If the recent hearings by the House Select committee investigating the January 6 attack on the Capitol have taught viewers anything, it is that the foundations of American democracy are more precarious than anyone previously believed.

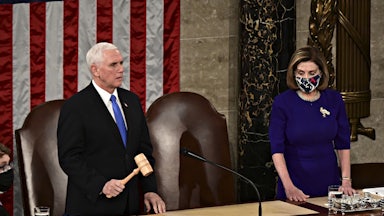

Setting aside the insurrection spurred by an outgoing president, more than 100 House and Senate Republicans voted to overturn the election results in several states, despite the failure of dozens of lawsuits brought by President Donald Trump’s campaign. But a more worrisome scenario remains in the form of the road that was—ultimately—not taken by the vice president and some state elections officials. When it mattered, then-Vice President Mike Pence opted to not heed the urgings of Trump lawyer John Eastman to attempt to unilaterally overturn the election results himself.

But thanks to the vagueness of the Electoral Count Act, the statute which outlines the process for counting Electoral College votes, it’s not inconceivable that a future vice president could try to subvert the election, or that a president unwilling to step down could be aided and abetted by partisan state officials to carry out a similar plot.

In an effort to avert that possibility, a bipartisan group of senators worked for months to craft legislation that would streamline and clarify the process. Last week, the fruits of their labor were finally revealed: The Electoral Count Reform Act, or ECRA, spearheaded by GOP Senator Susan Collins and Democratic Senator Joe Manchin, and sponsored by eight Democrats and nine Republicans.

“It took the violent breach of the Capitol on January 6 to really shine a spotlight on how urgent the need for reform was,” Collins said in her opening statement before the Senate Rules Committee in a hearing on the legislation on Wednesday. The hearing was the congressional equivalent of a lovefest, with senators complimenting and thanking each other for their bipartisan efforts.

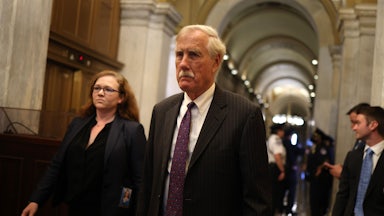

“It is an example of how this place can and should work. It involves, I know, compromise, and a great deal of discussion, and a great deal of research,” said Senator Angus King, who had previously worked on separate legislation to reform the Electoral Count Act. GOP Senator Roy Blunt, the ranking member of the committee, said that Congress had the “opportunity” to “get this bill passed this year”—and indeed, it seems to have sufficient support to overcome a filibuster. Could the Senate actually pass legislation to address one of the biggest issues facing our democracy?

In an era of hyper-polarized politics, compromise can be seen as remarkable. Experts, many of whom have been warning about the imprecise nature of the Electoral Count Act for years, largely praised the new bill. “I think it’s a monumental achievement,” said Matthew Seligman, a fellow at Stanford Law School who has written extensively on the Electoral Count Act. “If you had told me on January 7, 2021, that we would have legislation like this with the level of bipartisan support that it has.… I would have been overjoyed.”

The bill aims to prevent a slate of false electors—that is, electors who do not represent the candidate who won the popular vote—from being certified. One of the Trump campaign’s strategies in the wake of the 2020 election was to attempt to promote false electors in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, New Mexico, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, all states that Biden won. (The New York Times reported this week that two Arizona Republicans worried that participating in a plan to create a slate of fake electors could “appear treasonous.”)

The bill would require states to appoint electors based on state laws that existed prior to Election Day—meaning that a disgruntled state legislature could not appoint a slate of electors counter to the popular vote. It would also prevent state legislatures from declaring a “failed” election in order to appoint their own slate. The bill declares that a governor has the “conclusive” authority to certify a slate of electors; but it also allows for a candidate to trigger a speedy judicial review by a federal court, and requires Congress to count electors approved by the court.

