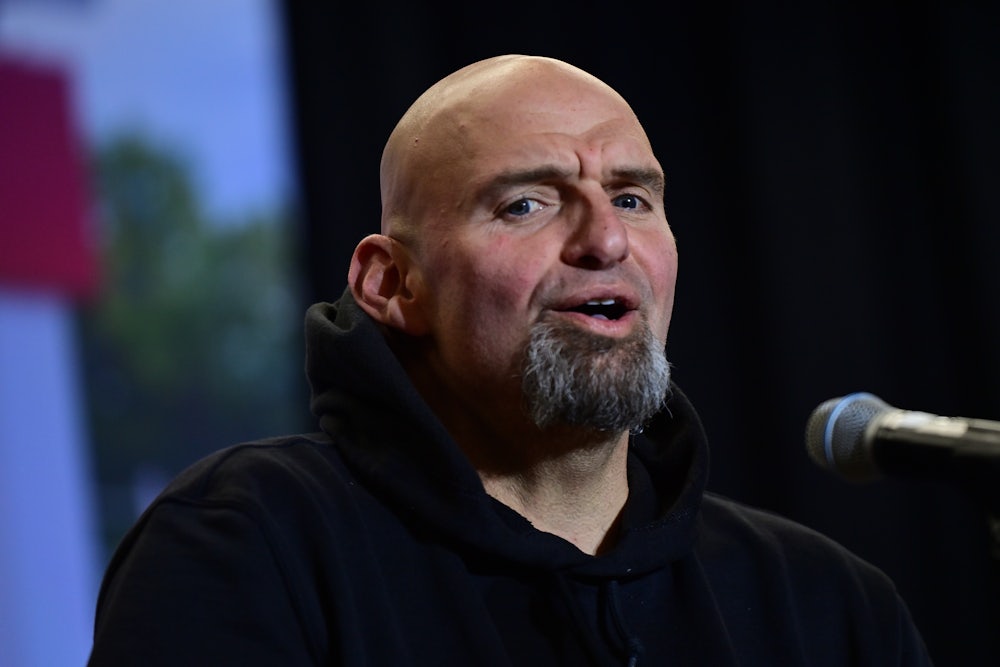

A day before Pennsylvania senatorial candidates John Fetterman and Mehmet Oz met for the first and only time to debate, Fetterman’s handlers were pretty openly trying to do what’s known as “manage expectations”—campaign-speak for “trying to set a clearable bar.” This is typical tradecraft from campaigns, though it is perhaps especially necessary when the candidate in question suffered a stroke only five months earlier. So the expectations were managed thusly: Fetterman, his campaign indicated, is not a polished debater; his opponent was a well-oiled professional who had hosted television shows. And Fetterman was still recovering: Expect “awkward pauses, missing some words, and mushing other words together” and “temporary miscommunications at times.”

And that was exactly what happened: Fetterman misspoke repeatedly, he jumbled words and got tripped up in sentences, at times descended into near incoherence. It was very uncomfortable to watch. It was also not particularly surprising to watch. That’s what recovering from a stroke looks like. Those who’ve been watching Pennsylvania’s high-stakes Senate race have likely seen Fetterman exhibit these symptoms prior to last night, albeit in more controlled and comfortable settings than a high-pressure debate. A week ago, his doctor released a statement indicating that Fetterman was speaking without “cognitive deficits”—something that was also apparent during the debate.

So much for all that. Fetterman’s performance has been greeted throughout the press as a disaster—not just a turning point in the debate but a world-historical error. Axios briefly mentioned a telling statement from Dr. Oz—he said that abortion should be a decision made by a “woman, her doctor, and local political leaders”—but spent most of its morning dispatch focusing on Fetterman’s communication issues. “Democrat John Fetterman began his first answer at last night’s high-stakes U.S. Senate debate in Pennsylvania by saying: “Hi! Good night, everybody,” the dispatch began. “It was downhill from there.” Politico’s Playbook went further, spending three tortured paragraphs making the case for why these communication issues were so important:

WILL IT MATTER?—Voters are not doctors. Many are myopic, distracted, and quick to make judgments with limited information. If there’s one thing everyone knows about campaign debates, it’s how superficial they are. We all remember RICHARD NIXON’s suspicious stubble and GEORGE H.W. BUSH’s impatient glance at his watch and AL GORE’s annoying sighs and DONALD TRUMP’s manic interruptions more than anything any of them said.

