It was a late afternoon in mid-November, with the nip of early winter in the air, when I visited the Russell Senate Office Building to meet with Vermont Senator Pat Leahy in his spacious yet surprisingly intimate office, with a sofa and chairs arranged near the fireplace. An aide squatted down beside us to add another log to the fire. Leahy’s wife of 60 years, Marcelle, joined us, carrying a large bouquet of flowers. The couple still convey a strong sense of the people they were in the early years of their marriage—he a small-town lawyer, she a nurse at a local hospital. Leahy showed off photos of their three children and five grandchildren. “I’m not someone who wants to hang the walls with photos of 50 great and famous people I’ve known,” he said. “I’d much rather be surrounded by pictures of family.”

Leahy, who entered the Senate in 1975 and leaves it after 48 years in January 2023, is the body’s longest-serving sitting member. To most Americans, he is probably best known for his decades on the Senate Judiciary Committee and his opposition to the drive by conservative activists to transform the federal courts into an instrument of their ideological agenda. But I’d come to talk to him about something different, something that rarely if ever makes the cable news circuit: the war in Vietnam, the wounds it had left, and the part he had played in healing them. He’s never seen this as a partisan issue, just a matter of simple human decency, being one of those, like Joe Biden, who mourn a lost era of comity in the Senate, in which political adversaries could still reach with respect across the gulf of their disagreements. His work in Vietnam has always been underpinned by that vision, and I wanted to ask him whether, in our current divided state, he could imagine it continuing after his retirement from the Senate at the age of 82.

Vision alone doesn’t get you far in Washington. It has to be turned into legislation, and legislation into dollars and cents. In addition to his role on the Judiciary Committee, Leahy also chairs the Appropriations Committee, which is where the purse strings are untied, and, as he wrote in his recently published memoir, The Road Taken, “few people really ever sifted through the line items to understand what we were doing was actually making American foreign policy.” It’s also why you can’t talk about his work in Vietnam without also talking about his senior aide, Tim Rieser, who has been with him since 1985, and who will retire from his current role in January. Despite his bland-sounding job title—Democratic clerk for the Appropriations Subcommittee on State and Foreign Operations—Rieser has been the master of its arcane mechanics. “A dog with a bone,” Leahy calls him. Given a problem to solve, “He would not stop until every last drop of marrow and morsel of sinew had been licked clean.”

Since 1989, as the United States and Vietnam were taking their first baby steps toward reconciliation, Leahy and Rieser have channeled hundreds of millions of dollars in aid to Vietnam, forcing the United States to take responsibility for what former Senate leader Mike Mansfield once called the “great outflow of devastation” from the war: the bodies broken by unexploded bombs; the lives blighted by exposure to Agent Orange; the ongoing threat from “hot spots” contaminated by dioxin, its toxic by-product; and now, at last, some long-overdue aid to help Vietnam recover and identify the remains of its war dead. In the process, they have built the scaffolding of a new relationship, in which bitter enemies, in one of the stranger twists of geopolitics, have been transformed into close working partners and military allies.

Leahy and Rieser have faced no small number of obstacles along the way. For many years, embittered American veterans and recalcitrant anti-Communists in Congress opposed any hint of reconciliation with Vietnam. Progress was often slowed by suspicions on the Vietnamese side and by cumbersome bureaucracies in both governments, and State Department and Pentagon lawyers remain wary to this day of any humanitarian effort that implies an admission of liability. But as Rieser often says, when you run into an obstacle, you redefine it as a problem to be solved, and that process starts with all parties identifying their common interest in finding a solution. There are always common interests; you just have to look for them.

On January 27, Vietnam will celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords, which led, two months later, to the withdrawal of the last American combat troops. Yet the fighting was not over. The Saigon army fought on, entirely dependent on new infusions of military aid from the United States, and this in turn depended on the approval of the Senate.

Of all the “Watergate babies” elected in the 1974 midterms, Leahy, a 34-year-old state’s attorney for Chittenden County, Vermont, was one of the unlikeliest. Vermont, odd as it may seem given the state’s leftish politics today, had never elected a Democrat to the Senate, and its political establishment and leading newspapers were unswerving supporters of the war. Yet Leahy eked out an improbable victory. (Trailing in third place was an equally young civil rights activist, Bernie Sanders, running under the banner of the Liberty Union Party.)

Leahy had always opposed the war. In May 1970, he marched with protesters against Nixon’s secret bombing of Cambodia and the killing of four students at Kent State University in Ohio. Now, as the youngest member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, he could do something more concrete to end the conflict. The 15-member committee faced a crucial vote on April 17, 1975, to consider President Gerald Ford’s request for $215 million in new military aid to “stabilize” the government of South Vietnam. Leahy described to me the pressure that was brought to bear on him—a personal call from the president, a hard-sell visit to his office by Henry Kissinger—but he stood firm. The committee rejected Ford’s request by a vote of eight to seven. Thirteen days later, the Saigon government collapsed.

