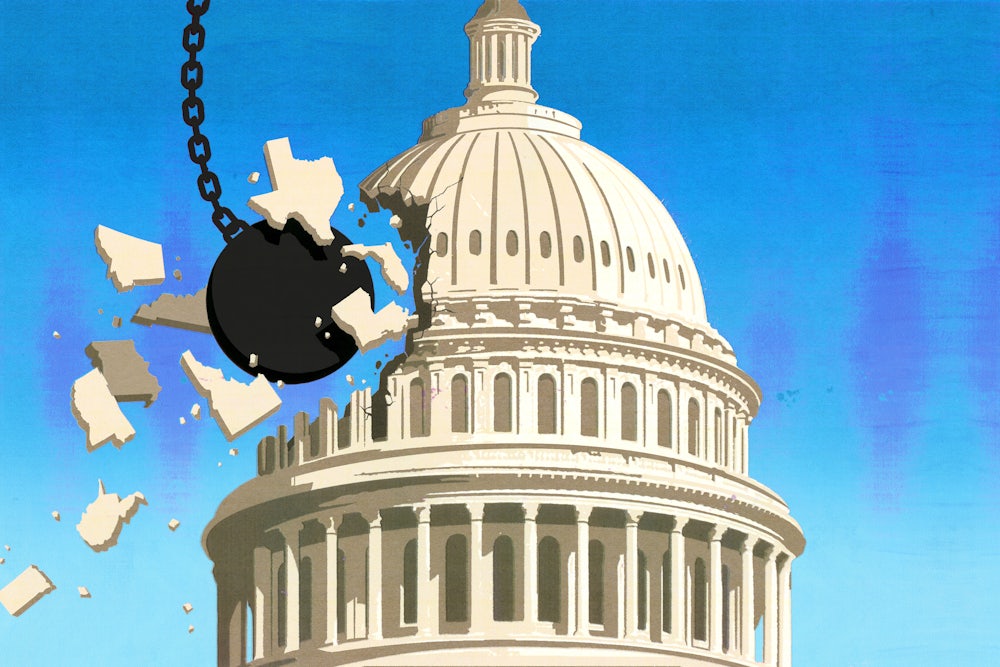

Once upon a time, all politics was local. These days, it seems, all local politics is national. And as the states grow further and further apart on policy, and the Republican Party’s opposition to democratic institutions grows more extreme, the downsides of federalism become ever more apparent. On episode 53 of The Politics of Everything, hosts Laura Marsh and Alex Pareene speak with Jacob Grumbach, the author of Laboratories Against Democracy, and Aaron Kleinman, the director of research at the States Project, about the ways our decentralized system threatens democracy, how the right and the left have responded to the increasing nationalization of politics, and what’s at stake in local elections during this year’s midterms.

Alex Pareene: Earlier this summer, two contrasting stories of state transportation policy caught my attention. As more than a dozen states made plans to join California in phasing out sales of new gasoline-powered cars, Republicans in North Carolina unveiled a proposal to effectively ban free charging stations for electric vehicles. It was a silly, almost trolling policy—which made it a perfect illustration of modern federalism, our system of local control, in action.

Laura Marsh: In the United States today, which side of the Colorado-Kansas border you reside on determines whether you can purchase legal cannabis from a well-appointed dispensary or whether a first-time marijuana possession charge might land you in jail for six months.

Alex: Teachers in Oklahoma are suspended for sharing links to libraries in New York.

Laura: As states run by Democrats have moved to expand access to health care and the ballot, states run by Republicans have heavily restricted both.

Alex: The Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade and the widely varying state abortion restrictions the decision enabled made clear what some researchers have been arguing for years: State governments haven’t been this powerful—and this far apart in governance—for a generation.

Laura: But as the disparities in policy among the states grow larger, our news media, political donations, and electoral cycles are more nationalized than ever.

Alex: The old saw that all politics is local looks increasingly out of date. In the twenty-first-century U.S., all local politics is national. I’m Alex Pareene.

Laura: And I’m Laura Marsh.

Alex: This is The Politics of Everything.

Laura: We’re talking now with Jacob Grumbach, the author of the new book Laboratories Against Democracy. Jake, the title of your book is a play on the idea, articulated by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, that states are the laboratories of democracy. What did he mean by that? What was the laboratory of democracy meant to be?

