Earlier this year, the Builders

Association staged a virtual,

interactive performance piece featuring an unlikely cast of

characters: actual MTurk workers. Also known as “microworkers,” the turkers toil

in a highly unregulated system, helping to make Amazon Web Services’ online

algorithms run more smoothly and efficiently. Many of those in the online

performance shared that they earned only $30 to $40 a day completing rote tasks

and that their payment was often withheld for nebulous reasons.

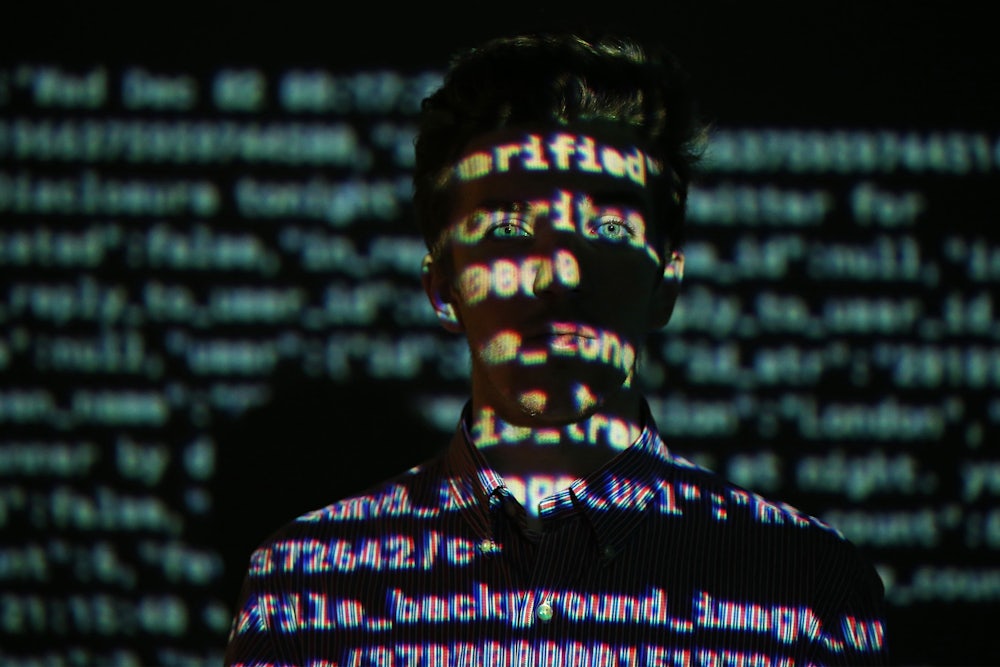

The “play”—if that is the right word for such an eerie encounter—was called I Agree to the Terms. About halfway through, the audience is invited to complete some tasks in a simulation. I downloaded a link onto my phone and watched a lo-fi tutorial. Then I began to “accept” assignments, each tagged with a level of difficulty, human intelligence task, or HIT, approval rate, and “reward” amount. I analyzed data from shopping receipts, completed market research surveys, wrote product descriptions, decoded customer messages, and answered brief questionnaires. On my computer screen, I could see the “competition”—the other audience members, who could also surveil me. A leaderboard showed where I ranked at every second. A string of unsuccessful tasks plunged me far below the 80 percent approval rating needed to stay out of the “red zone,” and I was immediately disqualified from participating in the metaverse bazaar at the end of the show (accepting only NFTs). This was just as well since I ended up making less than 20 coins.

The problems of “microwork”—not least companies’ efforts to pass it off as an innocuous “game” that grants “players” the freedom to “choose” tasks—is at the center of You’ve Been Played: How Corporations, Governments, and Schools Use Games to Control Us All. Its author, Adrian Hon, created Zombies, Run!, a smartphone game that incentivizes running and that has been downloaded more than 10 million times, and founded a company that produces games for clients like the BBC, Penguin Books, Microsoft, and the British Museum. His central argument, as suggested by the subtitle, is that “gamification has become the twenty-first century’s most advanced form of behavioral control.”

The argument isn’t entirely new. The application of game design principles like leaderboards, progress bars, points, badges, levels, challenges, and activity streaks to nongame ends has seeped into just about every domain of modern life, from sleeping and exercising to studying and social credit systems. In certain cases—like motivating users to learn a new language or pick up a new instrument—the deployment of game principles may be benign. This is what Hon calls “generic gamification.” “Coercive gamification,” by contrast, is “abusive,” “exploitative,” and “authoritarian.” This is what happens when game technology is used to get Turkers to work longer hours for lower pay. Here, games reinforce structures that penalize “users” for taking breaks, losing interest, or disobeying the neoliberal imperative to be available to work at all times.

Mechanical Turk is named for an eighteenth-century contraption that gave the illusion that it could play chess, when in fact the “machine” simply concealed a chess master who controlled its movements from within. Taking inspiration from this 250-year-old scam, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos launched Amazon Mechanical Turk, or AMT, in 2005 as a way for businesses to outsource tasks to humans that algorithms, for all their vaunted computational power, cannot perform well, such as identifying images. For workers, the experience of completing Captcha challenge after Captcha challenge often has the perverse effect of making them feel less human and more like “intelligent artifices,” to borrow Anna Weiner’s resonant phrase, or “a piece of software” catering to the caprices of invisible bosses.

