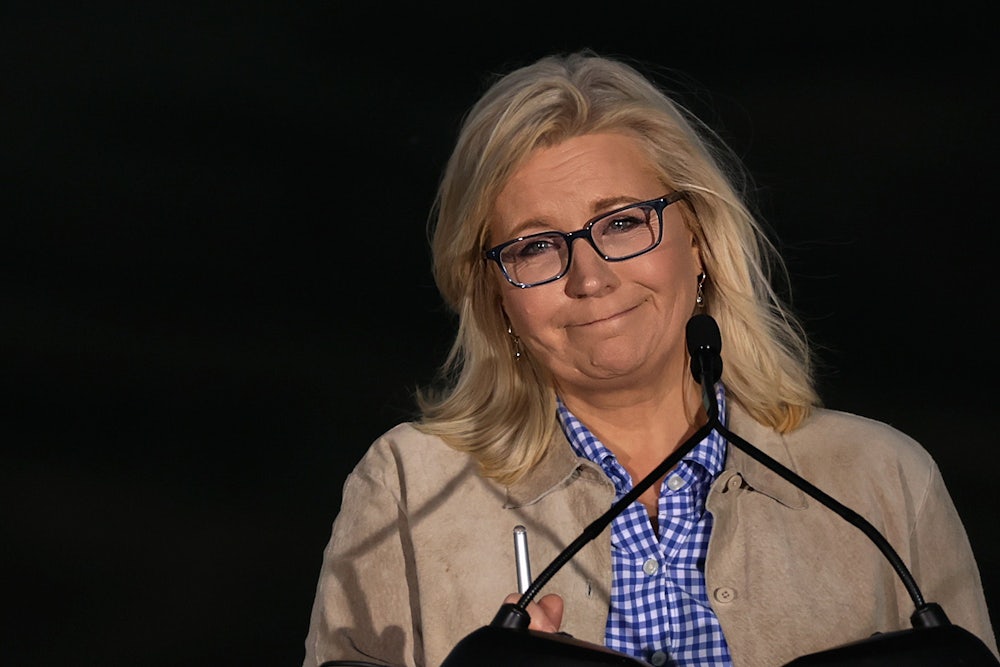

Liz Cheney’s political career is over—and that’s why she’s almost certainly running for president.

The Wyoming Republican who served as her state’s at-large member of Congress for two terms was walloped in her primary against Harriet Hageman last week, losing by more than 30 points. This is not exactly an ideal launchpad for a presidential campaign. But Cheney—political royalty if you count “being the daughter of one of the most destructive figures of the last half-century” as a dynastic point—is not your typical presidential candidate. And she’s not going to run for president with the idea that she stands a chance at winning. Hers is a kind of suicide mission. Cheney will be defeated, earning nary a delegate in all likelihood. But her plan is to try to wrest control of the Republican Party, at long last, away from Donald Trump.

As desperate as Cheney’s mission may seem, she is arguably better positioned than any other Republican to make an attempt. No one in their right mind would mistake her for a liberal—she’s Dick Cheney’s daughter after all, and despite really being from northern Virginia, she spent two terms in Congress representing one of America’s reddest states. She marched behind Donald Trump and supported him during his first impeachment, only really breaking from him after he tried to foment a coup.

Since then, she can and has made the case that Trump—and other autocratic-minded Republicans thought to be entering the 2024 presidential race, such as Florida Governor Ron DeSantis—have broken from the party’s core values and represent a dangerous authoritarian turn. Her work, moreover, as a member of the House committee investigating January 6 has placed her in an ideal position to make that case and take it to Republican voters who rarely hear it.

Cheney’s scheme is a tantalizing idea. Perhaps some regal figure in the GOP’s ancient constellation could map a path back to something that resembled a normal Republican Party. What makes it implausible is that Republican voters largely believe that Joe Biden stole the election; they have voted for figures who also believe this—or at least claim to—across the country. And they’re not going to listen to the figure they only just excommunicated from their ranks.

