In Fleet Street, August used to be called “the silly season.” Families were on holiday, Parliament was in recess, political leaders were away, and the papers carried frivolous stories, because “nothing happens in August.”

In fact, of course, many things have happened in August. Over the first half of the last century, two appalling wars broke out. On August 3, 1914, Germany declared war on France and invaded Belgium, ensuring British entry into the war, and on August 23, 1939, the Nazi-Soviet pact cleared the way for Germany to invade Poland nine days later, ensuring British and French entry into a war that ended six years later when Japan surrendered—on August 14, 1945.

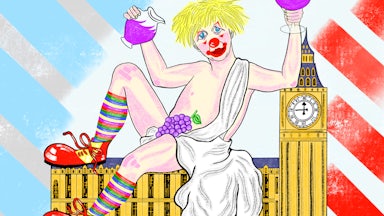

If this August in England hasn’t been as dramatic as that, it has seen something unprecedented, although in a way silly enough: a protracted, nasty, vulgar, and at times, simply grotesque public contest for the position of leader of the Conservative Party, and thus prime minister of the United Kingdom. All this follows the bloodless political assassination of Boris Johnson, and it demonstrates his calamitous legacy to party and country. In The New York Times, Michelle Goldberg has congratulated the British and our system of parliamentary government on the expeditious way an unworthy head of government can be removed, something Americans can only dream of. But if we can claim to set an example in getting rid of one leader, we are now giving an object lesson in how not to find a new one.

Under the weird hybrid system the Conservatives have saddled themselves with, Tory Members of Parliament can stand for the leadership if enough fellow MPs endorse them, and then progressive ballots among the MPs reduce the number to two, one of whom is then chosen by party members. That now means, in practice, weeks of television debates and public hustings, with the candidates making cheaper and cheaper attacks on one another and more and more expensive promises about tax cuts and spending. (Yes, that’s right, lower taxes and higher spending don’t seem logically compatible, but logic has very little to do with this business.)

We have now reached the point where the contenders have been winnowed to two. Of the pair, Rishi Sunak might seem the grown-up choice, a former Chancellor of the Exchequer with at least some grasp of economics. His opponent, Liz Truss, has made much of the fact that she went to a state school whereas he went to Winchester, the oldest of what the English quaintly call public schools, meaning elite boarding schools. He replies, reasonably enough, that he’s proud of his parents, who arrived as penniless immigrants from the Punjab and did well enough to give him a good education, and that anyway he went to Winchester with a scholarship won on merit, just as the two of them both won places at Oxford. And by the way, whoever wins will mean that, out of 16 prime ministers in the past 80 years, 12 went to Oxford. We Oxonians might perhaps take pride in that, but I find this near-monopoly a little worrying.

More of a problem is Sunak’s wealth, acquired during a career at Goldman Sachs and in hedge funds, and his wife’s far greater fortune. She comes from one of the richest families in India, and was for years a “non-dom,” the highly dubious status by which someone who lives in England most of the time can be technically non-domiciled and avoid income tax. Besides that, the saying goes that he who wields the assassin’s knife never gets to wear the crown. That wasn’t true of Margaret Thatcher when she challenged Edward Heath for the Tory leadership in 1975, but it was true of Michael Heseltine when he challenged Thatcher in 1990, bringing her down but failing to succeed her. Sunak wielded the knife when, having at last had enough of Johnson’s incompetence and bumbling mendacity, he resigned as Chancellor and precipitated the cascade of resignations that forced Johnson to quit. But since most Tory party members regret the departure of Johnson and even want him back (which tells you all you need to know about those members), that’s held against Sunak.

Our departing prime minster set new standards in tawdry demagoguery, shouting about a Brexit in which he had never seriously believed. But while pandering to the mob sometimes means nativist bigotry, as seen today from Hungary to Arizona, it doesn’t have to be so. The Tories’ latest incarnation shows that. Americans sometimes talk of English racism, antisemitism, misogyny, and whatnot, to which I shyly point out that in 1868 we had a prime minister called Disraeli, and in 1979 we had one called Margaret. Fifty years ago—a hundred years after Benjamin Disraeli had reached the top of the greasy pole, as he called it—Barry Goldwater looked back ruefully on his crushing defeat in the 1964 presidential election, and said that he didn’t think the American people were ready for a president with a Jewish name. Whatever else is said about Goldwater, he might have been right there.

And whatever else is said about the Tories today, with all their populist Europhobia and intermittent jingoism, they are visibly not a white nationalist party. They were once the party that stood for the British Empire, and that arch-imperialist (and racist) Sir Winston Churchill said at the last Cabinet meeting he presided over before he resigned as prime minister in 1955 that the Tories should fight the next election on the slogan “Keep England white.” Not only has it not been kept white, but the former Empire has taken a kind of revenge. Bruno Maçães is a Portuguese politician turned prolific pundit. He listed the latest three British politicians who have held the office of Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sajid Javid, Rishi Sunak, and Nadhim Zahawi, and said that there is no other European country where three men with such names could have been successive finance ministers. Of the original eight MPs who stood in this contest before the numbers were whittled down to two, only two were male and white. Nor can the Tories be called sexist. As I write, Liz Truss is the hot favorite to win, which would make her the third woman prime minister we’ve had, all of them Tories. As you may have noticed, you Americans have yet to elect a woman president.