The war left innumerable scars. Each had to be confronted in turn, and the United States, despite its defeat, had the power to dictate the sequence. For Americans, the nearest thing to a happy ending to a lost war was Operation Homecoming, the return of 591 prisoners freed under the Paris Agreement. But another 2,646 men were left behind, missing in action, and Washington made it clear that, until Vietnam cooperated in the “fullest possible accounting” of their fate, there could be no talk of any other issues, least of all the infinitely greater numbers on the Vietnamese side.

After a decade, however, it became clear that Washington’s hard line, with a punitive trade embargo, was doing nothing to bring the MIAs home. Vietnam, ravaged by the war and the failure of Soviet-style five-year economic plans, embarked on a program of reforms in 1986, desperate for foreign investment, and U.S. corporations were eager to get in on the act. With both sides now seeing a common interest in cooperation, joint U.S.-Vietnamese military teams began to scour remote airplane crash sites, which accounted for the majority of the MIAs.

The searches built a first measure of trust between the two countries, and the sequel to trust is reciprocity. For Leahy, the first glimmering of a plan came on a congressional visit to Central America in 1988, another Cold War battlefield where civilians once again were the collateral damage.

It’s a story he tells often. In a remote refugee camp near the Honduras-Nicaragua border, he encountered a skinny 10-year-old Miskito Indian boy limping around on a crude wooden crutch. He had lost a leg to a land mine. Who had planted it? The Contras? The Sandinistas? The Honduran military? To Leahy, the question was beside the point. All that mattered was to get kids like this some help. A young embassy official shook his head; there was no provision in the budget for prosthetics. But by now Leahy was a senior member of the Senate Subcommittee on Foreign Operations, and crafting such provisions would turn out to be the particular talent of his recently appointed aide, Tim Rieser.

Rieser was a fellow Vermonter. He turned 18 in 1970, considered registering as a conscientious objector, but in the end avoided the draft by drawing a high lottery number. After law school, he spent a decade as a public defender until he joined Leahy’s team as a volunteer. In 1985, he came on board full-time as a staffer on the Judiciary Committee, dipping a toe into foreign policy issues like war and human rights in Central America. In 1989, his boss became chairman of the Appropriations Subcommittee, and Rieser’s course was set.

Although the Patrick J. Leahy War Victims Fund, created in that year, would eventually direct humanitarian aid to more than 30 countries, it started with Vietnam. “What we did there was so outrageous,” Rieser said. “The Vietnamese did nothing to us, and we practically destroyed their country, lied about it, killed countless people, and nobody was ever held accountable. To be able to do something about it has been really fortunate for me.”

A lot of that “something” has depended on the close relationship between Leahy and Rieser and American veterans who returned to Vietnam with two simple questions: What do you need? and What can we do to help? The most prominent of the antiwar vets was Bobby Muller, a Marine who used a wheelchair after taking a bullet in the spine on the edge of the Demilitarized Zone that separated North and South Vietnam. He understood that, with emotions still raw in Congress and among many veterans, any gesture of goodwill had to be purely humanitarian, with no hint of sympathy for Vietnam’s Communist government, with which Washington still had no diplomatic relations.

Muller came to see him one day, Leahy said, leaning forward to imitate the Long Islander’s famously in-your-face style. “Senator, we gotta get rid of land mines! So he gave me 22 reasons why we should do that. I said, don’t worry, I’ve seen it, I’m all for it, so let’s put something together.” That marked the birth of the War Victims Fund, a practical way of aiding people like the kid in Honduras, replacing their crude crutches and makeshift artificial limbs with modern prosthetics, orthotics, and wheelchairs. “The State Department was reluctant,” Leahy said, “so I went down to see [President] George H.W. Bush, and he thought it was a pretty good idea.”

The first $1 million went to Muller’s Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation, which created a prosthetics center at the Olof Palme Institute in Hanoi, the country’s best pediatric hospital, later expanding it to Bach Mai Hospital, which had been badly damaged during Nixon’s 1972 “Christmas bombing” campaign.

Leahy went to Vietnam for the first time in 1996, following the normalization of diplomatic relations. Giving his fellow senators a close-up view of the human consequences of the war would be a transformative experience, he believed. One member of the delegation was the former astronaut John Glenn. “Here I am, six foot plus, 200 pounds, and I’m lifting this little Vietnamese guy into his fuchsia-colored wheelchair, and he pulls me down and kisses me,” Leahy recalled. “And there’s John Glenn, a guy who orbited the earth and knew that his spacecraft could have burned up, a guy who never showed emotion, and there were tears in his eyes.”

But Leahy knew that the demand for artificial limbs and wheelchairs would continue unless the underlying cause of so many of the injuries was dealt with, and this was the next door to be unlocked. In 1992, he had successfully introduced a law banning the export of anti-personnel land mines, but his subsequent efforts to restrict the use and export of cluster munitions foundered. The argument is that cluster bombs are different, he said, because “unlike land mines, they are not intentionally designed to be triggered by the victim”—a distinction likely lost on those who were stepping on them. Tens of thousands of Vietnamese and Lao had lost limbs, eyes, and often their lives to cluster bombs, which were notorious for their frequent failure to detonate on impact. “I did include a prohibition on the export of cluster munitions with a failure rate of more than 1 percent,” he said, “but the Defense Department was always strongly opposed.” It was one of his greatest disappointments.

