In July, President Joe Biden swallowed his pride and bumped fists with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who, four years earlier, directed the murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. One of the killers was a forensics expert named Salah Muhammed Al Tubaigy. According to a report in a Turkish newspaper later cited by The Washington Post’s then editorial page editor, the late Fred Hiatt, Al Tubaigy started dismembering Khashoggi on an autopsy table before Khashoggi was even dead. Before applying his bone saw, Al Tubaigy slapped on earphones because, he explained to his fellow assassins, “When I do this job, I listen to music. You should do [that] too.”

In an elaborate judicial pantomime, the Saudis tried Al Tubaigy in secret, sentenced him to death with four others, then pardoned all five at the “request” of Khashoggi’s adult children—who, because they maintained ties to Saudi Arabia, and because they accepted money for their silence, were not free to dispense mercy on their own terms. All this was known during Donald Trump’s presidency. His response was to cast doubt (“maybe he did and maybe he didn’t”) on whether bin Salman ordered the killing. “I saved his ass,” Trump later boasted to Bob Woodward about the crown prince. “I was able to get Congress to leave him alone. I was able to stop them.”

Biden, unlike Trump, accepted the judgment of U.S. intelligence that bin Salman directed the killing. As candidate, he pledged to make bin Salman a “pariah.” As president, he released an intelligence assessment that assigned blame to bin Salman; imposed economic sanctions and visa bans on a few high-ranking Saudi officials; and waited 20 days after assuming office—which isn’t very long—before talking to Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, Saudi Arabia’s nominal but senile monarch. Biden excluded from the phone call bin Salman, who is Saudi Arabia’s de facto monarch.

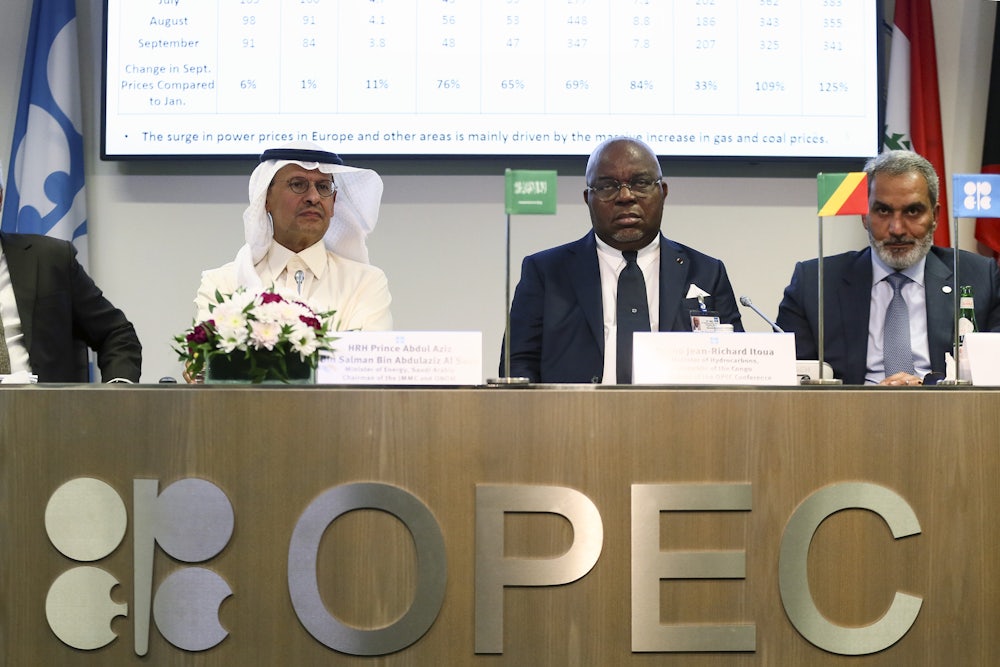

This moral stance was gratifying, but it was no more sustainable than the presumed desire of Salah, Abdullah, Noha, and Razan Khashoggi that their father’s killers be punished. That’s because Saudi Arabia possesses 17 percent of the world’s petroleum reserves and leads an illegal but powerful international oil cartel known as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. Biden bumped fists with the crown prince because the United States needed oil to keep flowing while Russian President Vladimir Putin waged war in Ukraine.

On Wednesday that fist bump was answered with what’s being described (by Biden sympathizers) alternately as a “slap in the face” (David A. Andelman, CNN), a “spitting in the face” (economist Dean Baker, quoted in The Washington Post), and a “gut punch” (Eugene Robinson, Washington Post). OPEC announced it would cut oil production by two million barrels a day. That immediately pushed up the price of benchmark Brent crude to $93 a barrel. By the end of last week, Brent Crude was selling at $98.45 a barrel.

