“Democrats have really given Middle America the middle finger,” said Senator Jodi Ernst, an Iowa Republican, on Fox News Sunday. I would amend that slightly. I’d say that Democrats have given Iowa, and especially Iowa’s ridiculously complicated caucuses, the middle finger, and that the Democratic Party’s decision to end the Hawkeye State’s first-in-the-nation status in the Democratic presidential primary season was overdue by several decades.

Most obviously, the state of Iowa is not remotely representative of the broader population. It is 90.1 percent white, 4.3 percent Black, and 6.7 percent Latino. (The numbers add up to more than 100 because some people self-identify as both white and Latino.) Iowa is the fifth-least-diverse state, according to the Census Bureau’s diversity index, which measures the likelihood that any randomly chosen two people will be from different racial or ethnic groups. If we define “Middle America” as the area lying between the East and West coasts, Iowa is less diverse than any other state in what snobs call “flyover country,” excepting West Virginia. The other three states less diverse than Iowa are Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire, all locales where people who say “flyover” are at risk of owning vacation homes. (As part of the Democrats’ primary season revisions, New Hampshire will also be demoted, losing its first-in-the-nation-primary status to more diverse South Carolina.)

Iowa’s population also comes up short in another way: quantity. With 3,190,369 inhabitants, Iowa resides in the bottom half of all 50 states. According to the number crunchers at FiveThirtyEight, Iowa is the eleventh-most-rural state in the country. There’s a patriotic tendency, especially among conservatives, to characterize rural America as more “American” than urban America, in nostalgic tribute to our agrarian origins. But today’s concentration of the U.S. population in cities and suburbs creates disparities in state power, on a per person basis, undreamed of by the Founders. It also mocks the principle of equal political representation as articulated in Baker v. Carr, the landmark 1962 Supreme Court decision that for the first time required state legislatures and the U.S. House of Representatives to create electoral districts of equal population. The high court could impose “one person, one vote” on these bodies but not on the U.S. Senate or the Electoral College because the rotten boroughs in those institutions were written into the Constitution. Iowa already enjoys more representation, relative to its population, than it deserves in our country’s national legislature and in how we elect presidents. To pile on top of that the advantage in the nomination process that it enjoyed for a half-century was intolerable.

Another reason to flip Iowa the bird is the Hawkeye State’s dwindling commitment to the Democratic Party. Iowa hasn’t been competitive for Democratic presidential candidates during the past 10 years. President Barack Obama was the last Democrat to take the state in a presidential election, winning 53.9 percent of the state in 2008 and 52 percent in 2012. Candidate Donald Trump won 51.2 percent in 2016 and, after four years as president that ought to have dispelled any illusions about the man, Trump actually increased his vote in the state, to 53.1 percent in 2020.

Republicans now control the Iowa governorship, large majorities in both houses of the Iowa state legislature, and, starting next year, the entirety of the Iowa congressional delegation. The only Democrat who will still hold statewide office in Iowa next year will be state auditor Rob Sand, who squeaked by in the midterms with 50.08 percent. After the November elections, Democrat J.D. Scholten, who ran unsuccessfully against Representative Steve King in 2018, called it “just another year of getting punched in the face.” If the Democratic Party is now giving Iowa the middle finger, it’s doing so only after Iowa gave Democrats the middle finger.

Also: How do you justify allowing a state to keep a privileged spot on the primary calendar after its governor, Kimberly Reynolds, signs into law a bill, passed by the state legislature with not a single Democratic vote, that reduces access to the ballot? The bill shrank the number of early voting days from 29 days to 20, closed polling places at 8 p.m. rather than 9 p.m., and disallowed any ballot received after 8 p.m. on Election Day (previously the law counted any ballot posted before Election Day). Reynolds isn’t an active 2020 election denier, but she campaigned for Trump in 2020, refused to blame Trump for the violence on January 6, and said, “When you have half of the electorate that feels that maybe something is not valid, then that’s a concern for our republic and we want to do everything we can to address that.” Why should Democrats reward such a weak commitment to democratic governance with an early spot on the nomination calendar?

Also: This may be unfair, but Iowa underperforms in the culinary department, and that matters to the many political candidates and reporters who must visit the place on a quadrennial basis. As I observed 23 years ago in Slate, Iowa’s signature dish, “broasted” chicken, is … well … not good (and chicken is really, really hard to screw up). The great regional food maven Calvin Trillin told me in 1999 that Iowa excels in another, less publicized dish, the pork tenderloin sandwich. But I’ve since learned that delicacy was actually invented in Indiana.

You ask, “What about corn?” Yes, Iowa produces more corn than any other state. But most of this corn becomes ethanol, a highly dubious gasoline additive. Writing three years ago in Politico, Michael Grunwald reported that two out of every three corn stalks grown in Iowa get sold to ethanol producers.

Starting in the 1970s, ethanol was blended into gasoline to reduce dependency on foreign oil. Later it was used to replace lead as an “octane enhancer,” and later still it was used to reduce air pollution. But eventually environmental scientists observed that ethanol actually contributed to air pollution by increasing gasoline’s Reid vapor pressure, which caused the gasoline to evaporate more rapidly at the pump and create more ground level ozone than if the gasoline contained no ethanol at all. Also, climate scientists figured out that growing all that corn released an amount of carbon into the atmosphere equivalent, over a period of five years, to 20 million cars. Whoops!

Even so, laws and government regulations continued to encourage ethanol production. Eventually ethanol became (and remains to this day) “the most-consumed non-petroleum fuel in the United States,” according to a report issued last year by U.S. Energy Department. Why did this happen? Because of the Iowa caucuses.