Jacob Grumbach: Louis Brandeis coined the term to suggest that states can do these policy experiments, generating new types of policies to respond to their constituents, and that other states could emulate the successful experiments and reject the failed experiments in the states, and wouldn’t it be a shame if we just had one laboratory, the national government. It’s an argument in favor of having a lot of leeway at the state level—American federalism—and that comes after a long tradition of other arguments in support of American federalism and decentralization of authority in the U.S. Constitution.

Laura: When Brandeis coined that phrase, he was thinking in a particular moment, coming out of the Progressive era, when people were enthusiastic about this idea of experts crafting the best policy and seeing what works and then honing it. Is it just the case that that policy climate doesn’t exist anymore and when it doesn’t exist, the idea of these laboratories doesn’t really make sense?

Jacob: What I’m arguing now is the rise of national parties, where the Democratic and Republican parties are two national teams and the Republican Party has become particularly extreme in opposition to democratic institutions; that this actually has collided with that decentralized system to really threaten American democracy. Those potential virtues of federalism have fallen away, and now states are operating mostly as laboratories against democracy. Right now, because the parties are two national teams, state governments don’t look to other states’ successful policy experiments when they’re made by the other parties. After the financial crisis of 2008, Minnesota and Wisconsin—neighboring states, super similar—Minnesota is doing a relatively decent job getting out of the crisis, rehiring public-sector workers, building back the economy, generating tax revenue. Scott Walker’s Republican Wisconsin is not looking across the Minnesota border and being like, “Oh, we have to emulate this.” Now it’s done within two national party networks, whereas before Brandeis was kind of right that states might look across the country for successful policies. I don’t have statistical evidence of whether that was true back then, but it’s not really true now.

Laura: Right, that was at least the goal back then. When Alex and I were talking about this, we were talking about the idea that politicians are not copying successful policy in terms of policy that delivers the results on those policy objectives, but they’re copying things that work electorally.

Jacob: That’s a nice point, but even electorally, they only copy the electorally politically successful policies from the same party. So that is a big shift.

Alex: To get into more historical context here, your book is in part exploding the cliché or the truism that all politics is local, and it seems to me that you can have it two ways with your thesis: All politics is not local, in the sense that when Scott Walker was in charge of Wisconsin, his eye was on the national scene, on the national Republican Party policy priorities and the national networks. At the same time, politics is local in the sense that the states have an incredible amount of authority over the people residing in them. They have a huge amount of power over the lives of the people in them, which seems like an interesting change.

Jacob: That’s really, really well summarized. We have national parties, national politicians with national ambitions, national interest group networks that are focused on a battle over the direction of the country. But ironically, the effect of that nationalization of politics is that the states actually institutionally become even more important. Now politicians and political activists who are operating in local and state politics are doing so for these national ambitions. This is how you get, for example, the threat of a state legislature giving Electoral College votes to a presidential candidate who doesn’t win the vote in their state for national ambitions. This is how you get even things that seem local, like debates over public school curricula and “critical race theory” and so forth—you might think this is in local school boards, but the places that are having these local politics happen aren’t reacting to some recent local influx of “critical race theory” in your local neighborhood. It’s rather a national ambition, a national line of conflict over culture and the direction of the country.

Alex: You argue there’s a lot of reasons for this nationalization of local politics, but a really important point in your work is who that nationalization benefits and which type of people are most easily able to navigate it. You make this good point that groups that are national in scope but able to operate in this fluid way across state lines have a really important advantage over people who live in a state and thus have ties to the state and are stuck there for professional, personal, or family reasons. Depending on which side of the border you live in, Minnesota or Wisconsin has a great deal of effect on what government you live under, but the groups that take advantage of it are able to seamlessly move from state to state.

Jacob: Another series of optimistic takes about federalism: One is you can vote with your feet. If you don’t like what’s going on in your state, just move to a different state: Your state’s banning abortion, and you don’t like that, move to a state that’s not banning abortion. In a strict political economy, game-theory sense, this is supposed to lead to more efficient governance. But the trouble is that ordinary people can’t just pack up and leave our social networks, our families, our jobs. By contrast, firms, investors, capital can move very quickly now in the globalized age across state lines. This can threaten investors, and large taxpayers and firms can put states in a bidding war and say, “I’ll set up shop in your state if you give me the most tax breaks,” and then states compete against each other to reduce taxes. Ordinary people, social movements, they can’t. “We’re all gonna move away if you don’t expand Medicaid for us”—that is not how that works.