The Saudi slap inspired calls in Congress to pass the No Oil Producing and Exporting Cartels Act, or NOPEC, a bill first introduced by then-Senator Herbert Kohl, a Wisconsin Democrat, in 2000, and reintroduced in just about every Congress since. The bill would clarify that neither the doctrine of sovereign immunity, which bars lawsuits against foreign nations, nor the “act of state” doctrine, which bars lawsuits against expropriation by foreign nations, prevents the Justice Department from busting OPEC, just as it routinely busts other international cartels. It has been doing so at least as far back as 1907, when it shut down a tobacco cartel that included two British firms. The Supreme Court affirmed in 1911 that the Justice Department had every right to prosecute foreign members of international cartels. Since 1995, according to the Justice Department, the antitrust division “has given top priority to aggressive enforcement against international cartels.” The lysine livestock-feed-additive cartel—busted! The citric acid food-additive cartel—busted! The graphite-electrode-for-steelmaking cartel—busted! The vitamin cartel—busted! Japanese nationals, German nationals, and Swiss nationals were all prosecuted, and some went to jail. We even prosecuted somebody from Canada, our friendly neighbor to the north. But participants in the world’s single biggest cartel, OPEC, walked free, escaping even civil penalties.

There are two central facts about NOPEC. The first is that it’s wildly popular; I don’t think it’s ever lost a single vote. The second is that in spite of its popularity, it never becomes law. Presidents Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden all supported NOPEC as candidates. So did candidate Hillary Clinton. But once entering office, Obama, Trump, Biden, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton all poured cold water on NOPEC as too irresponsible.

NOPEC cleared the House Judiciary Committee in April 2021, and it cleared the Senate Judiciary Committee in May. Senator Chuck Grassley, the Iowa Republican who’s led the NOPEC charge for the past few years, says he’ll try to attach it to the forthcoming defense appropriation bill. The Biden administration is so pissed off at bin Salman that it’s signaled it may be willing to support NOPEC, provided (this is the unspoken part) it can find some way to keep it from taking effect.

The press has always treated NOPEC with condescension, without ever really expressing what’s substantively wrong with it. The only thing substantively wrong with it, so far as I can tell, is that even under current law, neither sovereign immunity nor the “act of state” doctrine ever barred the Justice Department from busting OPEC. The 1976 Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, or FSIA, states explicitly that sovereign immunity does not apply when the action is based “upon a commercial activity carried on in the United States by the foreign state” or “upon an act outside the territory of the United States in connection with a commercial activity of the foreign state elsewhere and that act causes a direct effect in the United States.” The illegal act in question doesn’t have to occur in the U.S. It can occur, for example, in Vienna, city of Strauss waltzes and Sacher tortes and coffee in tall glass mugs mit schlag, where OPEC finance ministers meet twice yearly at the cartel’s headquarters on the Helferstorferstrasse.

In the 1970s, when the 1973 Arab oil embargo and the 1979 Iranian Revolution sent oil prices into the stratosphere, people were forever urging the Justice Department to bust OPEC, but it wouldn’t budge. Finally the International Association of Machinists, under the feisty leadership of William Winpisinger, filed suit. OPEC’s lawyers (who included a promising young conservative named Antonin Scalia) argued that sovereign immunity protected OPEC. Judge Herbert Young Cho Choy of the Ninth Circuit, recognizing that the FSIA had made mincemeat of that defense, opted instead to throw out the Machinists’ suit based on the “act of state” doctrine.

The “act of state” doctrine is a fairly anodyne principle articulated by the Supreme Court in Underhill v. Hernandez (1897), a case brought by an American waterworks contractor who was affronted that the Venezuelan government made him wait five days after a revolution before it would permit him to leave the country. The high court in essence said What the hell do you expect us to do about it? The passage cited by Judge Choy was: “Every sovereign state is bound to respect the independence of every other sovereign state, and the courts of one country will not sit in judgment on the acts of the government of another done within its own territory.” Very reasonable. But OPEC is not a sovereign state, and Austria, where the OPEC finance ministers commit their crimes, is foreign territory to all of them. Judge Choy interpreted the “act of state” doctrine way too broadly to mean that “the courts should not enter at the will of litigants into a delicate area of foreign policy which the executive and legislative branches have chosen to approach with restraint.”

The function of NOPEC is to alert the courts that they have the power to apply U.S. antitrust law to OPEC and that they should not use some imagined prerogative of Congress and the president as an excuse not to do so.

NOPEC makes good sense. The trouble is that Congress and the president are willing to consider its passage only during maximally inopportune moments like the present. When oil is scarce, as it is now, people get mad at OPEC, and NOPEC is resurrected to appease them. But a time of oil scarcity is the absolute worst moment to get tough with OPEC, because OPEC can be counted on to retaliate by cutting production further, crippling Western economies. In such times, some way is always found by Congress or the president not to enact NOPEC.

The time to pass NOPEC is when oil is plentiful. But when oil is plentiful, Congress and voters are no longer mad at OPEC, and they forget all about it. The cycle reminds me of a character in Tom Stoppard’s play Albert’s Bridge who, despairing of humanity, climbs the titular bridge intending to commit suicide by jumping off it. When he reaches the top, though, he discovers, on surveying humanity from so great a height, that it possesses an order and beauty not visible from ground. So he climbs down, reimmerses himself in ground-level misery and chaos, succumbs to despair again, climbs up again, etc., ad infinitum.

The time to kick OPEC, I wrote back in 2001, and reaffirmed in June, is not when it’s up but when it’s down: When gas prices are low and the American Petroleum Institute is begging Congress for tax breaks. We’ve experienced this multiple times since NOPEC was first proposed in 2000. But we’ve always missed our chance. I applaud the impulse to break the oil cartel, avenge the brutal death of Jamal Khashoggi, and give the Saudis a well-deserved slap back. But the moment to act is when no one is brooding about such matters.