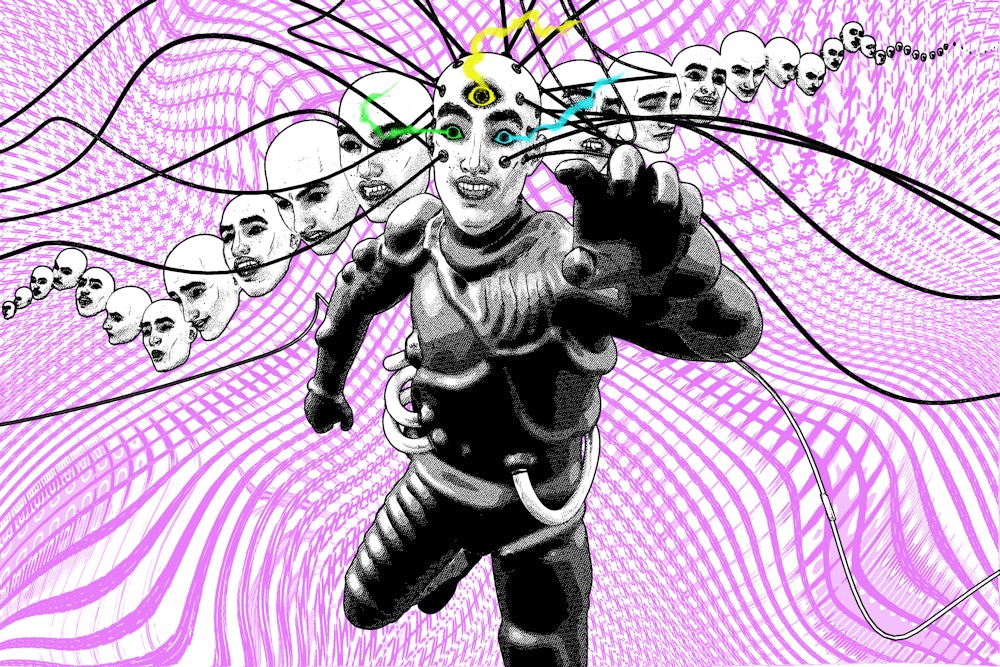

Kevin Thorbahn found himself in a hotel lobby without quite remembering how he got there. There were flashes of brilliant light, indescribable geometric patterns, and the feeling of being blasted through a gigantic stained glass window. And then he was standing in the lobby, as if checking in for a long-planned vacation. All he knew was that he was enamored with the woman behind the counter. Although “woman” wasn’t quite right—it was more like an outline of energy, a feminine purple hue.

Just as he was getting his bearings, ready to make contact with “her,” he was sucked away, the hotel lobby and entity zooming outward down an infinite hallway, until he was back to reality, staring at his prosaic furniture. N,N-Dimethyltryptamine, the molecule coursing through his body, more popularly known as DMT, was already losing its effect. It had peaked for around six minutes, although his journey felt like hours. The memories of the hotel and the being behind the counter were quickly fading like a dream soon after waking.

Thorbahn wanted more time. He wanted to stay and speak with the purple being and map the hallways of that psychedelic lodge.

In the near future, there may be a way.

Thorbahn is one of the first in a class of so-called “psychonauts” exploring new frontiers in hallucinogenic research, preparing to use a technology called extended-state DMT. When the drug is smoked, a trip lasts minutes—despite feeling much longer. But with a constant stream of DMT supplied to a user and blood serum levels of the molecule regulated, that trip can last hours or even days—seemingly an eternity.

The method might give Thorbahn and other psychonauts enough time to bring back detailed trip reports of their experience. An intriguing aspect of DMT experiences is a degree of similarity. The landscapes and beings can be recognizable to different users (a mechanical elf is a popular recurring visitor). And for Thorbahn, the trips seem “more real than real,” a quote heard often in DMT-experimenting circles. Advocates of extended-state programs want to know whether these experiences illuminate a new corner of the mind, even another dimension—or whether users are just getting really high.

Thorbahn, who has a background in biology and chemistry and runs an organic soil company in Colorado, was driving a highway late one night while listening to a psychedelics podcast when he first heard about the extended-state DMT program, DMTx, offered by Medicinal Mindfulness. The latter organization, founded in 2012 in Boulder, Colorado, by two psychotherapists, is a psychedelic therapy clinic and provides cannabis and ketamine-assisted sessions, claiming to have helped treat trauma, depression, and “feelings of meaninglessness.” Its website emphasizes that the clinic “fully complies with all local and Colorado State cannabis laws, and all federal regulations.” DMTx is a new offshoot, founded in 2016 with a long-term goal to “develop and implement FDA-approved clinical research” into DMT, according to its website. In the meantime, the website reads, “While we’ll continue to follow stringent safety protocols, working outside some of the cultural constraints of the FDA allows us to explore a model that is congruent with the passionate interests of the psychedelic community. Namely, to explore the important question: What in the world is really going on here?”