The median voter in Pennsylvania is a middle-aged white person with a mid-five-figure salary who did not attend college. That demographic is perhaps the least likely to be following the Fetterman ableism debate on Twitter and MSNBC.

A casual voter tuning in Tuesday night might have known Fetterman had suffered a stroke, but that voter would have to have been following the race pretty closely to know that his struggles with speech reflected a common “auditory processing disorder,” in his doctor’s words, and not a deeper neurological infirmity.

These are very revealing paragraphs. For starters, one thing that Politico could do, in this instance, to help resolve the confusion of casual voters as to whether Fetterman suffers from a cognitive impairment or merely a stroke-related auditory processing disorder is simply state the facts of this particular case in a plain English sentence. Instead, what you see here is Politico “reporting” on the perceptions of hypothetical people as if that were information and not speculation.

But the speculation allows the opportunity to spin a narrative yarn. The underlying assumption is that voters will see Fetterman’s struggles and automatically recoil—and assume from there that he was having cognitive problems. There is, moreover, an assumption that these same hypothetical voters would choose not to seek out more information on his condition. There’s a further assumption that voters would not be inclined to look at Fetterman’s condition with empathy or even familiarity—despite the fact that strokes affect nearly one million Americans every year. Instead, the assumption is that voters will see someone unfit for office.

It may very well be the case that voters will follow this train of thought and reach these conclusions. But we don’t yet know anything about how voters saw this debate—or even if voters were really paying attention. There won’t be polling that reflects postdebate shifts until next week at the earliest. Pundits are simply guessing. They’re also building convenient narratives: in this case, one in which, should Oz win, this debate will be identified as a turning point—either the moment Fetterman lost the race or something he will overcome on his march to victory.

But this also doesn’t make sense: The race in Pennsylvania was tightening long before Tuesday’s debate. Per FiveThirtyEight’s model, Fetterman was leading by an average of more than 10 points a month ago; that lead is now hovering around two points. It’s possible that this debate will augur a substantial shift. But it looks like the “turning point” in the race already happened, probably because of some tangible but boring reason—such as undecided conservatives simply “coming home” to support the Republican candidate.

Meanwhile, discussion of Fetterman’s condition has drowned out much of the policy that was up for debate last night. For that matter, the race’s potential to decide the makeup of the Senate for the next two years has also been occluded. Instead, a lot of energy was spent on the unknown impressions of unconsulted voters. Naturally, there was little effort made to establish the facts about Fetterman’s recovery or how he’s fared communicating in other settings. Frankly, it might have been useful to note that you can have an auditory processing disorder and still serve in the U.S. Senate.

At the same time, there are deeper biases on display. Last week, Herschel Walker similarly stumbled through a debate in Georgia—only in addition to his typical incoherence, he also revealed a deep lack of familiarity with policy and governance. Walker didn’t know, for instance, that there was a federal minimum wage. Somehow, that debate performance was seen as, at worst, a draw—if not an outright Walker win—because he cleared the staggeringly low bar he had set for himself. Walker, I suppose, could also improve. He could learn how the federal government works. He could try to understand policy or hire someone who does. Unlike Fetterman, he’s shown no indication that he actually wants to apply himself to these tasks.

Fetterman’s health is an important campaign issue; it’s proper to criticize his campaign for not being more forthcoming about his road to recovery and the obstacles he’s facing. Such an effort might have greatly benefited his candidacy last night, as it would have given voters and local media a better view into his struggles. Such an effort might have helped to counter the narrative that emerged once all the pundits who’d parachuted into the race got their first long look at it. Since there’s little reason to believe at this point that he won’t continue to improve or that his communication issues reflect serious cognitive problems, they can still take up this strategy. But this episode is worth remembering for what it reveals about the political media’s tendency to make up an imaginary voter—someone uninformed and callous—that they can deploy whenever they want to shift a narrative.