It’s not impossible to see why Cheney believes she has a ghost of a chance to supplant Trump. The GOP primary will undoubtedly focus heavily on the former president’s insane conspiracy theories about how the 2020 election was stolen from him—and the extent to which other Republicans vying for the nomination agree with them. The affirmative case for a Cheney presidential run is that she is well positioned to remind GOP voters that these are lies, that Donald Trump is a lunatic, and that the party is better off without him—or his protégés in waiting.

Perhaps she’ll get lucky and Republican voters, who are rarely subjected to ideas that deviate from the party line, will find Cheney’s argument persuasive. “Given how little GOP primary voters are confronted with counterprogramming on Trump—both by virtue of our siloed conservative media and a lack of willingness by DeSantis, Pence, et. al., to truly go after Trump—Cheney might view that as a worthy path if she truly only aims to stop Trump,” wrote The Washington Post’s Aaron Blake last week.

But plenty of Republicans have taken a run at Trump. The National Review made its “Against Trump” case in the early days of his career as a presidential candidate. It’s since taken a circuitous journey in the direction of capitulation, first occupying a trendy anti-anti-Trump position before settling into a somewhat bumptious pro-Trump-lite stance. Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz both briefly argued that he was unfit for office (among other things) during the 2016 election; both have since bent the knee.

Mitt Romney has stayed on Trump’s bad side and remained in office, a relative rarity among electeds who’ve given Trump consistent static. Several Republicans who have made anti-Trump arguments their mainstay have either been run out of town on a rail or took their own leave after recognizing that their fortunes had fallen by the wayside. Remember Jeff Flake? You probably don’t. He wrote a whole book about how Trump was terrible and how the GOP must embrace conservatism again. You probably don’t remember it, but that’s OK: Nobody cared.

Cheney, one supposes, can at least go for broke. She can be more aggressive than these other Republicans because her political future has been written in advance: As long as Donald Trump or his acolytes man the commanding heights of the GOP, she has no future in it. So there’s no reason for her to pull punches. She could be a more forceful advocate for anti-Trumpism than, say, milquetoasts such as Bob Corker, or former sycophants like Chris Christie. But while Republican voters likely harbor little affection for these Republican Party dissidents, they absolutely despise Cheney. As of last week, 17 percent of Republicans had a favorable view of her, per a YouGov poll. That is hardly a perch from which to launch a successful campaign for anything, let alone bringing down a figure Republican voters adore. Her larger case may also be doomed: Only 25 percent of independents like Cheney, suggesting not only that the audience for her message is small but that it could backfire. (A shocking 60 percent of Democrats approve of Cheney, however—meaning that an independent presidential campaign could end up getting Trump elected to a second term.)

Perhaps the biggest problem with Cheney’s candidacy is that the GOP primary is not going to be monomaniacally focused on the fact that Donald Trump thinks that Hugo Chavez’s ghost stole the 2020 election. How will Cheney make her case when the presidential race turns to matters like foreign policy or taxes or health care or the culture war? Donald Trump was able to wrest control of Republican stalwarts like Cheney and her father in part because lots of people hated their ideas. In particular, they had soured on long, costly, losing military interventions and the status quo on trade.

It’s not that Trump ever capably offered an alternative: He was as bellicose as any recent president when it came to military intervention and abandoned his populist pretensions in favor of Republican orthodoxy in most areas of economic policy almost immediately after assuming office. But Cheney hasn’t articulated an actual alternative political vision for the Republican Party; presumably she is a stalking horse for a return to the early-2000s status quo—which, of course, gave us Donald Trump. Cheney will have to spend most of her time on the debate stage—if the GOP even allows her to appear there—talking about these matters.

This points to a larger problem for the anti-Trump right: There still isn’t a prescriptive vision for what conservatism looks like post-Trump; many “anti-Trump” Republicans are only really displeased with the aesthetics of Trumpism, not the ideas themselves. That shouldn’t be surprising, given that the hostility to democracy and multiculturalism was always a feature of the American right. But seven years after Trump launched his first presidential bid, the perpetually entitled old guard who lost their party are still scrambling to solve the problem. And the solution is always the same: Trust us, we’re the experts, just put us in charge again.