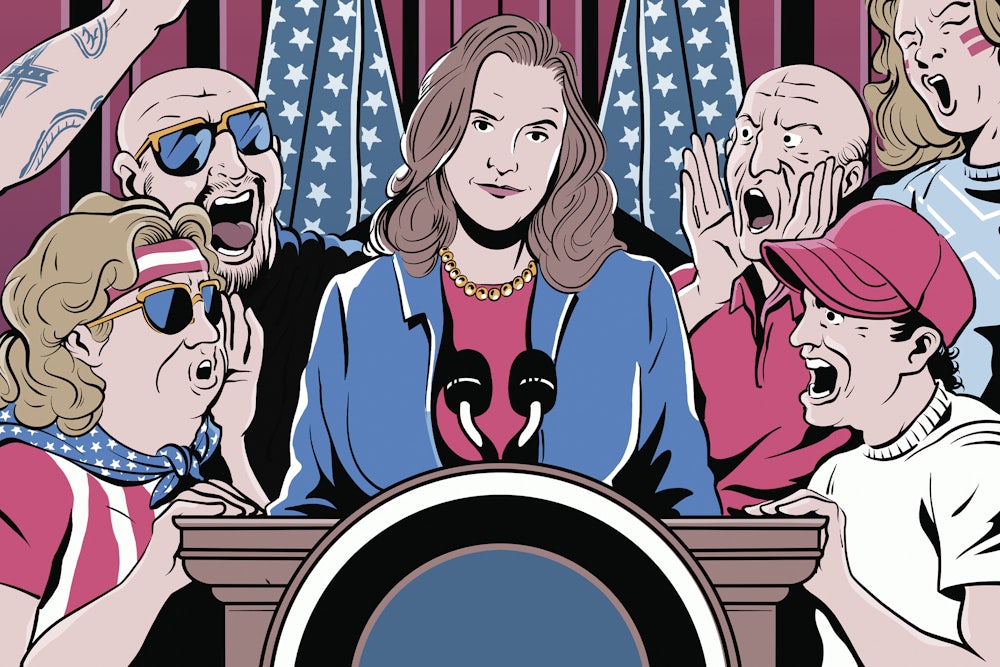

The story of Democrat Gretchen Whitmer’s gubernatorial reelection in Michigan is one that might sound more like a Netflix political thriller than a midterm campaign. She was one of those prudent governors who initiated strict lockdowns early in 2020 when Covid-19 hit and stuck to them even as other states eased restrictions. The backlash among her critics in Michigan was severe. They nicknamed her the “Wolverine Queen,” and not as a compliment. Her anti-coronavirus moves spurred a group of conspirators to cobble together a harebrained plot that was half Coen brothers film, half militia nightmare: They’d kidnap the governor to trigger a national civil war. The scheme was thwarted by the FBI, but the trial that followed offered equally bizarre developments, such as the plotters hiring a private investigator to search for dirt on one potential juror.

Ever since Whitmer became governor in 2019, she has been regarded as a rising star, someone who local Democrats suspected might run for president one day. The larger Democratic Party seemed to embrace this prospect, maybe not for 2020, but perhaps 2024, 2028, or beyond. Joe Biden vetted Whitmer as one of the finalists to be his vice president. In early 2020, she gave the Democratic response to Donald Trump’s final State of the Union address—a job usually granted to someone whom elected officials want to elevate as a future face of their party.

It’s easy to see why Whitmer appealed. She hails from the Rust Belt region, once a Democratic stronghold, but now an area in which the party has been losing traction. And at 51, she’s decades younger than most of the party’s leadership. When she’s in office, she has an ease and charisma that’s hard not to like (though that comes out more when she’s legislating than when she’s on the campaign trail). Her focus on “fixing the damn roads” is an argument that transcends the usual topics of partisan rancor. When she ran four years ago, she won by nearly 10 percentage points.

But amid the madness of the past few years, she saw her public support drop—a dip in public standing that coincided with generally dim prospects for Democrats in the 2022 midterms. The phrase “red wave” was regularly recited in Washington political circles. Republicans were essentially measuring the drapes in both chambers of Congress. The mood was equally dim among the 22 Democrats sitting in governor’s mansions across the country.

Things were no different for Whitmer. It wasn’t so long ago that Michigan had a two-term Republican governor. Republicans can and still do win in Michigan—Trump narrowly carried the state in 2016, and Joe Biden had a less than 3 percentage point edge in 2020. The possibility of Whitmer being a one-term governor hadn’t escaped her mind.

But fast-forward to final months of the campaign, and Whitmer’s situation isn’t as it once was—and neither is the political dynamic of the country. To the casual observer, everything that might have gone right for Whitmer seemed to have fallen into place, setting up what should be an easy election night in November. Rather than facing an opponent with appeal to moderates and maybe even some disenchanted Democrats, she has only to beat someone who energizes the fringiest wing of Michigan Republicans, someone over whom she is strongly favored. And few politicians were as ready to latch on to the new threat to reproductive rights. Whitmer acted quickly to protect abortion access in Michigan after Roe was overturned, while her opponent has vowed to weaken abortion rights as much as possible.

Since 1988, Michigan has only gone for the Republican nominee for president once. Nevertheless, it’s been considered a battleground state all the while. If anything, Republicans took Trump’s 2016 win as a sign that the right kind of candidate can activate a silent majority of very conservative base voters.

