If you tried to invent a fictional scandal to make the case for abolishing single-member districts, you would be hard pressed to outdo the real scandal that is now consuming Los Angeles and its political elite. The Los Angeles Times published an audio recording earlier this week of three prominent City Council members and an influential local labor leader that was recorded last year. In it, they discuss the then-ongoing redistricting process—and how to warp it to their advantage.

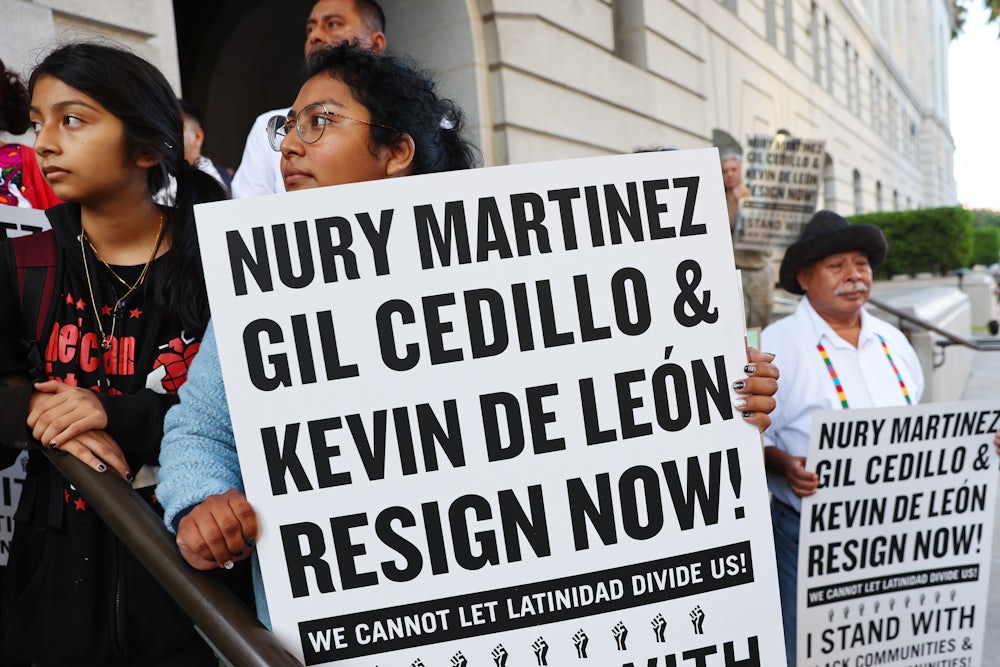

Most observers have understandably focused so far on the language used by the City Council members on the tape. One of them, former City Council President Nury Martinez, described fellow City Council member Mike Bonin, who is white and gay, as a “little bitch” and his adopted Black son as “parece changuito,” meaning “like a monkey.” (She has since resigned.) Other participants in the conversation describe ways to divvy up certain neighborhoods based on the ethnic communities that live in them. In Los Angeles, which was an epicenter of the nation’s racial strife in the 1990s, these comments carry an even heavier weight.

What has received slightly less attention is the exact context for the remarks. The tape was apparently made last year during the City Council’s redistricting process. Los Angeles elects 15 members to its City Council from single-member districts, just like the U.S. House or any of the 50 state legislatures. After the 2020 census, the City Council redrew its electoral districts to reflect population changes and comply with the one person, one vote rule. Though the city has an independent committee to assist during the process, it is the members themselves who have the final say.

The tape makes clear that City Council members had more on their minds than simply adjusting boundaries for population changes. When discussing the addition of certain streets to a district of Koreatown, Martinez questioned whether their inhabitants should be counted as part of the now largely Hispanic neighborhood. “I see a lot of little short dark people,” Martinez said, apparently in reference to Oaxacan immigrants from Mexico. “I was like, I don’t know where these people are from, I don’t know what village they came [from], how they got here.” According to the Times, she then added, “Tan feos,” which translates to, “They’re ugly.”

There are also indications that the council members sought to gerrymander the City Council for the benefit of certain interest groups and the detriment of others. “It serves us to not give [Raman] all of K-Town,” Martinez said in the recording, referring to the Koreatown neighborhood and a fellow City Council incumbent. “Because if you do, that solidifies her renters’ district and that is not a good thing for any of us. You have to keep her on the fence.”

