It’s been nearly six months since the Supreme Court handed down its blockbuster ruling in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen. The 6–3 ruling, which fell along the court’s usual ideological divide, introduced a sweeping new history-and-tradition test for lower courts to use when scrutinizing restrictions on Americans’ ability to own and carry firearms. This has resulted in a series of lower court decisions that could radically reshape where and how guns fit into everyday American life.

Until recently, most federal courts had settled on a two-step test for the constitutionality of gun restrictions. The first step generally required judges to decide whether the restriction fit within a history or tradition of gun restrictions. In short, if a court found examples of similar restrictions when the Second Amendment was ratified, then it would be presumptively constitutional. If no examples could be found, the courts would then move to the second step and try to balance the need for the restriction against the individual right to bear arms. That balancing act often allowed restrictions to stand.

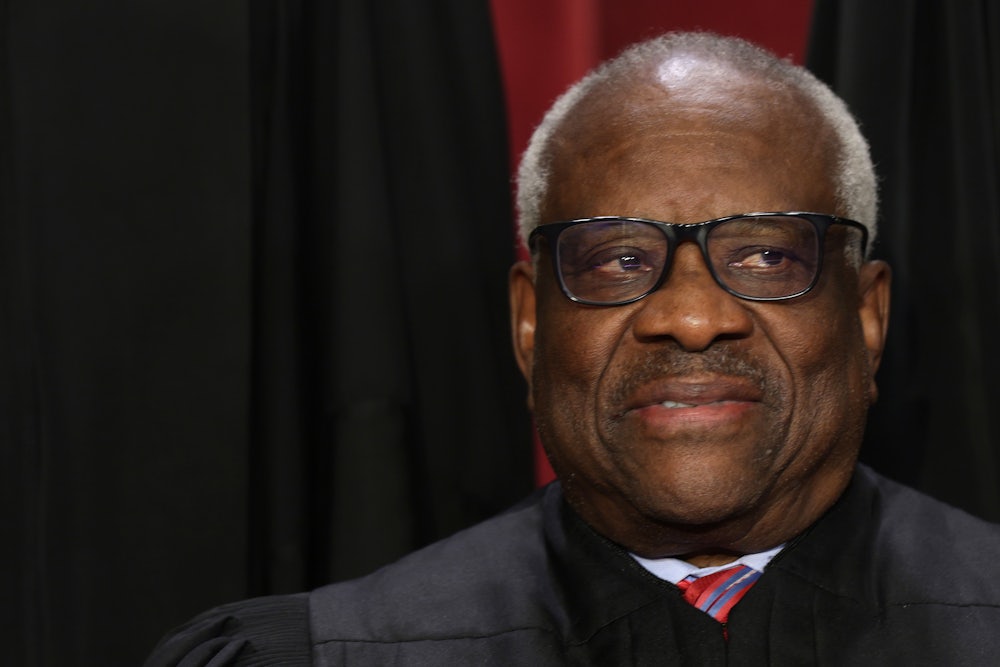

Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the six-justice majority in Bruen, eliminated the second step altogether. “When the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct,” he wrote for the court. “The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only then may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s ‘unqualified command.’” In short, it made originalism mandatory in Second Amendment cases.

Applying the history-and-tradition test to existing gun laws has already led to some extraordinary conclusions. Earlier this month, for example, a federal district court judge in Texas struck down part of a law that sought to keep guns away from people accused of or at risk of committing domestic violence. The defendant, Litsson Antonio Perez-Gallan, was a truck driver who was traveling along the U.S. border with Mexico when he was stopped and searched by border patrol agents. Those agents found a handgun in his possession and later learned that a Kentucky family court had issued a restraining order against him. Federal prosecutors charged him with violating a federal law that forbade possession of a firearm while under certain court orders.

Perez-Gallan moved to dismiss the charges after the Bruen ruling, claiming that the statute infringed on his Second Amendment rights. Judge David Counts, who serves as a federal district court judge in Texas, ultimately sided with him. In a ruling earlier this month, he grounded his conclusions in the history-and-tradition test laid out in Bruen. “This straightforward historical analysis, however, reveals a historical tradition likely unthinkable today,” Counts noted. “Domestic abusers are not new. But until the mid-1970s, government intervention—much less removing an individual’s firearms—because of domestic violence practically did not exist.”

His survey of the historical evidence started with the seventeenth-century Puritan communities in what eventually became colonial Massachusetts, which represent the oldest continuous legal tradition that is available to scrutinize. It is not exactly a model of feminist jurisprudence. “During that almost 200-year period, only 12 cases involving wife beating were prosecuted,” Counts noted. “Zero complaints during that time were for child abuse. Another study of the six New England colonies from 1630 to 1699 confirmed the same—only 57 wives and 128 husbands were tried on charges of assault.” He observed that the law of that era prioritized “maintaining the nuclear family” over “separating the abuser from the victim through a prosecution.”

Nor did things improve for women after the Revolution. “Even in the late nineteenth century, many states still adhered to the belief that without serious violence, the government should not interfere in familial affairs,” Counts explained. “In just one of many examples, the North Carolina Supreme Court stated as late as 1874 that ‘if no permanent injury has been inflicted, nor malice, cruelty nor dangerous violence shown by the husband, it is better to draw the curtain, shut out the public gaze, and leave the parties to forget and forgive.’” While he cited instances where courts and private citizens imposed harsh punishments on abusers, the judge concluded that “consistent examples” of the government seizing their guns were “glaringly absent” from the historical record.

