Last

month, Chesa Boudin, the former district attorney of San Francisco, spoke with

the leftist podcaster and political commentator Katie Halper on YouTube

about the recall campaign that removed him from office in June. Soon after

taking office in January 2020, Boudin, a former public defender who had

promised a program of criminal legal reform, police accountability, and

decarceration, was held responsible for San Francisco’s crime and social

dysfunction by a coalition of business leaders, tech moguls, and even some of

his former subordinates at the district attorney’s office.

Speaking to Halper, Boudin gave a passionate defense of his policies, while also zeroing in on the moneyed forces arrayed against him. “There’s no limit to how much you can donate to a recall in San Francisco,” he said, “and it’s very easy to hide the true source of those funds.”

The interview wrapped up, but the conversation wasn’t over. Halper invited her audience to discuss on Callin, a growing podcast platform, “the astroturf recall” that removed Boudin. But there was a glaring, unacknowledged irony: Callin, which has attracted a swathe of very online journalists from the left, right, and murkier ideological corners, was co-founded by David Sacks, a venture capitalist and longtime tech executive who was one of Boudin’s earliest and most vocal opponents. Sacks had branded Boudin “the Killer D.A.” whose policies caused innocent people to die. He told former Fox News star Megyn Kelly that there was “chaos and lawlessness in San Francisco,” a product of “Soros D.A.s” with their “progressive agenda of decarceration.” He challenged Boudin to a public debate—“if you have the huevos,” Sacks said—and then accused him of backing out of an agreed upon appearance on All-In, the popular podcast Sacks co-hosts with fellow tech investors Jason Calacanis, Chamath Palihapitiya, and David Friedberg. Sacks was also one of the biggest recall donors; at one point in 2021, nearly one-third of all donations against Boudin came from him. Halper was trying to parse Boudin’s loss on a platform run by the man who had helped lead it. (“Under a system of global capitalism and tech monopolies, all platforms have owners,” Halper said. “But I don’t speak for them, and they don’t speak for me.”)*