But still, having either two X chromosomes or a brown skin can be no guarantee in itself of political wisdom, and what we’ve seen this August has been a lowering and unseemly affair, a contest that reflects badly on the Conservatives and the country. How did the party, and the rest of us, get into this predicament anyway? From the start, Labour, as a democratic party, elected its leaders, which is to say that they were elected by Labour MPs. That was until the Labour defeat by Thatcher and the Tories in 1979, the rise of a quasi-Trotskyist left in the Labour Party, and the temporary ascendancy of Tony Benn, who failed to become leader but succeeded in changing the way the leader was chosen, now by a bizarre “electoral college” comprising MPs, trade unions, and rank-and-file party members.

Far from learning from this horrid example, the Tories emulated it. Their leaders had traditionally taken over without any formal electoral procedure. That didn’t matter when there was an acknowledged crown prince, as when Neville Chamberlain succeeded Stanley Baldwin in 1937 or Anthony Eden succeeded Churchill in 1955 (not that either Chamberlain’s or Eden’s premiership ended happily). But when Eden resigned in 1957, Harold Macmillan sinuously and unscrupulously grasped the succession, thwarting R.A. Butler, who would have made a much better prime minister, and in 1963, Macmillan even more unscrupulously jockeyed Lord Home into place as his successor, again rather than Butler.

This led to the famous polemic in The Spectator in January in 1964 by Iain Macleod, a senior Tory who had declined to serve under Sir Alec Douglas-Home, as Home had become known after renouncing his peerage. Macleod’s polemic caused great anger at the time and his account has been questioned since, but when he wrote that “the result of the methods used was contradiction and misrepresentation. I do not think it is a precedent which will be followed,” he was quite right. Douglas-Home led the Tories to a quite narrow defeat in the 1964 election and resigned the party leadership the following year, by which time the Tories had decided that their leader should be elected by the party’s MPs. That was how Edward Heath was chosen in 1965, how Margaret Thatcher deposed him in 1975, and in turn was deposed in 1990 (when she won the vote against Michael Heseltine, her challenger, but his support was so numerous that she gave up).

After they were routed by Labour under Tony Blair in 1997, the Tories followed the foolish Labour example, in their case with this hybrid system of MPs eliminating all but two names for the party members to choose from. Since then, something has gone badly wrong with the Conservative Party. Salisbury led the Tories for 17 years, Baldwin for 12 years, and Churchill and Thatcher for 15 years each. In the 22 years after Thatcher ousted Heath, the leadership changed just once; in the 25 years since then, it has changed eight times, including this latest case, and terms of office have become far shorter. Duncan Smith was leader for two years, Theresa May for just over three years, as was Johnson.

And something will have gone more gravely wrong if Truss becomes prime minister. She comes from a left-wing family and in younger days was herself an ardent Liberal Democrat, when she advocated the abolition of the monarchy (that will give the Queen something to talk about when they meet). She was also a Remainer in the referendum on the European Union but now promises a harder-than-ever Brexit to ingratiate herself with the party members. They are fewer than 200,000 in number and, unlike the MPs and contenders, almost all white, mostly male, middle-aged or older, and well to the right of the nation—or even most Conservative voters—as whole.

MPs were the right constituency to choose a leader because they themselves have been elected by the populace. A party member is chosen by no one but herself—or in this Tory case, much more often himself—by applying to join and paying modest dues. These are the people, rather than the nation, to whom Truss is appealing with her tax-cutting claptrap. We’re all entitled to change our minds and sometimes we should, but Truss’s evolution suggests less an open mind than a keen eye for the main chance.

In the meantime, Johnson stalks resentfully away from Downing Street. His wretched farewell speech in the Commons ended, “Hasta la vista, baby,” which sounded like a threat. When Baldwin departed, he promised that he wouldn’t “spit on the deck or speak to the man at the wheel.” Johnson looks as if he’s prepared to spit in his successor’s face.

What does he leave behind? On Thursday August 4, 108 years since Great Britain went to war with Germany, there was another feeble and fruitless debate between Sunak and Truss, in which she yet again promised tax cuts, which she claims against all evidence will combat inflation. But whatever she said was entirely overshadowed by the apocalyptic warning that day from Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England. As he announced another rise in interest rates, he warned that the country was heading for inflation at 13 percent, a protracted recession, and the worst squeeze on living standards in 60 years. We may have been listening to a silly contest fit for the silly season, but our predicament is all too serious. “Britain slides into crisis” was the front-page headline in last Friday’s Times. The Tories have been in power for 12 years. On whom would Rishi Sunak, Liz Truss, or Boris Johnson care to place the blame for our plight?