Hon offers a more technical formulation: Working as a Turker essentially means living “below the API,” or application programming interface. As he writes, “If you live above the API, you’re playing the game, and if you live below it, you’re being played. You’re an NPC—a non-player character.” A 2016 study from Pew found that most “crowdworkers” earn less than minimum wage and that a majority of microtasks were short, repetitive, and paid less than 10 cents. As with other forms of gig work that use digital apps, turking further entrenches a class of alienated, precarious workers.

While “clickwork” is relatively new, the principle behind microwork—dividing tasks into smaller and smaller components—stretches a long way back. Beginning in the 1880s, Frederick Winslow Taylor, the “godfather of scientific management,” conducted a series of experiments at a steel company, measuring the outputs of factory workers and calculating their “maximum theoretical output.” As Harry Braverman wrote in Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century, Taylor split the “conception” and “execution” of work into “separate spheres.” “The study of work processes must be reserved to management and kept from the workers, to whom its results are communicated only in the form of simplified job tasks governed by simplified instructions which it is thenceforth their duty to follow unthinkingly and without comprehension of the underlying technical reasoning,” Braverman wrote. Instead of enhancing a worker’s technical ability or imparting to him greater scientific knowledge, the purpose of his work was opaque by design and intended to “cheapen the worker by decreasing his training and enlarging his output.”

This “dissociation” of labor processes from workers became a hallmark of Taylorism, whose tenets eventually spread beyond industrial labor and were absorbed by managers eager to control and rationalize the production process of various forms of work. Whereas employers in the past timed their workers with stopwatches, they now have recourse to more sophisticated technology that collects thousands of data points on their workers. The end goal, though, as Hon notes, “remains the same, which is to juice labor productivity and increase profits by reducing labor costs.”

Hon identifies any kind of work consisting of “repetitive tasks and of sufficient scale” as “a prime target for Digital Taylorism.” Taylorism 2.0 comprises everything from warehouse work to programming to truck and taxi driving. In trucking, fleet telematics systems use leaderboards and competitions to “motivate individual drivers and teams to compete for better scores, badges, prizes, and bonuses,” in the words of the founder of Cambridge Mobile Telematics. Uber uses “quests” to lure drivers into working for longer hours, and Lyft similarly offers “streak bonuses” to drivers who accept back-to-back rides. What these examples share is the reliance on large pools of data about workers—a phenomenon that has led privacy scholars to warn of a “scored society” or the rise of “informational capitalism.” The work that, for Hon, best expresses Digital Taylorism’s “infantilizing gamification,” though, is working at a call center. Here, timers on computers have replaced stopwatches, measuring the duration of calls down to the second and tracking how workers’ performance ranks next to their own past performance, their team average, and “company benchmarks.”

He cites a 2020 ProPublica investigation on Arise Virtual Solutions, a secretive company that works with independent contractors to service clients like Airbnb, Barnes & Noble, Comcast, Disney, Peloton, and Walgreens. Among other things, ProPublica found that Arise asked quality assurance performance facilitators to score agents’ calls to the sixth decimal point against a 40-item scorecard. If an agent expressed “genuine interest in helping,” he was awarded 3.75 points. If he was solicitous and used “empathetic statements,” he received two points. If he was “confrontational,” he was docked 100 points. Call center workers are an exemplary case of how companies now routinely accumulate thousands of data points on individual workers, making them less “individuals” than what Gilles Deleuze called “dividuals,” beings who are increasingly dividable and combinable, like pieces of a Lego set.

While Hon warns of the dangers of gamification, his book is not entirely a tech apostate’s account. For all his caution, he believes in ethical gaming. The gamification of civic engagement, he proposes, could help citizens better understand planning decisions and take part in democratic processes like participatory budgeting. (Other examples that he cites, like the Covid Tracking Project—a volunteer effort to collect data on Covid-19 during the height of the pandemic—seem less like instances of good gamification than marvels of crowdsourcing.) Elsewhere, Hon has argued that we should build “digital democracy systems” that foster “multiplayer” engagement, like user-friendly platforms that replicate the experience of participating in citizen assemblies.

Good gamification, for Hon, ultimately moves “beyond good design to sustainability and equity.” It would, at a minimum, require companies not to exploit game developers and people to treat each other not as NPCs but as Kantian ends-in-themselves. Systems should be designed to foster multiplayer engagement. In his own company, Zombies, Run!, for instance, Hon tells us that he prefers not to resort to methods of intrusive monitoring, doesn’t ask customers to “rate their experiences with our support team,” and doesn’t use “gamified recruitment platforms.” “There’s no set of rules that will guarantee a game’s success, but what’s crucial is that you treat everyone involved in its production and use with respect.”

Still, if gaming has a “utopian” horizon, Hon is skeptical of what it promises. As he acknowledges, games are mostly a force for stasis, a product of their “funders’ politics and of their reluctance to challenge our existing economic and political systems.” This leaves us at an impasse, or what Hon calls a “softlock,” a situation in video games where “no forward progress is possible.”

All but the most privileged are trapped in circuits of repetitive work. If their tasks resemble a game, it’s only in the most superficial of senses: We momentarily let go of our identities as sovereign, bounded subjects and assume an alternate role. But unlike in games, we don’t always accede to the terms and there’s no logging off.