After learning of the project, Thorbahn soon submitted several essays to DMTx and was accepted as one of the original dozen or so psychonauts.

Much of the theory behind DMTx comes from a 2016 paper in Frontiers in Physiology by Andrew Gallimore and Rick Strassman, in which the authors laid out a method to maintain a stable brain concentration of DMT using intravenous infusion. “The phenomenological content of dream states and hallucinations in psychotic disorders have been studied extensively,” the authors wrote, “whilst the endogenous human hallucinogen DMT reliably and reproducibly generates one of the most unusual states of consciousness available, its phenomenology has only begun to be characterized.”

Strassman, a clinical research psychiatrist specializing in psychedelic research and author of DMT: The Spirit Molecule, is on the vanguard of studying that phenomenology. While the whole idea of studying extended trips may seem kooky to some, Strassman explained to me via email that there can be real scientific benefit to extended-state experiments. DMT is produced endogenously in mammals, meaning our brains make the molecule. But we have a much lower tolerance to DMT compared to other psychedelics like LSD. How or whether DMT fits into our natural physiology is an open question. Strassman wants to know if there is a DMT neurotransmitter system—like with serotonin and dopamine—and whether one’s tolerance or lack thereof plays a role in naturally occurring psychosis such as schizophrenia.

“An extended-state experience would provide a more leisurely approach to characterizing the DMT effect,” Strassman wrote. It also enables, he added, a “more stable and fulsome communication with the beings,” meaning the otherworldly persons many trippers report meeting. He doesn’t discount the scientific value of documenting those semimystical encounters.

Strassman is aware of how this kind of talk can be perceived. When he first received funding from the National Institutes of Health in 1990 to study DMT, he told me, colleagues were not so much skeptical as nonplussed: “Within the scientific community, at least the larger academic one, my initial results were either barely noticed or referred to in a bemused manner,” he said. “No one told me I was going to kill my career by studying DMT. In fact, no one knew what DMT was.”

Recent years, though, have seen an uptick in psychedelics research. Teams at Imperial College’s Centre for Psychedelic Research in the United Kingdom as well as the University Hospital of Basel in Switzerland are currently running the first studies of extended-state DMT.

But the DMTx program isn’t a research facility. Daniel McQueen, co-founder of the Center for Medicinal Mindfulness and principal organizer for the DMTx, was exploring therapeutic benefits of cannabis and other psychoactive compounds before learning about Strassman’s research. He couldn’t stop talking about it. And those that heard the idea asked him a lot of questions, to which he’s now developed a lot of speculative answers.

How long could a trip safely last? He thinks around three hours but in theory much longer. What happens if the participant needs to use the bathroom? McQueen has looked into astronaut diapers—adult diapers used on space walks. If two people were hooked up to an extended-state drip and placed in different rooms could they communicate in the DMT space? He has no idea but wants to try. The idea was contagious, he says.

His center plans to make use of a ballot measure Colorado voters passed in November legalizing psychedelic therapy at state-approved “healing centers.” Currently psilocybin and psilocin—magic mushrooms—are the only approved drugs (“natural medicine,” in Colorado legal terminology). But Proposition 122, as it was dubbed, allows for the use and sharing of ibogaine, mescaline, and DMT, and established a process for the state to opt to reclassify DMT as a “natural medicine” by 2026, enabling licensed facilitators to guide patients in its use.

McQueen is not a doctor, nor are the other two individuals listed as DMTx’s “team” on its website. Medical doctors are involved, the site asserts, alongside other “professional volunteers.” But “due to the nature of the DMTx program, we are choosing to keep who they are private for now.” The state has yet to set up regulations for who exactly can advise and dispense DMT.

A multi-hour intravenous infusion is not out of the ordinary—especially using fast-acting drugs—and could be performed safely in the presence of professionals monitoring vitals, according to Dr. Michael Champeau, president of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Pharmacokinetically, he told me when I contacted him for an outside opinion on DMTx’s plan, an infusion “makes sense” for a drug whose effect is so fleeting. But, he added, he has no idea what other risks are present for an intravenous DMT drip. And perhaps the greatest danger isn’t physical. Hallucinogens have been suspected in causing or exacerbating mental disorders like psychosis in rare instances. DMTx organizers, obviously, don’t advocate trying any of this at home.

So what are the first class of “psychonauts” doing exactly? At first, McQueen’s center had a couple in-person training sessions in Boulder. Participants used cannabis to elicit DMT-like states and practiced creating trip reports. But the pandemic moved the training online. Now at any given time there are a dozen or so trainees from a range of backgrounds, as the center works toward developing a protocol for its first DMT trial runs.