One response to this would be to note that, historically speaking, the law and the courts did not fully regard women as persons for most of this country’s history. There are Americans alive today whose mothers, at some point in their adult lives, were barred by law from opening a bank account in their own name, serving on a jury, holding public office, or voting. Since domestic violence laws are inescapably linked to a woman’s social and legal autonomy, it follows that a society that would diminish one would also diminish the other. Applying colonial Puritan jurisprudence on this subject to a country that ratified the Fourteenth and Nineteenth Amendments is not applying historical precedent. It is imposing a foreign law.

Only the reader can decide whether Counts, who is bound by Supreme Court precedent in all circumstances, actually thinks that this is how the Second Amendment should best be interpreted. A few months earlier in September, he decided another post-Bruen Second Amendment case. This one involved a defendant who sought to overturn a provision in federal law that forbids people who are under indictment for felonies from buying or receiving a gun.

Counts ultimately sided with him after applying the history-and-tradition test and struck down the provision. He also noted some fundamental flaws in doing so. “For one thing, one could easily imagine why historical analogies from the 18th century would be difficult to find,” he wrote. “For example, if one lived more than a day’s journey from civilization, a firearm was not only vital for self-defense—it put food on the table. Indeed, whether fending off wild animals or hunting, a firearm was a necessary survival tool.”

“That is why disarming someone was likely unthinkable at the time—no firearm in the wilderness meant almost certain death,” he explained further. “So finding similar historical analogies is an uphill battle because of how much this nation has changed. Society, population density, and modern technologies are all examples of change that would make something unthinkable in 1791 a valid societal concern in 2022. But the only framework courts now have is Bruen’s two-step analysis.” It is hard not to hear a tone of skepticism and perhaps reluctance in that last sentence.

Other federal judges have wielded the history-and-tradition test in much stranger ways. After the Bruen decision, New York lawmakers rewrote the state’s concealed-carry law to replace the one overturned by the Supreme Court. A group of gun owners sued to block that law from taking effect as well, challenging the constitutionality of its various provisions under the history-and-tradition test. Judge Glenn Sudabby, a federal district court judge in New York, granted the plaintiffs a preliminary injunction to block most of the law from taking effect while litigation unfolds.

Sudabby’s 184-page decision had two major components. The first one looked at New York’s new qualifications to obtain a concealed-carry license, which replaced the more subjective and discretionary system that the state used before the Supreme Court’s ruling in June. Sudabby blocked provisions that would have required applicants to show “good moral character,” to provide the name of their spouse and any children living in their home, and to provide their social media accounts for official scrutiny. The second component involved location restrictions: prohibitions on carrying guns in schools, airports, zoos, and more. Most but not all of those provisions also failed Sudabby’s analysis.

In Bruen, the dissenting justices warned that the history-and-tradition test could lead to judges engaging in a historical analysis for which they are untrained and unsuited. “We are unpersuaded,” Thomas wrote in response, in a footnote of his majority opinion. “The job of judges is not to resolve historical questions in the abstract; it is to resolve legal questions presented in particular cases or controversies. That ‘legal inquiry is a refined subset’ of a broader ‘historical inquiry,’ and it relies on ‘various evidentiary principles and default rules’ to resolve uncertainties.” He noted, for example, that judges will be bound by whatever historical evidence is presented to them by the parties.

That distinction between abstract historical questions and concrete ones appears far more murky in practice than in theory. Thomas’s assertion that judges would not engage in their own freewheeling research also did not last long. “Although it is not the Court’s duty to find analogues for Defendants or ‘sift’ through those analogues, the Court has (given the importance of the issues presented) tried to find analogous laws to the extent the State Defendants may have not provided them,” Sudabby wrote, adding in a footnote that he conducted searches in a Duke University database of historical gun laws and then tasked the Second Circuit Court of Appeals’s librarian to obtain them. After finding the analogues, he then proceeded to sift through them.

That sifting proved to be far more subjective than it first seemed. Take his analysis of whether guns can be carried in “public playgrounds, public parks, and zoos.” New York provided almost two dozen city ordinances and state laws from across the nineteenth century that banned carrying guns in those places or similar ones. Sudabby discarded territorial laws from Arizona and Oklahoma because they were, per Bruen, “‘localized,’ ‘rarely subject to judicial scrutiny’ and ‘short lived.’” He arbitrarily threw out laws from the 1890s because they came “too late” to say anything about the contemporary understanding when the Second and Fourteenth Amendments were ratified in 1791 and 1868, respectively. Of the remaining handful, he noted that they only came from a handful of states and thus may not have “represented” a national consensus. Sudabby ultimately blocked enforcement for parks and zoos but allowed it for playgrounds.

All of these decisions may yet be overturned or curtailed by the federal appellate courts, which are only now beginning to hear Bruen-related appeals. It is also unclear whether the Supreme Court itself will embrace these historical understandings if it deigns to review them. As I noted earlier this year, there still appears to be a split among the conservative justices about just how broadly they should read the Second Amendment. In the lower courts, however, broad readings and historical oddities appear to be carrying the day.