For the first time in nearly a year, Democrats have seized momentum. They’re winning special elections they shouldn’t be winning and coming close in ones they really have no right to expect. Legislation is being signed after a long delay, including a $737 billion spending bill and the first piece of gun control legislation in a generation. It’s starting to look more likely that Democrats might ride a backlash to the overturning of Roe v. Wade and concerns about the Republican Party’s authoritarian drift to avoid a historic midterm beatdown. Even Joe Biden’s anemic poll numbers have inched upward in recent weeks. After months of inertia, Democrats are finally getting some things done.

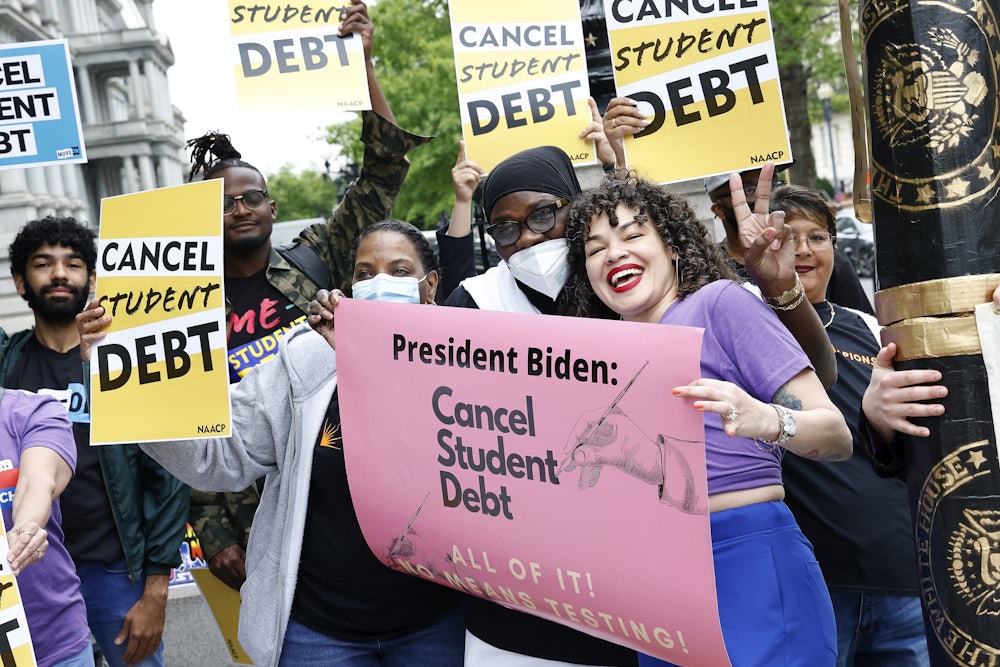

Naturally, some in the party’s “center” have begun to ask if maybe it was doing too much. Here’s what’s pushed them over the edge: The Biden administration’s decision to cancel up to $10,000 of student debt for millions of borrowers making less than $125,000 a year—and more for Pell Grant recipients—has been hotly debated for months. The means-tested plan released by the administration has modest top lines compared to many plans—in typical Biden-administration fashion, the level of generosity on that score seems calibrated to bring complaints from those who think it’s done too much and those who think it did too little. But there are interesting details in the bill’s fine print that will considerably expand debt relief. And the White House projects that it will aid 43 million borrowers while wiping out the debt of more than 20 million. Not too shabby.

But for some Democrats, Biden’s debt relief plan is proving to be enormously controversial. For progressives, who rightly cite the enormous, multitrillion-dollar debt load carried by Americans, often for several decades, the plan offers a mere soupçon of reform for a defective, extortionate, and corrupt system. For centrists, the big giveaways are an affront to frugality and the storied American tradition of nearly everybody being deeply in debt for no good reason.

The latter group seems to have the loudest complaints at the moment. Nevada Representative Catherine Cortez Masto dinged the plan because it didn’t “address the root problems that make college unaffordable,” adding that “we should be focusing on passing my legislation to expand Pell Grants for lower-income students, target loan forgiveness to those in need, and actually make college more affordable for working families.” Colorado Senator Michael Bennet concurred, while also critiquing the plan for not being “targeted” enough or paid for—presumably via spending cuts. New Hampshire Representative Chris Pappas, meanwhile, criticized the administration for sidestepping Congress: “Any plan to address student debt should go through the legislative process, and it should be more targeted and paid for so it doesn’t add to the deficit.”