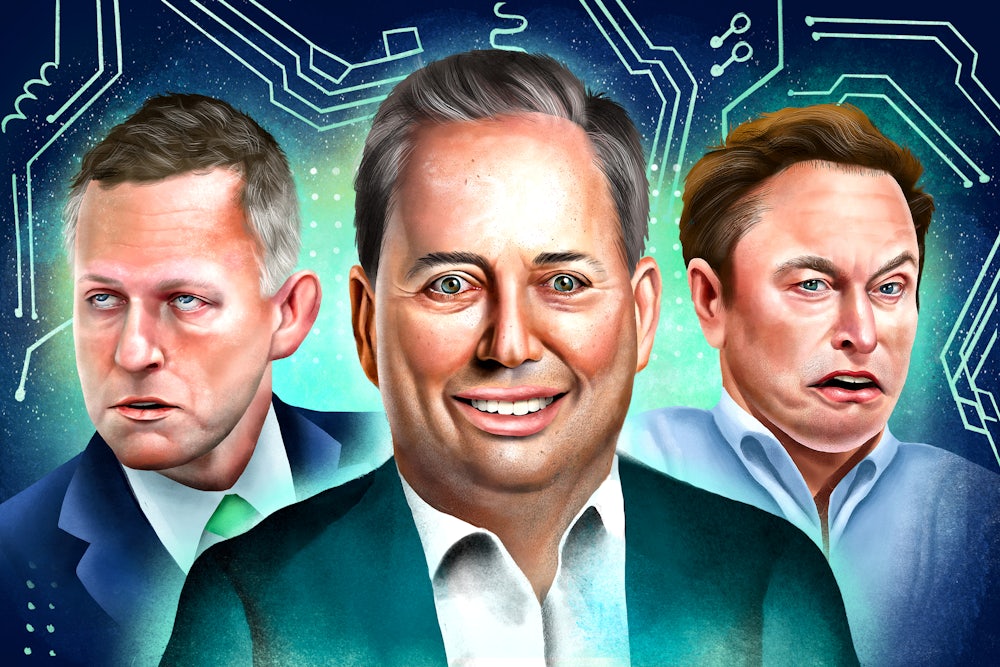

After serving as PayPal’s founding chief operating officer, followed by stints as chief executive of Yammer and Zenefits, Sacks, 50, now leads a venture capital firm called Craft Ventures. While not yet a household name like his pal Elon Musk, he’s a regular across conservative media and on Twitter, where he has more than 400,000 followers, and exerts a growing influence in the political battles playing out in the tech industry. Sacks is part of the Tesla CEO’s “shadow crew” of friends and consiglieri, according to The Wall Street Journal. Text messages that were recently disclosed as part of Musk’s legal battle with Twitter showed that Musk sent his friend Sacks a tweet by conservative huckster Dinesh D’Souza expressing support for Musk’s takeover of Twitter. Sacks said he retweeted it. In other messages, the two discussed a potential monetary contribution from Sacks for the Twitter acquisition. In early October, Musk proposed a negotiated settlement to Russia’s war in Ukraine that mirrored arguments Sacks had made in a piece a week earlier for The American Conservative. Political consultant Ian Bremmer later wrote that Musk said he had spoken with Russian President Vladimir Putin, who had influenced Musk’s peace offer. Musk denied Bremmer’s report. On Twitter, Sacks backed Musk’s proposal and argued that the backlash generated—for example, against Musk’s suggestion that Russia should be given the Ukrainian region of Crimea—was the product of a “woke mob” that, Sacks later wrote in Newsweek, would cause the next world war. In a tweet, Musk praised the Sacks piece as “exceptionally well-said.”

Sacks is quietly becoming the leading practitioner of a new right-wing sensibility that has emerged in the political realignments provoked by Trumpism and the pandemic. On foreign policy, it offers a blend of isolationism, Trumpist nationalism, suspicion of the deep state, and the anti-empire realism of John Mearsheimer. Domestically, the vision is more muddled, a series of angry poses, a politics of pique, much of it playing out on Twitter, Callin, YouTube, Rumble, Substack, and other online media, especially among people who may have once counted themselves on the left but now can’t countenance the sight of homeless encampments. It’s The Young Turks host Ana Kasparian dedicating an episode to “violent criminals being let off easy” in California; Jacobin columnist Ben Burgis calling critics of Kasparian’s reactionary takes on bail reform and other criminal legal system issues the “silliest scolds of the online left”; and Nando Vila, a Jacobin contributor and onetime host of The Jacobin Show, arguing that fighting false perceptions about crime is “definitely a losing battle, because all you have to do is see that it is real” in the form of homelessness, which has been increasingly criminalized.

These dissident leftists are joined by a growing number of tech and finance elites with reactionary politics. There’s billionaire William Obendorf, who also bankrolled the Boudin recall and is on the board of two anti-Boudin nonprofits, one of which paid Boudin replacement Brooke Jenkins $153,000, and Bill Ackman, a hedge fund manager and Democratic donor who praised Donald Trump’s election and became a dedicated defender of Kyle Rittenhouse. For a brief period in 2021, Clubhouse was the locus of these reactionary political currents—the hangout spot, really, for internet-famous venture capitalists and techies chafing against Silicon Valley’s traditionally liberal culture. Though the app didn’t sustain its early momentum, it inspired a number of imitators.

In the fall of 2021, Sacks launched Callin with $12 million in series A funding. Building on its predecessors, Callin offered both live and recorded audio discussions, podcast hosting, and ways for users to interact with hosts. The company made deals to bring aboard established journalists and podcasters, and the site’s sensibility quickly became defined by post-left, contrarian, or otherwise reactionary libertarian types such as Jesse Singal, Jimmy Dore, Glenn Greenwald, Michael Tracey, Briahna Joy Gray, and Matt Taibbi.* Many have taken on Sacksian talking points about unchecked urban crime and the alleged failures of defunding police that haven’t been defunded. Sacks himself has a now dormant Callin show called Purple Pills that featured guests like Boudin antagonist Michael Shellenberger, who sought to replace Gavin Newsom in the failed California gubernatorial recall, on “why progressives ruin cities.”

