosi, the iconic Democratic speaker. But across the Capitol,

Mitch McConnell quietly celebrated a historic accomplishment: becoming the

longest-serving Senate leader in history, surpassing the record of 16 years

held by Mike Mansfield, Democrat of Montana. Mansfield will never match the

fame of his predecessor, Lyndon B. Johnson, Robert A. Caro’s “master of the

Senate.” But McConnell, a keen student of Senate history, called Mansfield the

Senate leader he most admired, “for restoring the Senate to a place of greater

cooperation and freedom.”

Unfortunately, McConnell has ignored every lesson from Mansfield’s leadership. Mike Mansfield took the helm of a struggling Senate trying to overcome the reactionary power of the Southern bloc and led it to its greatest period of accomplishment ever in the 1960s and 1970s. Mitch McConnell took a struggling Senate trying to overcome the centrifugal forces of our increasingly divided politics and drove it into an accelerating downward spiral, culminating in 2020 and early 2021 in the Senate’s most catastrophic failure, when it failed to convict Donald J. Trump in his second impeachment trial even after he incited the January 6 insurrection. In every respect, McConnell has been the anti-Mansfield.

Mansfield, born in 1900, a professor of Asian history and a World War I veteran who served in all three branches of the military, was an unlikely politician: laconic, intellectual, and averse to self-promotion. He didn’t seek to be a Senate leader, accepting the job very reluctantly at the request of his close friend, President-elect John F. Kennedy. He failed to inspire confidence initially, to the point that he offered the Senate his resignation near the end of his third year if it was unsatisfied with his light-touch approach to leadership. “It is unlikely that [Mansfield] twisted one arm in his sixteen years in charge,” Tom Daschle and Trent Lott, Senate leaders between 1996 and 2004, would later write in admiration and amazement. Yet after the assassination of President Kennedy, Mansfield built a Senate based on trust and mutual respect, enabling the body to meet the challenges of a turbulent period in a bipartisan way.

Universally admired for his wisdom, honesty, and fairness, Mansfield worked with President Johnson and the Senate led by Hubert Humphrey and Everett Dirksen to break the Southern filibuster to pass the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964. Drawing on his deep knowledge of Asia, Mansfield presciently warned Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon that the U.S. engagement in Vietnam was disastrous. Under his leadership, the Senate became the forum for challenging, and ultimately ending, the war.

In October 1972, when Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered the abuses of Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign, Mansfield immediately promised a full and fair Senate investigation. When the Senate convened in January 1973, it unanimously voted to create a select committee to investigate the abuses, by then known as “Watergate,” even though Nixon had won reelection in a 49-state landslide. The bombshell revelations of the committee’s memorable hearings in the summer of 1973, led by Democrat Sam Ervin and Republican Howard Baker, paved the way inexorably to Nixon’s resignation a year later.

In contrast, McConnell has been far and away the most partisan Senate leader in the modern era. Passing up virtually every opportunity to turn down the heat and bring people together in a bitterly divided nation, McConnell labeled his opponents “thugs” and “the mob”; blasted “blue state bailouts” during the pandemic; silenced Elizabeth Warren with an unprecedented misuse of the Senate rules; accused Democrats of “treating religious Americans like strange animals in a menagerie”; admitted openly that “the single most important thing” he and Republicans could do was to make Barack Obama a one-term president; and opposed the nomination of Judge Ketanji Jackson to the Supreme Court, calling her “the favored choice of left-wing, dark money groups.”

Early in his Senate career, McConnell set his sights on being the leader; with great patience and political skill, he achieved that after 22 years in the Senate. Yet despite his supposed love of the institution, McConnell has routinely trashed the customs and norms essential for the Senate to serve as what Walter Mondale called “the nation’s mediator.” There is no precedent for McConnell’s relentless efforts in 2017 to repeal the Affordable Care Act without a replacement—and without hearings, committee markup, consultation with affected interests, or any trace of bipartisanship. Nor was there any precedent for his refusal to give Judge Merrick Garland, President Obama’s nominee for the Supreme Court, a confirmation hearing for nine months before the 2016 election.

In stark contrast to Mansfield, McConnell failed America in crisis times. He did not use his power to stop Donald Trump’s assault on our democracy. He was AWOL when Trump’s unhinged leadership during the pandemic caused hundreds of thousands of Americans to die needlessly. He did not counter Trump’s claims that the presidential election was stolen for five long weeks after the Associated Press and networks called the election for Biden, allowing the “Big Lie” to spread like wildfire and to be embraced by 50 million Americans. McConnell could not bring himself to vote to convict Trump in his second impeachment trial, even after the January 6 insurrection, despite his powerful denunciation of the former president.

Interestingly, McConnell has forged an impressive record in the past year: steadfastly supporting President Biden’s strong position on sending arms to Ukraine, breaking with the NRA and the gun manufacturers to support the first gun safety legislation since 1994, and joining with Democrats and Republicans to pass the Electoral Count Act and fund the government through September 30, 2023. Politicians operate at the intersection of conviction, calculation, and conscience, and perhaps in McConnell’s case, some degree of regret and guilt. As long as he still holds power, McConnell can airbrush his record by doing some good for America.

Ultimately, however, McConnell’s page in the history books is likely to focus less on his failure to stop Trump and more on how an iron-willed leader orchestrated a corrupted confirmation process for four years to produce a radical, lawless Supreme Court. When the Republican Senate finished the job in October 2020 by ramming through the confirmation of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to fill the vacancy left by the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg eight days before Election Day, McConnell congratulated himself on “the single most important accomplishment of my career.… A lot of what we have done in the last four years will be undone sooner or later by the next election. They won’t be able to do much about this for a long time to come.”

By “they,” McConnell meant future presidents,

Congresses, and American voters—an appalling statement for a political leader

in a democracy. McConnell’s legacy is assured; now 80, he will be recalled

every time his illegitimate, extremist court diminishes the constitutional

rights of Americans or usurps the authority of other branches of government.