The most practical step was to clear the areas that were still contaminated, starting with Vietnam’s tiny Quang Tri province. The tonnage of bombs the United States dropped on Southeast Asia is hard to wrap one’s head around: It was three times greater than in all theaters in World War II. Quang Tri, immediately south of the DMZ, was the worst affected area. Roughly the size of Delaware, it was bombed more heavily than the whole of Germany. It suffered grievously during Hanoi’s two biggest military offensives—during Tet, the Lunar New Year, in 1968, and then again in 1972, when the People’s Army of Vietnam, or PAVN, launched a full-out assault across the DMZ, using tanks and heavy artillery, to which the United States responded with waves of B-52 strikes and naval shellfire.

Like the earlier prosthetics program, the effort to make Quang Tri safe began with American private citizens. The first to arrive were members of a small group from Washington state, PeaceTrees, accompanied by a veteran of military intelligence, Chuck Searcy, who was running Muller’s program in Hanoi. By the time Bill Clinton vowed, during his November 2000 visit to Hanoi, “to work with Vietnam until every bomb and mine is cleaned up, no matter how long it takes,” several European and American demining groups had arrived in Quang Tri, and in 2001 Searcy, partnering with an energetic young provincial official, set up one of the best-known of them, Project RENEW.

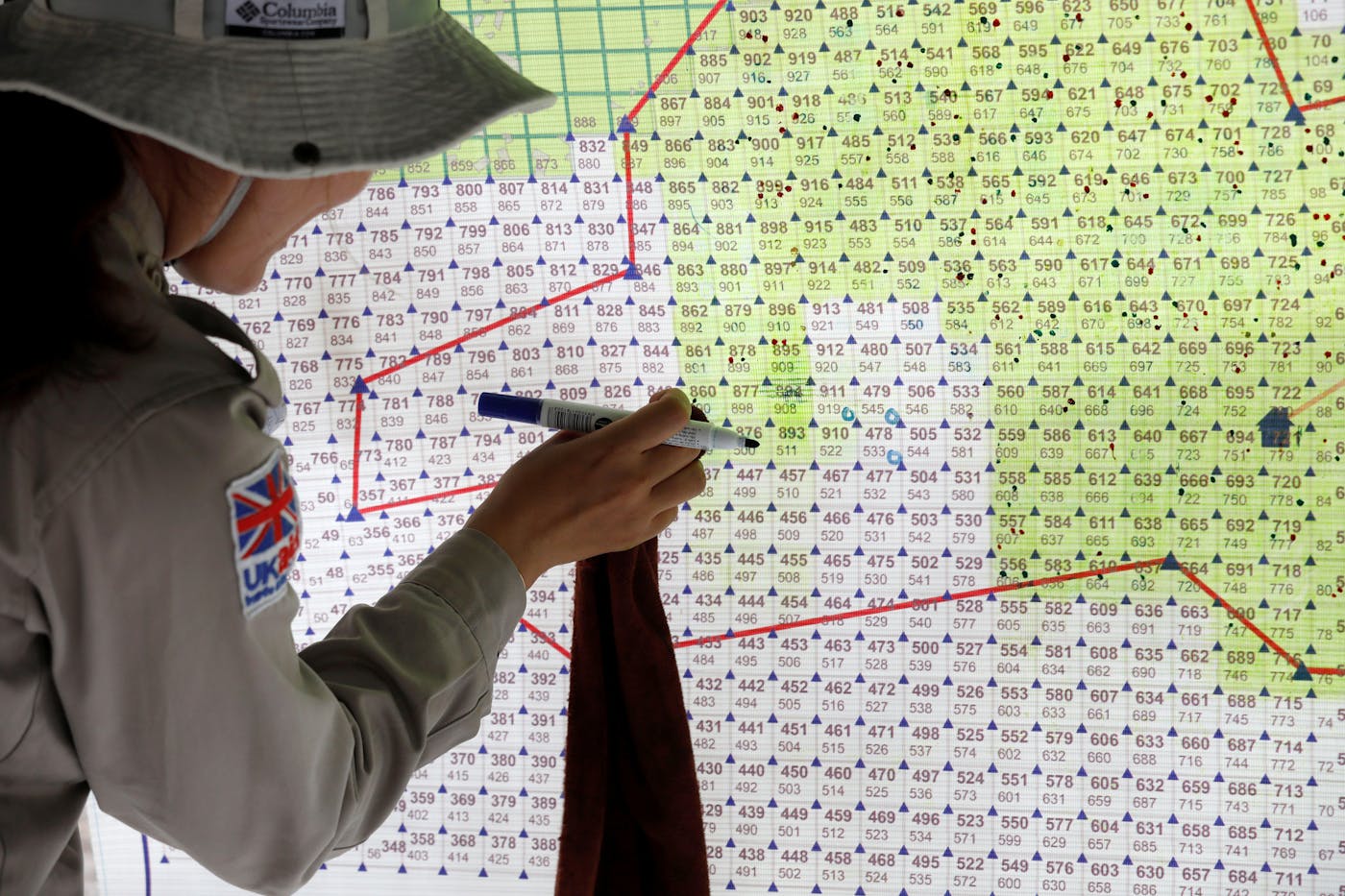

The U.S. Air Force provided maps of every bombing raid it had carried out over the province, pinpointing the areas of greatest ongoing danger, and in 1996 the State Department offered the first official funding for demining equipment, a modest $3 million. Senior Vietnamese military officers were wary, but Searcy assured them that there were no strings attached. Since then, Washington has contributed almost half a billion dollars to operations to clear unexploded ordnance from Quang Tri, two adjacent provinces, and border areas of neighboring Laos. By 2022, the demining teams in Quang Tri had removed more than three-quarters of a million items, and the tiny province has become a global model for how countries ravaged by war can be made safe again.