Laura: With the involvement of national networks in state politics, is there a difference in effectiveness between the Republican Party and Democratic Party at doing that?

Jacob: Yeah, it really depends on the issue area there. I came of age in the George W. Bush administration, the early 2000s. This is a classic “If you care about climate change, this is an oil executive president; you’re not going to pass stuff at the national level, so fail globally, act locally.” You did get a ton of coastal states doing new climate regulation, fuel efficiency standards. States on the West Coast raised taxes on the wealthy after the financial crisis. Medicaid expanded after the Affordable Care Act in every blue state and most purple states, disproportionately by Democrats. Liberals and Democrats have been successful in some areas in changing policy. Prior to the Supreme Court ruling that gay marriage was legal, states passed gay marriage laws. On the Republican side, you see it very powerfully in other areas too. Prior to the Dobbs Supreme Court abortion decision, there were huge restrictions on abortion being innovated in conservative states; cutting taxes on the wealthy; deregulating the environment; making it easier to get high-powered guns; and the big, big thing: restricting and dismantling labor unions, especially in the Midwest in the 2010s. In all of these, there’s some symmetry there, support for different movement in those different areas in different directions. But when it comes to democracy itself, the big story is backsliding in the red states.

Laura: Democratic backsliding, for people who aren’t familiar with the term, means erosion of the institutions that support democracy.

Jacob: That’s exactly right. It’s basically how accessible it is to vote; it’s about whether states respond to public opinion, whether they pass policy that’s congruent with the preferences of the majorities that live in their states; it’s about election integrity, postelection audits, and fair vote counting. Probably the most important thing I measure is gerrymandering. I think we understate how big a deal gerrymandering is, but in Wisconsin in 2018, for example, you can often get the case where 35 to 40 percent of voters—those disproportionately rural, whiter, more conservative, wealthier voters in these states—set the majority of the state legislature, so the votes from these more rural constituents count toward the outcomes sometimes multiple times more than an urban constituent. Wisconsin and North Carolina set records, and the influence of a vote from Madison or Milwaukee, the cities, is so much weaker than the nicely gerrymandered exurban districts, and that really makes those conservative voters much more influential over what the state does. That’s been a huge force in democratic backsliding over the past 20 years but especially since 2010.

Alex: That’s a really important point. To get back to some of the myths we’re talking about here, about federalism and about state governments being closer to the democratic ideal because they’re closer to the people: You note that on all of these issues, public opinion in quote-unquote red states, blue states, and purple states can be fairly static on all these issues, but policy outcomes can diverge wildly. You wouldn’t expect that to be the case if states were reflecting the wills of their unique regional electorate; it wouldn’t be the case that we’d have such wildly diverging policy outcomes with static public opinion in all of these different states. It’s actually which states count which votes, right?

Jacob: Exactly. So in some areas, responsiveness to public opinion has been pretty great. On LGBT, or really LGB, rights over those years in the 2000s, it was highly responsive. Marijuana policy, highly responsive, often through ballot initiatives—states first legalized medical marijuana then full recreational marijuana. That really does seem to be popular movement there, and those are two areas where culture and public opinion have really shifted since we were young. Those are responsive policy areas. But on other things, there are huge swings based on when the party that controls the government switches. That you see big swings in policy without swings in public opinion over time within a state like Wisconsin, in that example, suggests that national organizations and groups are really driving the policy agenda rather than the old-school “I’m a highly local state legislature that really is focused on state and local politics in my state.”

Alex: One of the idealistic ideas behind federalism as the Founders intended it was that it was supposed to protect us against some national tyrant. But in the U.S., we’ve got dozens and dozens of local petty tyrants with basically absolute authority. Sheriffs are the best example, or these unrepresentative state legislatures in various states. We have very few protections against these petty tyrants, as opposed to the bogeyman of the one big national one.

Jacob: And they’re not confined to their little tyranny in the states; they regulate elections at all levels. A petty local tyrant is affecting who wins national office in the presidency and the Senate in Congress. That’s a really, really unique and big deal.

Laura: What do you see as the way out of this situation? One way of responding to the power states have is to put more resources into state-level races and try to take over state legislatures. Do you think that makes sense, or are we missing something?