In recent years, Michigan Republicans have moved away from the technocratic lawmakers who usually represented their party and toward radicalized outsiders who energize the base while frightening everyone else. In 2018, Whitmer defeated Attorney General Bill Schuette, a lawmaker who served in the state legislature, as a judge, and as director of the Michigan Department of Agriculture. His loss seemed to rebut the idea that more establishment Republican types could win and succeed in office. (The last Republican governor, Rick Snyder, who ran his first campaign with the tagline “one tough nerd,” is still dogged by his handling of the Flint water crisis.) Today, the Michigan Republican Party is co-chaired by Meshawn Maddock, an outspoken conservative who rallied against Whitmer’s stay-at-home order during the darkest days of the pandemic. She is the kind of party chair eager to indulge Donald Trump’s false claims about the 2020 election and root out anyone who doesn’t pledge fealty to MAGA.

This year’s gubernatorial race initially included over a dozen Republicans. But the presumptive early front-runner was James Craig, an African American former Detroit chief of police. Early polling showed Whitmer with a 1-point margin against Craig. But things began to change dramatically around May, when a state canvassing panel disqualified five of the declared gubernatorial candidates.

That decision was prompted by complaints filed to the state from two separate corners of the state’s politics: former Michigan Democratic Party chair Mark Brewer and the Michigan Strong PAC, a conservative outside group aligned with political commentator–turned–Trumpy gubernatorial candidate Tudor Dixon.

During their review, election officials found thousands of fraudulent signatures by the campaigns, including those of Craig and Oakland County businessman Perry Johnson, the two candidates who seemed most formidable against Whitmer. Both were kicked off the ballot before the Republican primary. Dixon won with about 41 percent of the vote.

Then, a month later, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Reproductive rights have been a central focus throughout Whitmer’s career as a legislator, going back to her days in Michigan’s House of Representatives and state Senate. Whitmer’s first taste of visibility on the national scene came in 2013, when she recounted her own personal experience with reproductive care as she opposed a measure that would ban insurance plans covering abortions. “I’m about to tell you something that I’ve not shared with many people in my life,” Whitmer said, fighting to keep her voice steady on the Senate floor. “But over 20 years ago I was a victim of rape. And thank God it didn’t result in a pregnancy because I can’t imagine going through what I went through and then having to consider what to do about an unwanted pregnancy from an attacker.”

After her time in the state legislature ended in 2015, Whitmer’s political future was unclear—until Ingham County Prosecutor Stuart Dunnings III was arrested and charged with almost a dozen counts involving a prostitute and another four of willful neglect of duty. Whitmer was selected to fill out the rest of Dunnings’s term, keeping her in the Michigan political mix.

When she ran for governor a few months later, Emily’s List was an early endorser. Now, with Roe overturned, abortion access was once again front and center for her legislative agenda. In the months after the Dobbs ruling, Whitmer jumped to action. Her administration immediately sought a preliminary injunction against enforcing a 1931 law banning abortion. It filed a restraining order to block county prosecutors in Michigan from arresting abortion providers. She urged major tech companies not to allow personal data to be “weaponized” against women seeking abortion.

In early September, the Michigan Court of Claims agreed with Whitmer’s administration and ruled that the old law banning abortion was unconstitutional. Whitmer’s state would remain one that allowed abortions. “I have been fighting like hell to protect reproductive freedom in Michigan for months,” Whitmer said, “and am grateful for today’s lower court ruling declaring our extreme 1931 abortion law unconstitutional.”

“The campaign and the governor were very smart to really get out in front of the decision and sue here in state court to try to block the 1931 law from going into effect,” said former Michigan Democratic Party chair Brandon Dillon. “And then [they] just continued to be really smart and understand how powerful this issue is and how much it’s motivating not just Democratic base voters but also appealing very strongly to the same kind of independent suburban women and others who she needs to put together the coalition she had in 2018.”

By September, Republicans had settled on their nominee—Dixon, the kind of candidate Trumpian conspiracy theorists would dream of emerging from a secretive hard-right lab. She has publicly said that Donald Trump won the 2020 election and adamantly opposes abortions in almost all situations. “I know people who are the product [of that],” Dixon said when asked in an interview about a hypothetical 14-year-old rape victim who became pregnant. She stuck by her stance that there shouldn’t be any exceptions in abortion bans outside of medical necessity for the life of the mother. “A life is a life for me.”

On September 8, the Michigan Supreme Court ordered that a state constitutional initiative that would directly guarantee abortion access must be on the ballot in November—ensuring abortion would stay a major topic for the state’s midterms. Democrats hailed that decision. With strained logic, Dixon tried to play it off as a win for her. “And just like that you can vote for Gretchen Whitmer’s abortion agenda & still vote against her,” Dixon tweeted.

Since securing the nomination, Dixon has struggled in fundraising. Polls have shown her lagging behind Whitmer by as much as 16 percentage points, an even larger margin than Whitmer won with in 2018. In the final months before the election, Whitmer has dominated TV advertising. According to figures obtained by The New Republic, as of late September, Whitmer’s reelection campaign had spent $12 million on advertising, while Dixon’s campaign spent only about $130,000. (Though ads from outside groups have helped close that gap.)

While things could still change ahead of Election Day, Whitmer likely wouldn’t have wished that history turned out this way, even if it improved her political standing. She didn’t hope the Supreme Court would overturn Roe. She never would have wished the world would become afflicted with a deadly pandemic. And she did not pray that some of her most extreme critics would clumsily plot to kidnap her.

All of these events were deadly serious. They were also developments that presented Whitmer as both a sympathetic figure and a guardian of important, basic rights for Michiganders—women in particular. And if she does win her reelection campaign, it would further cement her status as one of the small group of Democrats under the age of 70 who have the checked boxes that people in her party look for in a presidential candidate.