What remained was the most intractable of all the legacies of the war: Agent Orange. Since the late 1960s, Vietnamese doctors had been documenting the high incidence of often grotesque birth defects in defoliated areas of the South and in the offspring of veterans returning home, who were also suffering from alarming rates of cancer. Yet it was impossible—and still is, despite decades of research—to prove cause and effect.

Even American vets had to fight for years before the government acknowledged, with the 1991 Agent Orange Act, that there might be an association between their service in Vietnam and a list of conditions that has steadily expanded to include common diseases like prostate cancer and Type 2 diabetes. The act was more the result of political pragmatism than hard science, combining the best available data with basic humanitarian decency and a good measure of guilt. The United States had treated its Vietnam veterans poorly, and they deserved, at the very least, the benefit of the doubt.

“After the V.A. started paying out benefits to American veterans, the double standard was obvious,” Leahy said. Vietnamese scientists were written off as crude propagandists and extortionists. Even after diplomatic relations were normalized in 1995, the subject was a political third rail. Ted Osius, who served as ambassador to Hanoi during the Obama administration, recalled going to a conference as late as 2002, when he was the State Department’s regional science officer for Southeast Asia, and being instructed not to use the wordsAgent Orange or dioxin in public.

One of the biggest challenges was the sheer scale of the defoliation campaign. Twenty million gallons of herbicides were sprayed on the former South Vietnam, and one-sixth of its land area might still be contaminated; as many as 4.8 million people might have been exposed; Vietnam had hundreds of thousands of cases of disabilities that might plausibly be connected to Agent Orange. How could you get a handle on a problem of that magnitude?

A joint team of Canadian and Vietnamese scientists gave the first answers with a report, issued early in 2000, on dioxin contamination in the A Luoi Valley, a heavily sprayed area on the border with Laos. This found that most of the dioxin in the environment had long since dissipated. The ongoing risk was confined to former U.S. military installations, such as the old Special Forces base in the valley, where the chemicals had been stored, loaded onto aircraft, and spilled. Once these “hot spots” were identified, cleaning them up became a manageable problem.

The report also showed conclusively how the dioxin in Agent Orange moved up through the food chain, especially via the fish that local villagers raised in ponds that had formed in old bomb craters. From there it migrated into the human body, its concentration steadily increasing in fatty tissue, to be transmitted to the next generation through breast milk.

The study changed the debate, yet it took several years to answer the questions it raised. Where were the hot spots? Funded by Charles Bailey, head of the Ford Foundation’s Hanoi office, the same Vietnamese-Canadian team determined that the worst contamination remained at the big air bases in Danang, in central Vietnam, and Bien Hoa, 20 miles from Saigon. Both were in densely populated urban areas, posing a clear and present danger to local residents.

Cleaning up these bases would be enormously expensive, but it was the kind of thing the United States did best: large-scale, technologically sophisticated, with the promise of eventually declaring mission accomplished. On his second trip to Vietnam, in 2014, Leahy went to Danang to symbolically light the giant oven, a squat ziggurat structure at one end of the runway, with a footprint the size of a football field, that would destroy the dioxin by superheating 90,000 cubic meters of contaminated soil and lake sediment.

This was a fine and honorable thing, a making right of past wrongs; yet for Leahy and Rieser there was a higher imperative—getting help directly to those whose disabilities and birth defects might be the result of dioxin exposure. Politically, this was a much bigger hurdle.

I talked about this in Hanoi one day with Madame Ton Nu Thi Ninh, one of Vietnam’s most experienced diplomats, who worked closely with Bailey for several years as an aid program for dioxin-related disabilities took shape. The resistance of American officials to any talk of “Agent Orange victims” had been infuriating, she said. “It was always more comfortable for the Americans to talk about the environment, but looking into the human impact—that was a much more difficult step. There are people with disabilities in all developing countries, they told me, and we help them everywhere, regardless of cause”—a phrase that State Department lawyers continue even now to insist on. “No, I told them, Vietnam is different. We never had disabilities like these before the American war. All you need to do is add just a few words—Agent Orange–impacted. Accept this at least for our civilians, if not for our veterans.”

As she said, much of the problem was a matter of language, and that was Tim Rieser’s stock in trade. In November 2006, President George W. Bush signed a joint statement with Vietnamese President Nguyen Minh Triet that touched on America’s obligation to help Vietnam overcome all of the worst legacies of the war. Shortly after he left Hanoi, Rieser flew in, accompanied by Bobby Muller, and announced a new humanitarian aid program, to be administered by USAID. This would provide $3 million for “pilot programs for the remediation of Vietnam conflict–era chemical storage sites, and to address the health needs of nearby communities.”