McQueen remains open to whether a psychonaut experience is just “in their head” or something else. Besides cohorts of artists and spiritual leaders, he says he wants to bring scientists from a host of fields to participate, potentially unlocking practical yet fantastical answers to the world’s woes. “The goal being that this would be like an advanced creative problem-solving tool for technological advancement,” says McQueen. He’s a fan of an aphorism dubiously attributed to Albert Einstein: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

The regulatory framework for legal and guided DMT trips might not be ready for some time in Colorado. (Oregon legalized psilocybin in 2020 and is still figuring out its execution.) So McQueen is looking at Jamaica as a location for the first extended trips due to the country’s lenient drug laws. Tucked somewhere between Caribbean tourists and their pockets of cruise ship meal tickets, his group will be suspended in the mind’s awesome expanse. There will be an anesthesiologist to administer the drug, McQueen says, an electroencephalogram expert to measure brain activity, experienced guides, and a team of willing psychonauts.

John Lawrentz is one such willing psychonaut. He works in psychedelic therapy, which he describes as “using your innate ability to heal.” He says it’s different from talk therapy in that the healing from a psychedelic method “happens inside yourself.” It’s not managed so heavily by something external—like a talk therapist—he explains. Lawrentz works with cannabis now but has experimented with DMT, and thinks there’s a lot of personal problem solving that happens during the minutes one is under its influence.

A growing body of evidence supports this assertion. Despite a near research ban on psychedelics during the drug war in the 1970s and ’80s, studies are increasingly showing that psychedelic-assisted therapy can help a host of mental ailments, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Pharmaceutical companies are aware. The global psychedelic drug market may reach over $6 billion by 2026, doubling in size. The largest share of that business will go to treating depression. Companies are developing an ayahuasca pill and DMT injection.

Big pharma cashing in on experiences many take as spiritual rubs some the wrong way. But the commodification of psychedelics isn’t new. Ayahuasca, a brew made from a mixture of plants that contain DMT and inhibitors that allow humans to make use of the molecule, has been used in South America for thousands of years in a diverse range of religious, healing, and social ceremonies. For the last decades, shamans have guided foreigners searching for enlightenment or adventure through versions of that ceremony—for a price. And there’s an underground network across the United States and Europe where guides—usually not Indigenous South Americans—serve the brew and keep watch on cross-legged participants in suburban homes and city flats, buckets at the ready. Drinking ayahuasca often leads to nausea and vomiting. The ceremony can last hours but is far less intense than a peak DMT trip, which the extended-state program wants to prolong.

Critics focus on what is surely lost when jettisoning the religious or cultural aspects of the traditional ayahuasca ceremony, or even participating as an outsider—foreign to the heritage in which the ceremony was created. Creators of DMTx take the spiritual aspect of the drug seriously. And they don’t appear to be trying to recreate those ancient rituals found in the Amazon. Instead, there’s a forward-looking religiosity to centers like the Center for Medicinal Mindfulness. If they are practicing a religion, it’s one that hasn’t yet been created. Their dogma and rites have yet to be pulled from the fractal DMT space.

During Lawrentz’s trainings with DMTx, he used cannabis to simulate a DMT trip and then wrote a trip report about what he experienced. “We not only want to go into these places … but we want to bring something back,” says Lawrentz. He says that can be difficult as you lose track of your five senses. “So when you don’t have those words … you have to come up with metaphors or analogies of your own.”

Crafting better descriptions of ineffable psychedelic experiences is a long-standing struggle. Psychologist Timothy Leary, counterculture LSD researcher and advocate, in 1966 endorsed the use of an “experiential typewriter” to better describe trips. The device had large buttons corresponding to feelings and sensations. Organizers at DMTx are also willing to find innovative ways to describe these journeys. A police sketch artist has gone through their program. And a key criterion when browsing potential pyschonauts’ applications is their ability to communicate their experiences.

Thorbahn, who’s been in DMTx’s program now for around four years since first tuning in to the idea on that fateful late-night drive, thinks there are two types of people who are attracted to powerful psychedelics. First, of course, there are those who like to party—dorm-room floor disciples. “And then there’s another type that look at it as more of an experiment,” he explains. They “want to explore and really understand these medicines at a deeper level.” He identifies with that second group. And his hopes for exploring the DMT space and what he can bring back are ambitious. “We might have to download some sort of information from these experiences … how to better ourselves and better the planet,” he says.

Lawrentz talks in similar terms about his participation in DMTx. He’s part of something new and strange and unknown. “It’s very equivalent to the astronauts going into space. We talk about it that way a lot. And it really does ring true,” he says.

In his DMT experiences, Lawrentz comes across those commonly reported entities—intelligent and otherworldly beings. “For my belief system, I really believe that these entities are parts of myself,” he says. There are usually two he encounters. It’s hard to describe for him, but it’s like feeling you’re alone in a room—and then not. “It would be as if you had a very intimate friend and without looking at them or touching them or talking or hearing, you just know that they’re there and they’re there for you in every possible way,” he says.

He’s felt an overwhelming sense of love in that DMT space—something so strong it seemed unearthly. And like others, he hasn’t wanted to come back so quickly, even if those entities and spaces only exist within his mind. He’d like to stay longer and find out what he can teach himself.