Sacks declined requests for an interview, both directly and through a representative. But his writings, media appearances, political donations, and professional network say a great deal both about his political rise and the way tech elites now exercise power.

Steeped in the inflammatory milieus of social media and Tucker Carlson demagoguery, Sacks and his fellow travelers often seem less to stand for anything than against the status quo—against criminal legal reform; against the public presence of homelessness; against a tradition of Democratic urban governance that, by indulging in identity politics, has failed to solve economic and social ills. They are angry, and they want the government, which they see as simultaneously incapable of doing much good, to work for them again.

Whether or not you buy into this doomer vision, it’s evolving into coherence, with increasing purchase in right-wing circles. This nascent movement’s talking points have the kind of blunt simplicity that, if not convincing, at least rack up retweets: Democrats are hysterically woke; liberalism has failed; drugs, crime, and homelessness are destroying cities; Black Lives Matter was only about riots. In this corner of the political imagination, crime, drug addiction, and homelessness are outrageous horrors—but mostly for how they threaten the daily peace of responsible, productive citizens. In an interview with Megyn Kelly on the day of the Boudin recall vote, Sacks said that the influx of fentanyl into the United States was China’s “payback” for the nineteenth-century Opium Wars, calling Democratic politicians “useful idiots for the Chinese Communist Party.”

This ethos was perhaps best described by Vice’s Edward Ongweso Jr. and Jason Koebler when they called this year’s mayoral race in Los Angeles the “Nextdoor Election,” referring to the social app that has become an epicenter for racist and classist complaints about crime and homelessness. It’s a draconian version of call-the-manager politics—it’s time to let the police, the custodians of capitalist order, do something.

The symbolic epicenter of this movement is San Francisco, but really it’s the entire curdled utopian dream of California. In the eyes of rich techies who have seen their beloved metropolis fall into decay, vast inequality, and social misery, the state is dead. Their disappointment and alienation has melded with traditional Republican disgust toward liberal cities (and their non-white residents) to paint a picture of irredeemable urban squalor. These frightened urbanites are echoing the Trumpist drumbeat that cities—particularly in California—are dangerous, dark places that must be tamed. But despite California’s violent crime rate increasing by 6 percent in 2021, the state’s violent crime rate (466 per 100,000 residents) is far lower than its 1992 peak of 1,115 per 100,000 residents.

A low point of this hand-wringing came in August, when Boudin recall backer Michelle Tandler issued wild-eyed warnings about San Francisco dogs becoming addicted to meth by eating feces. Tandler worked at social networking service Yammer when Sacks was its CEO, and she’s frequently praised him on Twitter, where she’s accumulated a large following as a blistering “anti-San Francisco influencer,” according to The San Francisco Examiner, even though she now resides in New York City. In 2020, Sacks’s Craft Ventures made a seed round investment in a Tandler-led startup called Life School, and they both made donations on August 6, 2021, to the campaign to recall three members of the San Francisco school board. In December 2021, Life School announced a pivot—from classes teaching basic life skills to “an audio-first company” offering interviews with “experts about basic life skills.” The new company, a Substack-hosted publication called Growth Path Labs, provides brief podcasts with titles like “How to Give Critical Feedback” and “How to Fire Someone (with Humanity).”

The godfather of the movement is Peter Thiel—the billionaire venture capitalist, Gawker slayer, leading Republican donor, early Trump backer, PayPal co-founder, and Palantir founder and chairman who has expressed his indifference, at best, to democracy. In his political disciples—and former employees—J.D. Vance and Blake Masters, Thiel has found candidates to run on his belief system, right-wing Christian nationalists who are pro-business, pro-gun, and able to cater to conservative culture warriors. Call it PayPal mafia politics. The extensive corporate and political network that began with Thiel, Musk, Reid Hoffman, Max Levchin, and other early employees of the payments company—not all of whom share the same right-leaning politics—includes the lesser-known Sacks, PayPal’s founding COO.