Rieser and Bailey worked together over the next decade to progressively tweak this language, to make sure that the money went where the need was greatest. Finally, in 2016, Rieser came up with the magic formula: The aid, which had now inched up to $7 million a year, was for “health and disability programs for areas sprayed with Agent Orange and otherwise contaminated with dioxin, to assist individuals with severe upper or lower body mobility impairments and/or cognitive or developmental disabilities.”

Ironically, it was Agent Orange, the worst of all the legacies left by the misuse of U.S. military power in Vietnam, that turned out to be instrumental in forging a military partnership between former enemies. Both countries were now alarmed by China’s new projection of power in the South China Sea, and Bien Hoa was home to a squadron of fighter-bombers of the People’s Air Force. Danang was still used as a military base as well as a civilian airport. So cleaning up the bases would not only mean previously unimaginable levels of aid; it would also need buy-in from both the Vietnamese Ministry of Defense and the Pentagon.

This was no simple matter. The Vietnamese military was a uniquely powerful institution, often difficult to work with because of its complex internal bureaucracy and lack of transparency, with a surprising amount of autonomy vested in offices at the provincial level.

“How did you get around those problems?” I asked Leahy. Personal relationships, he said without hesitation. The key, he said, was his friendship with Senior Lt. Gen. Nguyen Chi Vinh, the vice minister of defense. Just as important as Vinh’s formal role, he was the son of one of Vietnam’s most celebrated war heroes, which gave him unusual prestige. “We hit it off right away,” Leahy said. “We would trade family pictures, and he’d always hold Marcelle’s hand. She became ‘Madame Leahy,’ and he started sending me personal notes addressed to ‘Uncle Leahy,’ which is the Vietnamese way of showing respect.”

“And don’t forget Thao,” Marcelle said. “Remember our scooter ride?”

She was referring to Thao Griffiths, a longtime friend of Gen. Vinh’s, who ran the Hanoi office of Muller’s Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation—the post Chuck Searcy had once held. Although it was painful, Marcelle said, to listen to Thao’s account of America’s wartime cruelties, the two women bonded, and neither of them was much inhibited by diplomatic protocol. One day, when Leahy was off at an official meeting, all suits and uniforms and speeches, they took off on Thao’s scooter for a three-hour street-level tour of Hanoi, stopping at the lakeside monument marking the spot where Navy Lt. Cmdr. John McCain had been shot down during a bombing raid.

President Obama had promised to clean up Bien Hoa, but McCain, who had done as much as anyone to foster postwar reconciliation, proved to be a surprisingly stubborn obstacle. Danang, where the cleanup was completed in 2017, had cost roughly $116 million, but the contaminated area at Bien Hoa was four to five times larger, and the cost of its remediation might exceed $1 billion. Gen. Vinh and Ted Osius, by this time the U.S. ambassador, settled on an initial U.S. commitment of $300 million, and Osius argued that this amount, which would have broken USAID’s budget, should be split 50-50 with the Department of Defense.

McCain, who chaired the Senate Armed Services Committee, at first balked at the idea of the military funding of what he saw as essentially a humanitarian project, while Pentagon lawyers worried that it would open up the United States to claims from other combat zones. Osius pushed back, distraught, as the father of two young children himself, at the sight of kids playing in dioxin-contaminated mud when he went to see Bien Hoa for himself. “But [Secretary of State] Rex Tillerson told me to cease and desist,” he said. “He didn’t want to hear any more about it.”

Osius, unhappy with Trump-era policies, was summarily removed from his post in the summer of 2017 and resigned from the State Department shortly afterward. But Leahy and Rieser persisted. “We always wanted DoD to be involved,” Leahy said, “since they had caused the problem to begin with.” Osius gives Rieser much of the credit for breaking the logjam. “He was so stubborn,” he said. “I kept getting knocked down, but Tim just wouldn’t give up.” As Leahy said, his aide was the dog with the marrow bone.

In April 2019, Leahy traveled to Vietnam at the head of another congressional delegation, his third, for the inauguration of the Bien Hoa project. “When we put this trip together, I carefully picked workhorses, not show horses,” he told me, and the trip had the flavor of an audition for those who would pick up the baton when he retired. He insisted that the group should include Republicans, two of whom, Senators Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Rob Portman of Ohio, joined seven Democrats for the ribbon-cutting. Afterward, they drove into town for a banquet lunch, where they mingled with Vietnamese in wheelchairs, and the two governments signed an agreement on a new five-year commitment of aid, worth $65 million, which is now divided among eight provinces that were heavily sprayed with Agent Orange, with the hope, Rieser says, of adding two more.

Later, as Leahy describes in his memoir, a group of senators went to Easter Sunday Mass at Saigon’s historic nineteenth-century cathedral. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, Democrat of Rhode Island, told stories of his childhood in Saigon, where his father had been number two in the embassy after the signing of the Paris Accords. “Sheldon, I never knew that about you,” Portman said. Murkowski looked across at Leahy. “Why can’t the Senate be like this all the time?” she asked.

