John Fetterman was the poster dude for “green jobs“ during the first year of the Obama administration—that brief window of time when that administration seemed excited to address the climate crisis. As mayor of Braddock, Pennsylvania, a once-prosperous town that has never recovered from the exodus of the steel industry from the area, Fetterman starred in a 2009 video for an Environmental Defense Fund campaign called “Carbon Caps = Hard Hats.” Wearing work boots, he argued that a cap on carbon pollution would, by spurring growth in renewable energy, bring jobs to places like Braddock. He made similar arguments for green manufacturing on the floor of the House that year.

At the time, Fetterman was little known, and so was the idea of the “green economy.” (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was still in college, and the Green New Deal was years away from becoming a popular rallying cry, much less a set of demands.) But as a regular-seeming fellow representing a former steel town, Fetterman brought a kind of mainstream credibility to the idea that environmentalism could be worker-friendly. Although hardly blue-collar—Fetterman comes from a well-off family and has a master’s in public health from Harvard’s Kennedy School—he has a more populist vibe than most American liberals. That’s partly because he looks and acts like many American men. Unlike other Democratic boy wonders (John Edwards, Beto), he cannot be dismissed on the grounds of insipid good looks. He wears sweatshirts and shorts in any weather, has tattoos, has openly discussed his struggle with obesity, speaks bluntly. On a good day, he’s also funny. Men can see themselves in him, which is helpful when running against a Trumpist. And his values and political priorities are broadly shared: raise the minimum wage, stand up to corporations, fight the extremist Republicans.

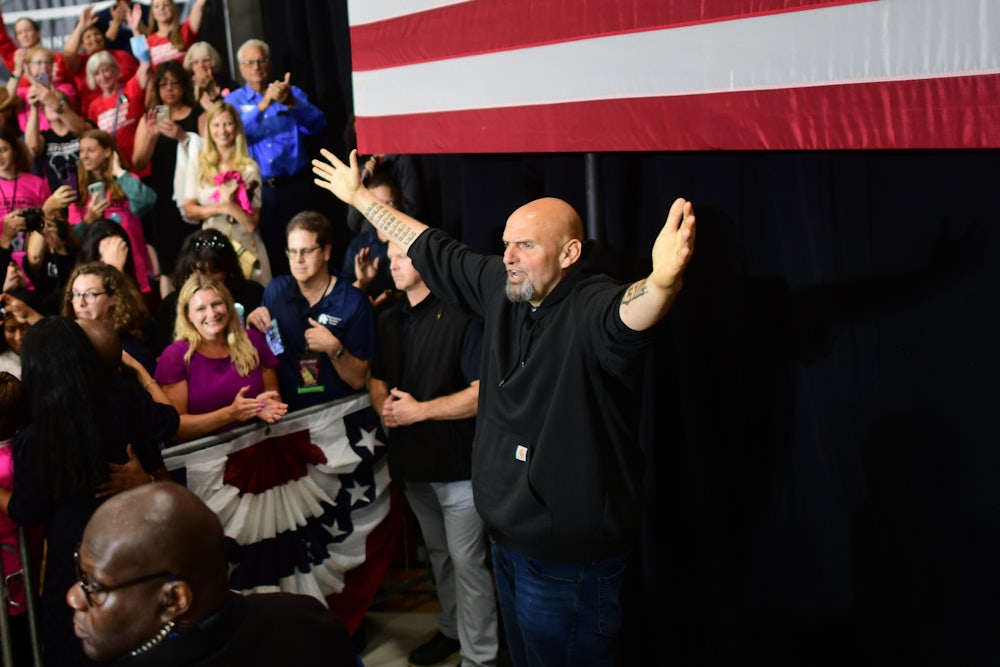

Now Fetterman has brought his winning persona and fine political communication talents to his Pennsylvania Senate race against Dr. Oz, a Trump supporter, a merchant of health quackery, and, what’s more, a resident of New Jersey. Fetterman’s Twitter mockery of an out-of-touch Dr. Oz ad on inflation—in which Oz misstated the name of the popular grocery store chain he was in and proceeded to buy asparagus and guacamole for cocktail hour—reduced that silly millionaire celebrity to a one-word joke: “crudités.” Further stunts by Fetterman’s campaign have included an ad with Jersey Shore star Snooki joking about Oz’s state residency, as well as an antic Fetterman has called “aerial trolling”: a big banner flying from a plane over the Jersey Shore welcoming Dr. Oz “home” to New Jersey.

Sadly, however, Fetterman hardly talks about climate or clean energy anymore. It’s a missed opportunity, especially given how much attention his Senate race is getting.

That may be because some of Fetterman’s environmental positions have changed, whether to attract more centrist voters or big donors: He no longer discusses carbon caps, nor does he support a moratorium on fracking.

Fetterman is leading Dr. Oz in the swing state, despite a debilitating stroke that has made it difficult for him to campaign in person. Many centrist Democrats would probably agree with his decision to avoid climate, which some in the consultant class view as a niche, polarizing “culture war” issue. Fetterman has excelled at focusing on popular priorities like marijuana decriminalization.

Yet all the evidence shows that 2009 Fetterman would be a huge hit today. Climate change is a big concern in swing states, including Pennsylvania, the Environmental Voter Project found in a large survey of registered voters in such states this summer. Likely voters in swing states who were either liberal, Democratic, moderate, or independent all rank climate among their top-three long-term priorities. And talking more about climate could bring more Pennsylvanians out to vote. In Pennsylvania, the EVP’s survey found, “low propensity” voters (those less inclined to vote in midterms) were more than twice as likely as “high propensity” voters to vote for a candidate based on their climate politics.

What all this suggests is that, as well as Fetterman is doing now, a green jobs message could widen his lead. He hasn’t neglected the climate entirely: His website mentions that we can create good union jobs in the transition to clean energy, and he’s got an anodyne campaign ad on “climate justice”—sort of a sleepy NGO catchphrase at this point, although the issue it refers to is important. But Fetterman could make much more of the transformative economic potential of clean energy in his popular Twitter account, his YouTube channel, and in media appearances.

Even if it wasn’t such a clear winning issue, talking more about climate would be the right thing for Fetterman to do. The climate crisis is urgent—as Hurricane Ian’s devastating toll on Florida already shows—and given his considerable skill as a communicator, and the attention his campaign has attracted, Fetterman is well positioned to educate people.

Fetterman’s temperament is needed in climate politics. The climate movement needs more people with Fetterman’s sense of humor and relaxed, irreverent affect. Doom and apocalypse, not surprisingly, aren’t popular. Nor is scolding us about our personal habits. None of that is Fetterman’s style.

He also has an easy and nontoxic masculinity that could help him push back against the gendered culture war the right is waging on environmental policy: Trump and others have been successfully exploiting gender anxieties by framing climate as a concern for effete sissies, mobilizing “petrosexuality.” Fetterman, a former football player who could bench-press 400 pounds in his youth, can’t be accused of being part of this feminizing liberal conspiracy. Of course, neither his athletic achievements nor his oddly typical male habit of wearing shorts in all situations should matter, but we are living in silly times.

Whether or not Fetterman talks about climate, I hope he wins. The climate needs another Democrat in the Senate, Fetterman has a record of much-needed compassion on criminal justice issues, and besides, Dr. Oz believes that “the ideology that carbon is bad is a lie.” But as gifted as Fetterman is at politics, underplaying the environment as the winds and rains batter Florida is a mistake.