Despite Sacks’s ties to the online post-left and his efforts to speak for San Francisco’s disenchanted Democrats, his record of campaign finance donations tells the story of a die-hard Republican. Sacks has helped power the political ambitions of traditional Republican politicians as well as Masters and Vance. He also donated to Hillary Clinton in 2016 and more recently to Kyrsten Sinema, “once again sticking a thorn in the side of progressives,” according to the San Francisco Chronicle. In 2021, he gave $70,223 to Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. He also donated $60,000 to Republican Miami Mayor Francis Suarez’s Miami for Everyone PAC, whose lead donor is Sacks’s podcast co-host Chamath Palihapitiya.

Now, Sacks is set to push his political project, and his money, further. Over the summer, an organization called Purple Good Government PAC filed its first donor report. The PAC’s existence has yet to be widely reported, and his representative declined to answer questions about its plans, but the organization’s filings include people from Sacks’s network. The PAC’s treasurer is James Kull, a financial adviser who signed a mortgage for a Miami mansion purchased last year by an LLC whose address matched one used by Sacks. The PAC raised about $280,000 in the first six months of 2022, including $125,000 from Sacks and his wife. Three donors—EarthLink founder Sky Dayton, e-commerce entrepreneur Diego Berdakin, and the Dohring Family Trust—gave $50,000, with each entity giving separate payments of $5,000 and $45,000.

The PAC has dispensed about $135,000 so far, most of it in the form of a $100,000 donation to Friends of Ron DeSantis leadership. A representative for Sacks declined to say whether the venture capitalist would support DeSantis over Donald Trump in a 2024 Republican presidential primary, but the money talks. Last October, Sacks hosted a fundraiser for the Florida governor and once tweeted his hopes for a Newsom-DeSantis matchup in 2024. In a further indication of DeSantis’s close contact with this tight-knit group, the court-disclosed Musk texts included an exchange with Palantir co-founder and venture capitalist Joe Lonsdale, who said that DeSantis called him to offer help sealing Musk’s Twitter bid.

Under Thiel’s guiding example, Sacks is forming his own political donor network. Last December, he hosted a fundraiser for Vance. In April, Sacks donated $1 million to Protect Ohio Values PAC, which supports Vance. Around the same time, Trump endorsed the Hillbilly Elegy author. Both the donation and the endorsement were reportedly brokered by Thiel. On September 15, Sacks co-hosted a Republican fundraiser with fellow PayPal mafia member Keith Rabois. Guests included current GOP Senators Rick Scott, Marco Rubio, Chuck Grassley, and Republican candidates Masters, Mehmet Oz, and Vance.

Despite his contributions to Vance, Sacks has barely tweeted or written about him. His $1 million donation received little media attention. But in March, Sacks praised Vance’s calls for U.S. military restraint in Ukraine. “This is why I’m proud to support @JDVance1,” tweeted Sacks, rounding it out with a MAGA reference. “It’s time to put America first.”

Thiel and Sacks met at Stanford, where they worked together on the Thiel-founded Stanford Review. In 1992, the Review published “The Rape Issue,” which included a piece by Sacks defending a student who had pleaded no contest to statutory rape. Sacks considered the crime “a moral directive left on the books by presexual revolution crustaceans.” According to Thiel biographer Max Chafkin, “Sacks included a graphic description of the encounter, noting that the 17-year-old victim ‘still had the physical coordination to perform oral sex,’ and ‘presumably could have uttered the word, ‘no.’” Rabois, who later became Sacks’s PayPal colleague, was also a contributor to “The Rape Issue.” In 2013, Rabois resigned as Square’s COO after being accused of sexual harassment.