Leahy planned to lead one last delegation to Vietnam, just before the 2022 midterms. For the Vietnamese, it would be a red-carpet affair, a final celebratory lap of honor for the senator that would include the inauguration of a memorial peace park at Bien Hoa on a piece of land that had been successfully decontaminated.

But just nine days before the delegation was due to leave, Rieser emailed me to say that his boss had been hospitalized overnight after feeling unwell, and the trip was off. Since I’d intended to travel with them, I briefly thought of canceling my own plans, but it seemed important to go ahead, since Leahy and Rieser had pushed through a string of new projects in the past year that would put the capstone on their legacy. One of these was the first-ever aid package for presumed Agent Orange victims in Laos, after new revelations of the extent and consequences of the secret defoliation campaign in that country. Another designated funds from USAID to support the redesign of Vietnam’s War Remnants Museum, once known as the Exhibition House of American and Puppet Crimes and now one of Ho Chi Minh City’s main tourist attractions. The plan would include a permanent exhibit showing how the two countries had worked together to heal the worst wounds of the war.

But the most significant of all these new projects was a commitment—long overdue, in Leahy’s mind—to help Vietnam recover and identify its missing war dead. No one really knows how many there are, but one estimate, said Andrew Wells-Dang, senior expert on Vietnam at the United States Institute of Peace, is that 200,000 bodies were never recovered, with another 300,000 buried under headstones marked Chua Biet Ten—identity unknown. The joint searches for the much smaller number of American MIAs had been the first step in building trust between former enemies, and that story would at last be brought full circle.

The Wartime Accounting Initiative, as it’s known, is the product of an agreement signed by Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin in Hanoi in August 2021. It’s a five-year, $15 million project that involves several American and Vietnamese organizations, as well as the International Commission on Missing Persons in The Hague. It has many dimensions, including technical training, public education, and building people-to-people networks, but it boils down to two main priorities. The first, which falls primarily to Harvard’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, is to systematize the mass of data that might speed the search for the missing, which is now a matter of urgency as surviving witnesses die and human remains degrade. The second, administered by USAID, is to help Vietnam identify those remains, using state-of-the-art single nucleotide polymorphism or SNP-based genetic analysis, which produces unique matches, unlike the older mitochondrial DNA markers used by Vietnam up to now, which are common to all members of a matrilineal line. Each is a monumental undertaking.

Giang Nam Trinh, a lead researcher at the Ash Center, joined the team while doing her Ph.D. at Texas Tech University, which holds a vast trove of documentation on the war. The project had personal meaning for her, she said when we met in Hanoi: Her uncle was a frogman who disappeared in 1974, his body never recovered. Unable to bury her son with his ancestors, as custom and tradition demanded, Giang’s grandmother, like so many Vietnamese, constructed an empty “wind tomb” as a way of honoring him.

The Texas Tech collection includes the archive of the Army’s Combined Document Exploitation Center, some three million pages of declassified and digitized materials: after-action reports, command chronologies, daily journals, prisoner interrogations, defector interviews, intelligence analyses, aerial photographs, maps, and a multitude of ephemera like the diaries, letters, photographs, and other “souvenirs” picked up on the battlefield by American soldiers. Perhaps 10 percent of these documents, Giang said, might hold clues to burial sites, and in theory these could be correlated with Vietnam’s own records. But a new generation of digital technology, perhaps aided by artificial intelligence, would be needed, not least because current search tools can’t account for the multitude of diacritic accents in Vietnamese: The tonal variants on a simple word like ma, for example, may give it half a dozen different meanings.

Independent research by veterans promises to be an important part of a future open-source database. Bob Connor, who served at Bien Hoa as a sergeant in the Air Force police, told me that when the 1968 Tet Offensive began, he was on duty atop the tall guard tower at the base, giving him an unobstructed view as a large force of Vietcong stormed the eastern perimeter. Helicopters and fighter jets made short work of them with machine guns and napalm, and, when it was over, the bodies were shoveled into a mass grave.

Connor didn’t think much about the war after he came home, until one day in 2016 his granddaughter called to say she had to do a high school project about Vietnam. Did he have any suggestions? Out of curiosity, he logged on to Google Earth to see if looking at the layout of the base might trigger any memories. At that time, Google had a crowdsourcing feature called Panoramio, which allowed users to augment maps with their own images and messages, so Connor posted a note with his email address, saying that he had information about a mass grave.

To his astonishment, one thing led quickly to another: a message from a PAVN veteran, who put him in touch with a retired colonel, and a collaborative network was born. The grave site turned out to be just 20 yards from the location Connor had pinpointed. There were 150 bodies, of which 72 were identified and returned to their families for a proper burial. Other vets came forward with stories of more mass graves around Bien Hoa and the neighboring base at Long Binh, one of which, Connor said, contained 673 bodies. His best guess, he told me, was that the leads provided through this network might eventually help Vietnam locate as many as 8,000 of its fallen soldiers.

At his modest home in the western suburbs of Ho Chi Minh City, I met Dr. Tran Van Ban, a 78-year-old veteran of the PAVN. He grew up in the northern port city of Haiphong, enlisting with 28 other young men from his commune, literally signing his name in blood. They swore an oath to one another: Many of us will not return. If I should die, one of you must bring my body back to my mother.