Jacob: When it comes to democracy itself, it’s clear that you need national baseline rules to prevent states from threatening democratic institutions, because states regulate elections from local dogcatcher up to president. Every election is state-administered, same thing with districting. They district for state legislative seats, for the state government, and for the U.S. House in Congress. What the states do really matters, and now they could potentially subvert or essentially steal a presidential election, depending on what the Supreme Court says. All this means national rules are really crucial, but as usual, things pass the U.S. House and then get stuck in the Senate, so clearly you need more political capacity to be able to do policies like this. I think the most underemphasized way to build pro-democracy capacity is the labor movement, but other social movements—you know, when people authentically get interested in issues of democracy itself, like in the civil rights movement, and now there is increasing interest in small-d democracy and institutions, that’s amazing too, and getting involved is crucial. But overall the move has to be toward national policy that limits what states are able to do. Updating policy at the national level is just crucial for any functioning society.

Alex: All right, Jake. Thank you so much for taking the time. That was great.

Jacob: Thanks for having me.

Alex: After the break, we’ll be talking about what’s at stake at the local level in this year’s elections.

Alex: We’re joined now by Aaron Kleinman, the director of research at the States Project, an organization dedicated to improving people’s lives through state legislatures. Aaron, thanks so much for talking to us today.

Aaron Kleinman: Alex and Laura, thanks so much for having me.

Alex: If you pay attention to the national political media, or if you’re a member of the national political media, the midterm elections that we have been hearing a lot about are Congress and then a couple races like John Fetterman versus Dr. Oz, Senate races, congressional races, Joe Biden and the Democratic Party’s approval rate. What are the most important elections that the media hasn’t been talking about and that most people probably haven’t been paying as much attention to?

Aaron: The short answer is state legislative races across the nation. But if you want to just focus in on a few states, I would say the states with the closest chamber of control right now are probably those in Michigan and Arizona. In Michigan, we are two seats away from breaking Republican control of the House and three seats away in the Senate. In Arizona, it’s one seat in each chamber. In both of those states, you could see Democrats feasibly control the chamber for the first time in decades. Those are gonna be the two states that probably, for the casual observer, you would be most interested in following.

Alex: Our other guest talks about the power states have over the people who live in them and hence the importance of state government. Your organization has another argument that I’ve seen you make too, which is while it is obviously important who runs these states electorally, it’s also the case that you—you listeners, an engaged person—can have an outsize effect on political outcomes in these kinds of races compared to the much more national ones.

Aaron: Yeah, that’s correct. Going back to Arizona and Michigan, in 2020, if a few thousand votes had flipped in either state, you would’ve seen Democrats end up controlling those chambers. And if you look at how much was spent on these races, to use Fetterman and Oz as an example, a competitive house race in Michigan is going to cost 3 percent or even less than what John Fetterman and Mehmet Oz spent on their U.S. Senate race. So if you’re Mike Bloomberg, sure, Senate races you can make a huge difference in, but if you are Joe The Politics of Everything listener, you can have a much bigger impact if you want to donate to state legislative campaigns.

Alex: Right. Especially with the amount of money and outside money ballooning the cost of every congressional race, people might not understand that, while I would imagine the dollar amounts have been increasing in these state legislative races, it’s still nowhere near on the same level.

Aaron: Yeah, there’s just this huge resource disparity between federal and state elections. We narrowly missed getting a cap on insulin prices for all patients in the Inflation Reduction Act. Well, in Maine, they were able to cap insulin prices at the state level. You can see at the state legislative level that you can make a huge difference in people’s lives. If you’re a political practitioner or a donor, it costs a fraction, a mere fraction, of what it costs for a federal election.

Laura: I feel like we hear about this a lot, how state legislatures can implement policy that’s very impactful and that really changes the way people are able to live. Why don’t people pay attention to it?

Aaron: There’s been a nationwide trend of polarization and nationalization. There was a study done that showed that there’s a stark decrease in splitting ballots when states got high-speed internet. There are a lot of different potential explanations, whether you’re one of those people who believes that social media puts people into these ideological camps, or maybe a more plausible explanation is that the hollowing out of local news sources harms candidates’ ability to differentiate themselves from the national party.

Alex: I think a really interesting question is how that nationalization has been responded to by the two different sides. Correct me if you think I’m wrong, but it feels to me like the right was a little bit ahead of the curve on this and has been prioritizing these races for a longer amount of time. Is that about right?

