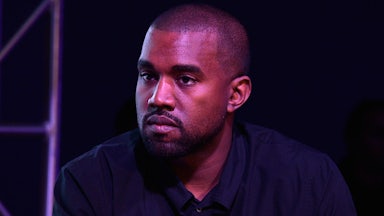

Why is Kanye West interested in buying the far-right social media platform Parler? The answer likely isn’t that different from the reason why Donald Trump started his own alternative social media network. Having been locked out of Twitter and Facebook for antisemitism—just as Trump had been banned for lying about the results of the 2020 election and fomenting a coup—Kanye just wanted a place where he knew he could always post. “In a world where conservative opinions are considered to be controversial,” he reportedly said in a statement announcing the deal, which has not closed or been confirmed by West, “we have to make sure we have the right to freely express ourselves.”

Sure, why not? We have, after all, heard this before, both from Trump and the man who seems like he may finally actually maybe be on the verge of buying Twitter: world’s richest man Elon Musk. This is their core belief: The big social media platforms have inherent liberal biases; the principles of free speech and expression demand new platforms. Naturally, there’s an alternative supposition here, which is that catering more to conservatives (Musk’s plan for Twitter) or entirely to the far right (the approach more or less taken by Trump’s Truth Social, Parler, and other platforms like Gettr or Gab) is also just a good business decision.

The idea that catering to the base awoken by Donald Trump in 2016 is a certain moneymaker is a familiar one. These voters were, after all, weaned on more traditional conservative media. Fox News’s late-night programming, the Drudge Report, the late Rush Limbaugh: These weren’t merely part of a media diet—for conservatives, this was a totalizing culture. But the Trump-pilled base adds a twist: Its deep mistrust of the conservative establishment that Trump was running against nearly matched its disgust at the so-called liberal media. And so there’s been a simple plan: Build new structures for this audience, and milk the resulting cash cow.

Except it hasn’t really worked out. These platforms are relative ghost towns compared to the forebears they’re attempting to imitate. Truth Social, and the special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, deal to which it is attached, has already been subjected to numerous fraud inquiries and is already struggling financially. Parler is being jettisoned by its primary backer, the wealthy Rebekah Mercer, who has subsidized, among other right-wing projects, Breitbart News and Cambridge Analytica. These alternatives to Twitter are failing at their primary aims of making money and of influencing politics. If the sale of Parler goes through to West, it won’t herald a revival, it will engrave an epitaph.

One of the recurring themes of Donald Trump’s political career is the idea that he has sacrificed a great deal by running for and serving as president. “I lost massive amounts of money doing this job,” the then president told The New York Times in 2019, during an interview in which he called the job “one of the great losers of all time,” financially speaking. Later that year, he estimated that he had lost $2 billion to $5 billion that he could have made had he continued to run his businesses instead of entering politics. Perhaps Trump’s biggest failure as a businessman was not recognizing that becoming the most highly scrutinized public figure on the planet might diminish his ability to keep making money through shady dealings and literal tax fraud.

Naturally, even these complaints held little merit: Trump, in typical fashion, was vastly inflating his potential earnings—he was hardly making that kind of money in his pre-politics years, with much of his income coming from licensing deals and TV hosting. But some of his frustration was very real: He believed that becoming president would be a new profit center for the Trump Organization, with legions of supporters filling his coffers. While the Trump presidency was a massive stress test for government ethics, Trump wasn’t really able to turn his White House tenure into a cash cow, though he certainly tried, particularly via his since-sold Washington, D.C., hotel.

It’s not like Trump only recently came to believe that public service would propel him to new plutocratic heights. Speaking to Fortune magazine in 2000, Donald Trump made a prediction that would be repeated again and again during his presidential run 16 years later. Boasting about his campaign stops during an aborted run for the Reform Party nomination that year, Trump told the magazine, “It’s very possible that I could be the first presidential candidate to run and make money on it.” As president, Trump reportedly frequently grew frustrated at being unable to make money from his supporters due to America’s campaign finance laws.

So it’s no surprise that his major postpresidential activity—besides stashing boxes full of government secrets into Mar-A-Lago hidey-holes—was a hastily arranged SPAC deal. The scheme hung on a start-from-scratch multimedia conglomerate, in which Twitter-clone Truth Social would be the hub from which many as-yet unlaunched media entities, including an entertainment division and news network, would branch off. (That entity, the Trump Media & Technology Group, has been trailed by accusations of fraud more or less since its inception and is the subject of numerous investigations.)

Trump’s biggest problem is that he was late to the party: The space for these right-wing, “free speech”–oriented Twitter clones was crowded long before anyone scratched out what Truth Social was supposed to be on the back of a cocktail napkin. There’s no real difference between any of the products. Truth Social’s main selling point—perhaps its only selling point—was Trump’s affiliation. But those who think Twitter is biased against conservatives (or who have been banned from posting on it) have a bunch of different options. When the potential user pool is simply right-wingers with poster-brain who can’t or won’t use Twitter, it’s hard to see much of a business being built on their backs. When this niche user base gets divided between several different upstart platforms, the profit potential drops substantially.

Beyond that, if you’re a conservative, there’s still a strong incentive to simply be on Twitter. While the firm may be small compared to other social media giants like Meta, it still has a much larger pool of potential users than any of these right-wing alternatives that pitch themselves to outcasts. If you are conservative and don’t post hate speech or blatant lies about the 2020 election—or are willing to do so in ways that don’t get noticed so that no one cares—you can just be on Twitter. Which is apparently where the fun is: “For Trump and his online base, Twitter, where virtually every member of the elite MAGA enemies list has a blue check, offered a unique product: direct lib-triggering at scale,” writes John Herrman in New York magazine. “For free! An incredible deal and probably a fatal indictment of the entire platform but, nevertheless, we post on.”

That’s the other problem with these Twitter alternatives: The trolls can’t compel the trolled to sign up. And so it turns out that the world without the blue checks and liberals is just monotony. There’s no way to chase the highs of that period when it seemed that Trump’s tweets controlled the very fabric of reality itself. That era, of course, ended long before Trump was banned from the platform and is unlikely to return, even if he were elected president. But it can’t be revived on a platform where Trump’s enemies all have the option of opting out.

Platforms like Parler or Truth Social were supposed to be havens for conservatives who didn’t have a home in “liberal” spaces like Twitter or Instagram. But there are places for people with these views everywhere; even on social media platforms, where claims of anti-conservative bias are routinely shown to be baseless. Institutions like Fox News, moreover, have regained their footing at the center of the right-wing ecosystem, lessening the need for start-up competition from firms like Truth Social.

The category error at the center of all of these Twitter alternatives is that right-wing shitposters don’t actually need or want a safe space to play together. They want to be a part of a battlefield. This isn’t a thing that a right-wing version of Twitter can provide, so there just isn’t a point for any of these sites to exist. It’s no wonder Rebekah Mercer wants to cut bait, especially if Kanye West is willing to pay big bucks just so he can have a place to post again. But he may find that one man having all that Parler isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.