In November 1967, they set out on the arduous six-month trek down the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos and Cambodia, under constant U.S. bombing. After crossing into Vietnam, his battalion, part of the PAVN’s 268th Regiment, pressed on to the so-called Iron Triangle, a critical war zone that threatened the western approaches to Saigon. “We were facing elite American units,” Ban said. “The 25th Infantry Division, which they called Tropic Lightning, the Big Red One, and the Marines. They had three huge bases, each with its own airstrip. They had tanks, heavy artillery, helicopters, B-52s, ‘bunker buster’ bombs.”

The consequences were devastating. “My battalion had 653 men,” he said. “By the time of Liberation, 121 were still alive. Of those, 80 were affected by their exposure to Agent Orange, and 55 had children with birth defects. Of the 29 from my commune, four survived.” There were now 500 graves in the local martyrs’ cemetery, he said, but 300 of them were wind tombs.

Ban himself was left for dead on the battlefield, and his family didn’t know that he had survived, badly wounded, until he returned home after the war. Assigned to a clandestine field hospital, he was given the task of keeping casualty records. He drew dozens of detailed maps of burial sites and came up with the idea of writing the name of each dead fighter on a slip of paper, sealing it up in an empty medicine vial, and placing it in the corpse’s mouth for later identification. He lost all his records one day in an air raid, but, blessed with a near-photographic memory, he set about reconstructing everything from scratch.

When the war was over, he went to medical school and worked as a general practitioner until his retirement. But he always pursued a parallel mission, honoring the oath he and his comrades had sworn to one another. He compiled the full enlistment rosters of many communes in Haiphong and returned year after year to the old battlefields to search for graves. Although much of the landscape had changed beyond recognition, he looked for remembered landmarks: a water well that was still in the same place, traces of a coal fire that might once have been a field kitchen.

His maps turned out to be remarkably accurate. “I’ve recovered the remains of 14 of the 25 who died from my commune and returned them to their families,” he said, “so that leaves 11 I still have to find.” His reports to local authorities have located “maybe 50 or 60 percent of our other fallen friends.” He showed me a photograph of a common grave in the main martyrs’ cemetery in Ho Chi Minh City, where 25 of these soldiers are buried. But their bones were jumbled together and had never been submitted to DNA analysis. “People think I must have some kind of supernatural powers, or maybe I’m a psychic,” he said, “but I tell them, no, it’s all because of my heart, and having a good memory.”

I asked him what had happened to his records. He went into another room and came back with a stack of school exercise books, filled with field notes; photo albums with detailed captions; sheaves of hand-drawn maps. He knew that veterans in other areas were doing similar work, but he had no idea if anything like this huge personal archive existed anywhere else in Vietnam.

I asked if he’d heard about the new Wartime Accounting Initiative; this was precisely the kind of material they were looking for. He looked at me for a moment in apparent disbelief and then choked up. “Please tell them I would like to help,” he said when he eventually composed himself. “This is my sacred mission. These things haunt me, when I’m sleeping, when I’m eating, they are always in my mind.”

More than 1,000 of the American MIAs in Southeast Asia have now been recovered, and each of the 1,582 still missing has his own detailed dossier, regularly updated with full reports on every search mission and witness interview. The Vietnamese, for the most part, must rely on their own limited resources. I visited several families, including two who are now working with the Wartime Accounting Initiative, and in each case the search had taken them back to the singular devastation of Quang Tri province.

Losing a loved one and failing to recover the body bring a unique kind of prolonged grief, which both Americans and Vietnamese have coped with according to their own customs. In Vietnam, a body must be laid to rest with its ancestors, and there are elaborate mourning rituals to observe; otherwise, the dead risk becoming unquiet “wandering souls.” In the austere postwar years, the government discouraged these practices as outmoded superstitions, but they have proved stronger than party dogma. Many people seek the help of psychics, like a family I met in Hanoi, who credited them with tracking down their son in an unmarked grave in Quang Tri. Now the surviving brother wanted to exhume his remains for DNA analysis, but his 86-year-old father resisted. What if it turned out to be a case of mistaken identity?

Others have found comfort, however, in the certainty provided by DNA analysis. Nguyen Thi Chin lives in the small town of Thach That, west of Hanoi. Like so many Vietnamese homes, hers is dominated by an ornately carved family altar, with portraits of her late mother and her two lost brothers, fresh-faced teenagers, framed by oil lamps, large bowls of apples and persimmons, and blue-and-white porcelain vases crammed with burned-out incense sticks.

There were 10 siblings, Chin said, and much of their childhood was spent shuttling in and out of shelters their mother dug, since their village was close to an airfield that housed a battery of SAM missiles and was a prime target for U.S. bombing raids. She had only hazy memories of her brothers but recalled that De had beautiful handwriting, and that Chuong was known for his kindness and generosity.

News of De’s death came first, from a comrade in his unit in Quang Tri, saying he had died on a bright moonlit night, though official notification didn’t arrive until a year later. But even knowing where he’d died, the family had to scour the dozens of war cemeteries in the province, and it wasn’t until 2011 that they finally located the grave. The government chipped in the equivalent of about $80 to cover the costs of bringing the body home. Now it lay among the 200 or so graves in the Thach That district martyrs’ cemetery, and we went there so that Chin could burn incense, kneeling by the marble headstone that bears his name.