Later, Sacks and Thiel wrote op-eds about economics and politics for The Wall Street Journal, National Review, and the San Francisco Chronicle. In 1995, they published a book called The Diversity Myth: Multiculturalism and Political Intolerance on Campus. Angry, trollish, homophobic, fixated on identity and campus politics, The Diversity Myth could easily be produced today, with panic about “woke” culture substituting for every mention of multiculturalism, which is wielded throughout as a bitter epithet. In the book, Sacks and Thiel revisited the Stanford rape, writing that “a multicultural rape charge may indicate nothing more than belated regret.” (In the authors’ moral universe, almost anything can be derisively labeled as “multicultural.”) When the line resurfaced in Forbes in 2016, both Thiel and Sacks apologized, although the book contains plenty of other similarly minded sentiments. They accused sexual assault activists of vilifying men and promoting fraudulent “‘advocacy numbers,’ not real facts,” writing that “the rape crisis movement transmits its exaggerated fears to freshmen yearly.” The Diversity Myth was a deeply political book—not only in its screeds against multiculturalism and sexual assault education—but also in its production. It was sponsored by the Independent Institute, a libertarian think tank, and it was helped by Republican operatives and politicians of the era. The authors acknowledged the advice of Tom Duesterberg, who was Vice President Dan Quayle’s chief of staff; a former FCC commissioner; congressional staffers; and conservative political theorists, think tankers, and economists. They also announced that “a special thanks goes to Keith Rabois and the other victims of multiculturalism interviewed for this book.”

In 1992, while a first-year law student at Stanford, Rabois and two friends stood outside the home of a university lecturer and yelled homophobic slurs. Representative comments included: “Faggot! Hope you die of AIDS!” Afterwards, Rabois wrote to The Stanford Daily, “The intention was for the speech to be outrageous enough to provoke a thought of ‘Wow, if he can say that, I guess I can say a little more than I thought.’”

Stanford’s administration basically conceded the point: The school condemned Rabois’s behavior, saying that “this vicious tirade is protected speech.” There was a lot of outrage, letter writing, and some campus struggle sessions about misogyny and bigotry within Stanford’s institutions—genuine attempts at social critique that are duly made fun of in The Diversity Myth. But there was no formal effort to punish Rabois. Instead, after becoming locally infamous, Rabois transferred to Harvard Law School, before moving on to PayPal and a successful tech career that made him fabulously wealthy. In the long tradition of conservative victimology, that makes Rabois a martyr.

Sacks’s

early success at PayPal was naturally linked to Thiel, the company’s founding

CEO. Sacks grew wealthy and powerful as part of the same tech and political

networks for which Thiel and Musk are now leading figures. Sacks’s net worth

hasn’t been reliably reported in public. Besides the Miami mansion worth $17

million, he owns a $23 million Hollywood Hills home and a $20

million home on San Francisco’s “Billionaires Row.” In addition to a fortune

made as an executive, he’s a crypto investor who bought early into Solana, a

popular crypto token.

Sacks has said that his political views have “evolved” from libertarian to “populist.” In a podcast interview with Bitcoin influencer Anthony “Pomp” Pompliano, Sacks said he had “working-class views” in line with a transforming Republican Party. He cited the work of Ruy Teixeira, a liberal political scientist who co-authored the influential book The Emerging Democratic Majority with John B. Judis, but recently joined the American Enterprise Institute, after arguing that Democrats’ “professional class hegemony” has made the party out of touch with working people’s concerns. Or, as Sacks describes it, everything is run by Democrats with college degrees, who enact “the tyranny of woke progressivism.” Even big corporations, Sacks tweeted, are run by Marxists, echoing the long-held belief of DeSantis that companies like Disney promote a “woke ideology.”

Like others in his tech orbit, Sacks is deeply concerned about perceived threats to online speech. A supporter of Musk’s Twitter takeover, he’s argued for a less-moderated Twitter, free from the censoriousness that conservatives accuse tech companies of cultivating. In an April interview with Fox News, Sacks said that we are living in a McCarthyist moment of “un-American movements’’ to stymie free speech. Comparing Musk’s proposed purchase of Twitter with the fall of the Berlin Wall, Sacks said, “It was the first time that you saw somebody stand up to this galloping wave of censorship that we’ve been seeing.”