And the members apparently sought to ensure that certain economic assets would end up in districts controlled by them and their allies. Martinez’s “little bitch” comment toward Bonin, for example, came in the context of potentially stripping his district of the Los Angeles International Airport. Stadiums, universities, and other public and semipublic assets also came up for discussion as part of what the Times described as asset gerrymandering: the distribution of economically productive institutions within legislative maps.

At first glance, this might not make much sense. Voters don’t live in stadiums or airports, so there are no votes to reallocate along the way. That may be why asset gerrymandering isn’t a major factor in federal redistricting fights. But it is unusually salient in a city like Los Angeles, since those assets can come with ties and access to wealthy donors and even sources of political patronage. City Council members “want big-pocketed people in [their] district,” one activist told the Times for an article discussing the phenomenon earlier this week.

The tape also underscored that gerrymandering is not the product of any specific political party. The GOP’s efforts on that front have received the most attention in recent years, and justifiably so: Republicans tend to be more aggressive gerrymanderers and less interested in reforms. GOP-led states also tend to have fewer redistricting reforms in place. The conservative legal movement itself tends to be more hostile to efforts to rein it in as well, and the Supreme Court’s conservative majority has dealt reformers a series of major defeats in recent years.

Democrats, however, are just as susceptible to gerrymandering’s siren call. One of the Supreme Court cases where the justices barred federal courts from hearing partisan-gerrymandering claims, for example, involved a marginal congressional district in Maryland that state Democratic leaders had tried to flip to their column by diluting Republican voters’ strength. Gerrymandering questions have also dogged Democrats in states like Illinois and New Jersey in recent years.

What makes the L.A. scandal all the more notable is that partisan concerns weren’t even an issue here. The City Council has 15 seats and 15 Democrats filling them. It is unlikely that a Republican or third-party candidate will win a seat anytime soon, for reasons that have nothing to do with legislative maps. But a certain amount of factional strife is inevitable in any political group, and the necessity of redrawing single-member districts will produce perverse incentives for those in power to maintain it.

A natural response to this scandal might be to expand the state’s redistricting reforms to the City Council level. Under California law, redistricting for House races and the state legislature is handled by an independent nonpartisan commission. For one, depending on how Moore v. Harper—the upcoming case involving what’s known as “independent state legislature theory”—is decided at the Supreme Court this term, the court’s conservative justices could ultimately revisit a 2015 ruling that narrowly upheld those commissions as constitutional. Even if the justices don’t go that far, leaving the single-member district system intact wouldn’t necessarily produce more open or competitive races.

Angelenos could instead consider replacing the single-member district system with one that runs on proportional representation. As its name suggests, this means that each electoral group or party receives a number of seats that is proportional to its share of the vote. This system has multiple benefits, as I’ve noted before, including ensuring that every citizen’s vote is actually reflected in the final makeup of a legislative body.

In an interesting coincidence, a group of prominent political scientists wrote a letter this week urging Congress to abandon the current electoral system for House races after the midterm elections this fall. They noted that the current winner-take-all scheme—an inevitable feature of single-member legislative districts—has played a significant role in America’s current political malaise and that existing reforms have done little to address the underlying problem.

“As the country has sorted geographically, with Democrats concentrating in cities and Republicans in rural areas, it is often impossible to draw competitive single-member districts that offer any semblance of geographic continuity and that keep communities of interest together,” the political scientists explained. “In fact, maps drawn by nonpartisan commissions in this redistricting cycle had just as few highly competitive districts as those drawn by politicians.”

Another advantage of proportional representation is that it results in legislative bodies that better reflect diverse communities. “At the level of narrow, winner-take-all districts, only the majority opinion gets represented and we appear divided between fully Democratic and fully Republican districts,” the political scientists noted. “But on the scale of our communities, regions, and states, the United States remains a diverse and complex political tapestry. In 2020, there were more Trump voters in California than any other state and more Biden voters in Texas than in New York or Illinois. The vast—even overwhelming—majority of Americans don’t fit precisely into the ideology of their single-member congressional representation.”

For a place as diverse as Los Angeles, proportional representation could result in a City Council that is more reflective of the city and its interests. At the very least, it would save L.A. from its current single-member district system and all the corrupt incentives that come with letting lawmakers choose the voters and communities that they represent instead of the other way around. One need not take reformers for their word on the flaws in the status quo. The Los Angeles City Council members on the recording have done that more effectively and eloquently than any reformer ever could.