The search for Chuong took much longer, and it fell mainly to Chin’s niece, Tra. She took on the task at the urging of her grandmother, who insisted that she refused to die until both her boys had come home. Somehow, Tra said, the old lady had heard of this mysterious new thing called mitochondrial DNA. “I only have two teeth left,” she said, “and I have to keep them so they can identify my son.”

Tra wrote to a military-sponsored TV show that aims to help families track down their missing and is now approaching its five hundredth episode. After 10 years without a response, she wrote again and was contacted by a veteran living in Germany, and the clues he offered took her on a long odyssey through the cemeteries of the far south, until at last she found Chuong in a coastal province near Saigon. Her grandmother’s last tooth proved to be a match. She died in her nineties, content in the knowledge that both her sons had returned home.

There are graveyards everywhere in Quang Tri. It’s home to the monumental Truong Son Martyrs Cemetery, which pays tribute to the estimated 33,000 fighters who died on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and each district and commune has its own martyrs’ cemetery, 72 in all. Row after row of the headstones say Chua Biet Ten.

A woman in her fifties, Le Thi Vinh, took me to the grave of her father, Le Xan, in Cam Thuy commune, just below the old DMZ. His younger brother had been drafted into the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, or ARVN, but Xan insisted on taking his place. He was already married and had children, he argued, so if he died, there would be someone to burn incense at the grave. So he enlisted, and became a double agent, “eating government rice,” said Vinh’s brother, Le Trinh, “but worshipping Communist spirits.”

The family’s village was in a free-fire zone, and in 1968 it was wiped off the map. They were herded into a squalid resettlement camp in a nearby town, where they spent two years before moving back home to rebuild. But the 1972 offensive turned them into refugees again. Their mother hoisted her shoulder pole, stuffing rice and clothing into one basket and the four-year-old Vinh into the other, while her brother walked alongside, and they fled south. Along the way, they learned that their father had been captured and taken to the island prison of Phu Quoc, which was notorious for the variety of its torture techniques. He did not survive.

It took more than 40 years to bring home Le Xan’s remains, and the details of the siblings’ search were the stuff of an epic novel. But eventually, in 2017, they laid him to rest in Cam Thuy.

For all the pain they endured along the way, it was a story that at least brought closure, unlike so many others. Who was in all those countless rows of unmarked graves in Quang Tri? The province had been one enormous killing field, and there was nothing neat and tidy about the aftermath of a B-52 strike. Intermingled body parts were often shoveled indiscriminately into mass graves and hastily covered with lime. Thousands of southern soldiers had died in the same battles. Might they, too, be among that jumble of anonymous remains?

The Wartime Accounting Initiative will not answer that question. Honoring those who fought for the South is not something the government is ready to consider yet. The PAVN and Vietcong dead are liet sy, martyrs; the ARVN dead are still sometimes referred to with the wartime insult nguy (puppets). Reconsidering those terms would reopen too many old wounds, threatening the official narrative of the war. “Let things happen softly, with time, without big speeches,” Madame Ninh said during our conversation in Hanoi. She cited the example of the big ARVN war cemetery at Bien Hoa, which for decades was neglected, overgrown, its gates padlocked. Now, she said, after gentle urging from Ambassador Osius, it had been cleaned up, and families were free to visit and honor their loved ones, as long as no distinction was made between soldiers and civilians. As people often say, the Vietnamese have found it easier to reconcile with the Americans than with their own compatriots. And after all, one U.S. military officer with long experience in Southeast Asia reminded me, Americans have still not come fully to terms with the aftermath of their own Civil War.

Patrick Leahy is well aware that not all of the legacies of the war in Vietnam will be resolved in his lifetime. But he and Rieser, motivated by simple decency and a shrewd understanding of what Leahy calls the “quiet, behind-the-scenes beauty” of the appropriations process, have brought us a long way.

Finally helping the Vietnamese to recover their war dead seems to give both of them particular satisfaction. “It won’t involve nearly the amount of funding Bien Hoa did,” Leahy said. “But it may be the most important of all the war legacy initiatives, since there is not a family in Vietnam that didn’t lose loved ones, or know others who did.”

But in an age of corrosive partisanship, can his successors continue what he and Rieser have begun? I knew they had failed to enlist a single Republican for the delegation that had just been canceled, although perhaps the imminent midterms were a complicating factor. When I asked Leahy about the future, he answered by talking about the past and his memories, perhaps rose-tinted, of the Senate as it once was. His first congressional delegation was in 1975, he recalled, just two months after the fall of Saigon. There were dovish liberals and archconservatives on that trip to Moscow, but somehow they all got along. “You bring together people with different views, and they find they share common ground,” he said. After all, if you could find it with the Vietnamese, whose political system was so different from our own and offended so many of his convictions about civil liberties, could you really not find it with Republicans?

So did that mean he was optimistic about the future?

“Well, I’m hopeful,” he said, then paused. “Which I guess is a little step short of confident.”