This is, to a certain extent, politics: Student loan forgiveness is a contentious issue, and if you’re a Democrat facing a tough election in a swing district, you want to be on the right side of it. But it wasn’t just centrist lawmakers with their eyes crossed in the cross tabs yammering about Biden’s plan. Much of the criticism came from familiar and expected places: Economists Jason Furman and Larry Summers fretted about its potential inflationary consequences, with Furman tweeting that it was foolhardy: “Pouring roughly half trillion dollars of gasoline on the inflationary fire that is already burning is reckless.” Third Way, the think tank that is the Eeyore of Democratic politics, meanwhile, noted that the plan will certainly face legal hurdles and may go down in flames.

“Advocates and policymakers who pushed to take this unprecedented step are responsible for also communicating to borrowers that there is a strong chance it will never come to fruition,” the think tank’s social policy director, Lanae Erickson, told The Washington Post. “Given that the application may not be available until the end of the year, the strong likelihood is that courts will enjoin this action before it gets started—leaving borrowers in limbo.” Leave it to Third Way to be the organization cheering for a predatory loan servicer to step forward and obtain relief from Samuel Alito and his merry band of right-wing culture warriors.

But many of these criticisms aren’t entirely unfair. The inflationary consequences of Biden’s move are unknown. “Economists say that a tailored debt cancellation plan is unlikely to exacerbate short-term inflationary pressures, but could add to them in the long term, especially if universities continue to raise tuition because students might expect their loans to eventually be canceled,” The Wall Street Journal’s Andrew Restuccia and Gabriel Rubin reported. But Joseph Stiglitz argues in The Atlantic that Biden’s plan will help reduce inflation: “Whatever your view of student-debt cancellation, the inflation argument is a red herring and should not influence policy,” he writes, adding, “A closer look at the student-debt-cancellation program suggests that the new student-loan policy may even reduce inflation; at most, its inflationary impact will be minuscule, and the long-term benefits to the economy are likely to be significant.”

But the open question leaves room for political risk. Should inflation revert back to rising at the levels it was earlier in the year, this decision will undoubtedly be blamed by both centrists and Republicans. A theoretical legal challenge would require a plaintiff, and it’s not certain that any with the standing to sue will make the attempt, but the current Supreme Court, tilted as it is somewhere to the right of The Big Lebowski’s Walter Sobchak, has shown a propensity to throw out the rules when that majority wants to do so. And congressional centrists also have at least two good points. The overarching problems that have led to the student debt crisis are structural. And Congress is the best place to solve those problems.

Here’s the puzzlement, though. Despite the broad acknowledgment of these deep structural problems, there are no plausible policies being put forward to address this crisis—and certainly not any that are poised to pass a divided Congress and solve the student debt crisis. The centrist critics of the plan pivot from arguments that Biden’s debt relief is both too ambitious (that is, it should be further targeted) and not ambitious enough (that is, it doesn’t do enough to fix a thoroughly rotten system). But these fixes would almost certainly require both a heavy-duty rethinking of higher education in America and the wiping out of massive amounts of debt. While these critics seem to have endless energy to complain about these larger problems, they demonstrate no stomach for actually fixing them. There is, more importantly, simply no way that Democrats would be able to pass anything, given their razor-thin majorities. But this is where the centrists take their convenient refuge. Their caviling, ultimately, is not an authentic call for reform—it is an implicit endorsement of a status quo that burdens ordinary Americans with economic inequality.

It will continue to be unless centrist Democrats can actually put a policy together that addresses the problems that have led to this decades-long crisis. But as I’ve noted before, this caucus of constant carping has nary an idea to its name—and there’s nothing to suggest these critics are going to change anytime soon. Biden should probably note how they are responding to a plan that’s much more moderate than debt-forgiveness advocates would have demanded and point out how often they weaponize a perfect they never intend to try to achieve, as the enemy of the good.