For decades, Democratic presidential candidates have threatened to get rid of subsidies and other forms of favorable government treatment for ethanol, only to cave as they realized that kind of talk is political suicide in first-in-the-nation Iowa. Bill Bradley ran for president in 2000 determined to challenge the ethanol lobby; he folded. Hillary Clinton did the same in 2016. So did Corey Booker, Kirsten Gillibrand, Elizabeth Warren, and even the supposedly fearless Bernie Sanders. On the Republican side, Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, and Ted Cruz did the same. You can oppose this planet-warming subsidy to agribusiness or you can run for president, but you can’t, apparently, do both. Maybe demoting Iowa in the primaries will help Democrats change this cynical equation. (Republicans are leaving the Iowa caucuses where they are.)

A final reason to flip Iowa the bird is the Iowa caucuses themselves. For pointless complexity and unrepresentativeness, the Iowa caucuses give the Electoral College a serious run for its money.

A primary is nice and simple: Voters are presented with a list of potential nominees, and they choose one. Even when this is complicated by ranked choice voting and/or a runoff, it never gets very complicated. It’s just a matter of who you like best, and in what order.

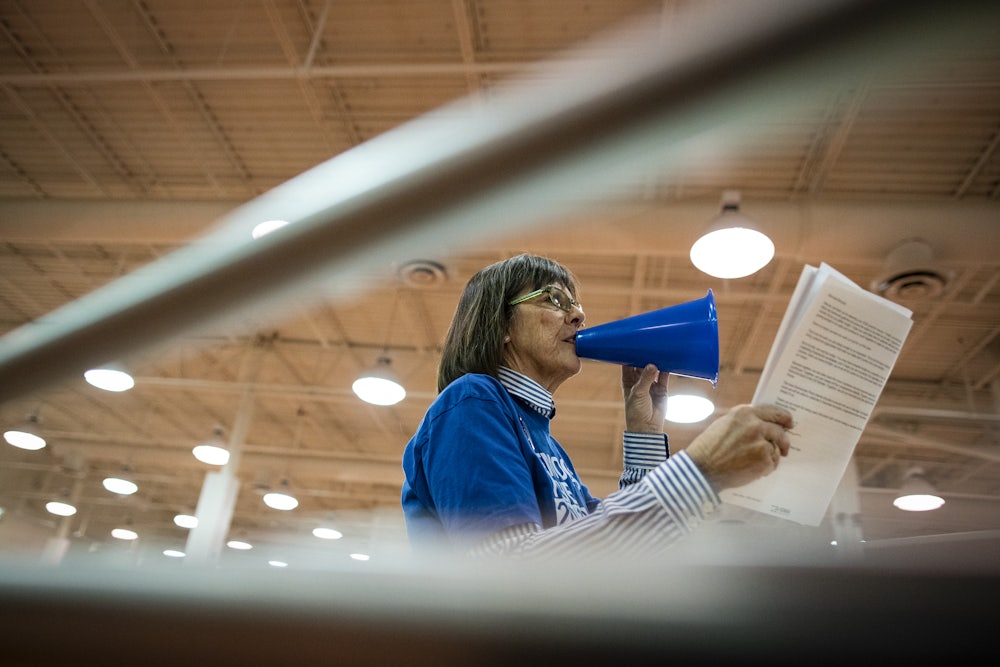

The Iowa caucuses are different. They’re so complicated that even The Des Moines Register has to simplify a little bit to explain how they work to Iowa readers. The complete process is described here. You go to your precinct caucus, debate the merits of your candidate with other attendees, listen to the other attendees do the same for their candidate, then join a cluster that supports whichever candidate you decide to support. If your cluster is big enough that it represents 15 percent of all attendees, you sign a presidential preference card and go home. If your group isn’t big enough, you have to persuade others in the room to join your cluster, join somebody else’s cluster, or join an uncommitted cluster. In 2020, caucusgoers were also permitted to cluster remotely in 99 “satellite locations” in Iowa, in other states, and, in three instances, in other countries. Caucus results are based on the proportion of caucusgoers who cluster for each candidate in each precinct or satellite location.

Are we done? As far as the press is concerned, yes. The caucuses take an hour, and after that results from all precincts are made available. In 2020, though, Iowa Democrats screwed it up—something to do with an iPhone app—and there were recounts in several precincts, delaying confirmed results by six days. This did not endear the Iowa caucuses to the national party.

So we’re done, right? Not the caucusgoers. Based on the number of people who sign preference cards for each candidate at the precinct level, representatives are sent to county caucuses. At the county caucuses, the process followed at the precinct caucuses is repeated. Then representatives are sent to statewide caucuses, where the process is followed a third time. It’s a freaking nightmare, not to mention a time commitment no normal person is able to accommodate.

Turnout is typically much lower for the Iowa caucuses than it is for primaries. Big-D and small-d democrats are supposed to care a lot about maximizing voter participation, but that’s something the Iowa caucuses can’t deliver. If the Democrats hadn’t invented them in 1972, when the party took a notably left turn with the nomination of George McGovern, one would be tempted to call the Iowa caucuses a conservative conspiracy to minimize the role minorities and lower-income people play in the nomination process. In truth, the Iowa caucuses are something else—something encountered, sadly, quite often in Democratic politics. They are an inadvertent and self-defeating strategy to minimize the role minorities and lower-income people play in the nomination process.

If Republicans had last week dreamed up the Iowa caucuses, the Brennan Center would be holding press conferences to flag this outrageous new form of vote suppression. Instead, Democrats are finally giving the Iowa caucuses the comeuppance they deserve. The only matter to grieve over is that it took so long to happen.