But

while Sacks’s project and carceral sensibility have scored victories including

Boudin’s recall and the successful launch of Callin, it’s now facing

significant headwinds. In August, Los Angeles District Attorney George Gascón,

a progressive prosecutor in the Boudin mold, survived a second recall attempt. Trumpist

reactionaries like Masters and Mehmet Oz are locked in tight races and Doug Mastriano,

running for Pennsylvania governor, will probably lose. Thiel is quickly burning goodwill with Republican leaders

like Mitch McConnell—though Vance may limp over the finish line. Few

people beyond the right-wing technorati seem to take seriously Curtis Yarvin,

Thiel’s monarchist court philosopher and the de facto

intellectual grise of this movement, who once said that America should be run

in a manner that “feels like a startup.” That seems like a dim prospect when

recent Thiel-funded startups—a Candace Owens–endorsed “anti-woke bank” and a conservative dating app started by a Trump

appointee reportedly investigated by the Department of

Homeland Security for financial crimes—have teetered between online mockery

and outright failure.

For now, there are some loud, rich, and very online players espousing these

ideas—with support from some corners of the GOP, and most recently

Tulsi Gabbard, who announced her departure from the Democratic Party

by denouncing its adherents for their “cowardly wokeness,” “anti-white racism,”

and their tendency to “demonize the police but protect criminals at the expense

of law abiding Americans.” But their ability to appeal beyond their cohort may

be limited—can it scale?

Thiel, at least, seems to be shifting his focus to this question of political pragmatism—and perhaps a rejection of Sacksian doomerism. Speaking before the National Conservatism Conference on September 11, Thiel called for Republicans to find a “positive agenda” to present to the public, one that can “scale” beyond their own cloistered group of similarly aggrieved conservatives. “The temptation on our side is always going to be that all we have to do is say that we’re not California,” Thiel said. “It’s such an ugly picture, it’s the homeless poop people pooping all over the place, it’s the ridiculous rat-infested apartments that don’t work anymore, the woke insanities, there’s so much about it that it feels like … shooting fish in a barrel. It’s so easy, so ridiculous to denounce.”

In the same speech, Thiel praised Ron DeSantis as “offering a real alternative to California,” but worried that rising home prices in Texas and Florida meant that these supposed alternatives were replicating California’s mistakes. Instead of addressing these issues, Republicans were performing their congenital form of what Thiel called “nihilistic negation”—that is, the kind of reactionary obstructionism that has helped bring us to this point. In an age of widespread political cynicism, it plays well on social media, which privileges conflict and sensationalism.

The sort of social media envisaged by Thiel, Sacks, Musk, and other tech moguls might come to fruition if Musk’s bid to acquire Twitter closes, per a judge’s ruling, by the end of the month. It will also be a boon to Musk’s friends who invested in and supported the takeover. The recently disclosed text messages showed Musk being peppered with pitches about rejuvenating Twitter from PayPal mafia members and sycophantic hangers-on. In one set of messages, in which names were redacted, someone discussed letting “the boss himself”—Trump—back on the platform. The comments included some war-gaming and bluster about deplatforming political enemies. Masters was floated as a so-called VP of Enforcement. If there is to be a new regime adjudicating speech on Twitter—which would be set to go private under Musk’s ownership, removing it from certain corporate disclosure requirements—it might be overseen by people like Masters who share the same worldview as Sacks.

The positive, Sunshine State–style program promised by Thiel in his September speech has yet to materialize—DeSantis is currently in federal court defending his decision to suspend progressive prosecutor Andrew Warren for pledging not to prosecute abortion-related crimes. And Sacks is still in thrall to urban pessimism, a stance popular in San Francisco where Mayor London Breed recently said—to applause from a crowd—that drug dealers have more rights than “people who try to get up and go to work every day and take their children to school.” The day after the Boudin recall, Sacks went on Tucker Carlson to celebrate his victory and denounce the Democrats’ radical agenda of “decarcerationism.” Carlson credited Sacks with funding the recall and allowing “democracy to take place.” Sacks explained that Democrats and their “woke billionaire” supporters—George Soros, Reed Hastings—were deeply committed to the decarceral program, so it would be necessary to take the fight elsewhere. “This sort of playbook here is going to have to be replicated across the country.”

This article has been updated with a quote from Halper.

* This article originally stated that Benjamin Norton had an active contract with Callin.

This story was produced in partnership with the Garrison Project, an independent, nonpartisan organization addressing the crisis of mass incarceration and policing.