Aaron: Yeah, and it’s really decades, because if you want to go back to the early ’70s, that was an era where the post–World War II liberal consensus was still dominant within American politics. At that time, future Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell, who was then the general counsel at the Chamber of Commerce, wrote a quick memorandum on how conservatives could gain back power. There were three major legs to the stool that the conservative movement would eventually sit on. One was building up alternate institutions, media, and academics. That was the impetus for Fox News, for the Heritage Foundation, for the Koch network—that’s the first leg of that stool. The second leg of the stool is the judiciary and installing right-wing judges both at the federal and state levels. That’s how you have the Dobbs decision. The third was state legislatures. They saw very early on that state legislatures were uniquely powerful and uniquely under-resourced, and so they set up groups like ALEC—

Alex: The American Legislative Exchange Council.

Aaron: Yes, right, and you have Club for Growth and a lot of groups set up by Grover Norquist and Paul Weyrich. They were dedicated to making sure that state legislatures, especially in the ’70s,’ 80s, and ’90s, were very anti-tax, anti-regulation. The culmination of the effort really came in 2010, when you had the GOP REDMAP initiative, which for the first time highly professionalized a lot of these state legislative campaigns that used to be run on a bit more of a shoestring, and it led to overwhelming majorities in the Tea Party wave year. Their first order of business became doing ruthless gerrymanders that locked them into power. When Trump got elected in 2016 was when a lot of people woke up and saw, “Wow, one thing that’s been going wrong is we’ve been ignoring state legislatures.” Groups like us, we were founded in 2017 by a former New York state senator. We sprouted up to try to plug that hole.

Alex: One of the questions I want to put to you is why it has taken a while for liberals and left-of-center organizations to catch up. We’ve been talking about the nationalization of local politics, and it has a lot of different ways it manifests itself. What’s interesting is that, from my perspective, the nationalization of politics on the right has meant these well-funded, well-organized national organizations consolidating power in state legislative races. And if you want to talk about the electoral movement, the media being nationalized, local institutions being hollowed out, local newspapers being hollowed out, Sinclair, Fox News, talk radio, all these things, social media having an effect on what local voters do—but it does seem to me that, for the last decade, the nationalization of politics for liberals has not translated the same way. People get excited about these national figures that are challenging hated Republicans, but that energy has not been funneled—except by groups like yours, which is trying to do it—that energy has not been funneled to these smaller races in the same way that the right has managed to channel their money and energy.

Aaron: That’s something I think about a lot. It was the new right that really developed all these organizations that built power at the same time that the new left was developing. If you look at the new left and the organizations on our side that were being founded around that time, they had a view that the next battle was through litigation, the next battle was through very D.C.-centered fights. A big problem with focusing activist energy on litigation is that there’s not a lot of ways that you can build community around it, and especially if you look at the concomitant decline in organized labor. Organized labor has a big stake in who runs state government in a way that a liberal activist does not, and so you lost what you’re supposed to organize around and got basically sucked into this never-ending need for money for litigation—while the right was changing who the judges were and making the prospects for that litigation to succeed less likely.

Alex: Do you see—having been at this for a little while—is there a national left-of-center strategy? Are the big groups beginning to plan what to do about fundamentally gerrymandered states, states that are rejecting democracy, states that are increasingly restricting the franchise, and all these other things?

Aaron: Yeah, absolutely. The Dobbs decision, for people who hadn’t already woken up, that was the wake-up. It was “This is now a fight in 50 state capitals—you better have a strategy to at least minimize the fallout.” For those very, very red states, it’ll probably take a while and a real shift in the culture and the politics to make a huge difference in them. But for now, people have realized that yes, state capitals matter. I have seen a lot of groups that maybe weren’t as focused on states in the past really care a lot about them now. And it’s not just the groups, it’s also the rank and file, the activists. People know just how important these are. If you live in one of these states that has a state legislature that could go to either party or where the supermajority means a lot, going door-to-door and talking to your neighbors is a huge deal, and it’s a thing that you can do that’s free of cost to you. But if you want to give money, visit statesproject.org. We have a lot of different ways for you to get involved.

Alex: Aaron, thank you so much for making the time. It was good talking to you.

Aaron: Thanks so much, Alex.

Laura: The Politics of Everything is co-produced by Talkhouse.

Alex: Emily Cooke is our executive producer.

Laura: Myron Kaplan is our audio editor.

Alex: If you enjoy The Politics of Everything and you want to support us, one thing you can do is go to wherever you listen to the podcast and rate the show. Every rating and review helps.

Laura: Thanks for listening.