For the actual counting of electoral votes on January 6, two weeks before the inauguration, the bill clarifies that the vice president has only a ministerial oversight role. It also raises the threshold for objecting to a state’s electoral results from a single member of both chambers to one-fifth of members of both the House and the Senate, and limits the kinds of objections that members of Congress can raise.

The Electoral Count Reform Act has not been met with universal support. Democratic lawyer Marc Elias worried that the bill would allow governors to certify any slate of electors they want, regardless of the popular vote. But defenders of the bill say that the stipulation that the slate of electors be consistent with state election law prior to Election Day, as well as the expedited judicial review, would prevent a rogue governor from certifying the wrong slate.

“The courts are going to assess, if necessary, whether the governor in fact complied with the law. And if the courts determine that the governor did not comply with the law, the court’s ultimate determination and any revised certification that the court orders replaces and supersedes that initial certification,” said Adav Noti, the vice president and legal director for the Campaign Legal Center, explained to reporters on Wednesday. A fact sheet for the bill specifies that “Congress to defer to slates of electors submitted by a state’s executive pursuant to the judgments of state or federal courts.”

Moreover, the bill sets a hard deadline for electors to be certified: six days before the counting of electoral votes. In his statement before the Senate Rules Committee on Wednesday, Manchin said that the bipartisan group was “open to some technical fixes to address timing concerns,” such as exempting the three-judge panel conducting the expedited review from being subject to a five-day notice requirement, but said that “we stand by this provision as a way to quickly and efficiently determine a single lawful slate of electors.”

Norm Eisen, a good government advocate, also worried that the bill’s lack of definition for what amounts to a “failed” election could result in states declaring their own “catastrophic events.” But Bob Bauer and Jack Goldsmith countered in Lawfare that, “The ECRA is not the place to catalog what may be catastrophic events (e.g., a cyberattack, widespread power outages), which instead are properly left to state determination.”

Further, the bill limits what a state can do even in the case of a catastrophic event: state legislatures could only extend or alter the voting period. “It takes off the table the opportunities for a state legislature to step in and say, ‘We’re just going to decide who won the election,’” said Noti. “Even if you think that could be made more specific, the only result is that the state is allowed to extend the voting period.”

With confidence in the judicial branch at historic lows, there is also the question of whether a panel of federal judges—subject to appeal to the Supreme Court—would always rule in favor of the slate of electors that reflects the popular vote. But Seligman argued that it was better to trust the courts than, say, a hypothetical Governor Doug Mastriano, who has promoted conspiracy theories about the 2020 election and was outside the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

“This is a relative risk assessment. So, you might think that there’s a risk that politically motivated judges will make a decision to put in their favorite candidate rather than the one that legitimately won the election. And my point is that the only alternative is putting that final decision in the hands of politicians,” Seligman said. He noted that the Supreme Court dismissed a lawsuit contesting 2020 election results.

Even supporters of the bill are quick to note that it does not address all of the concerns about threats to democracy. In a separate hearing on Wednesday by the Senate Judiciary Committee on threats against election officials, Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson said she was “grateful” for the proposed reforms to the Electoral Count Act, but argued “that is not enough.” “Imposing stronger penalties on those who would threaten or harm anyone involved in election administration is an important step,” Benson said. A second bill introduced in concert with the Electoral Count Reform Act last month would increase penalties for threatening election officials and tampering with ballots and voting systems, but it is co-sponsored by only five Republicans.

Democrats have also failed to pass significant voting rights legislation, in large part due to Manchin’s opposition to ending the filibuster in order to do so. In her prepared statement before the Rules Committee on Wednesday, Janai Nelson, the president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, said that “this Congress must also address voting discrimination to fulfill its obligation to respond to the Insurrection and rescue our democracy from present peril.” There are also the pending recommendations from the January 6 Committee on the Electoral Count Act, and how to reform it.

Despite any shortcomings, supporters of the bill believe that Congress must act on it quickly. Democrats are widely expected to lose one or both chambers of Congress in the midterms, and it is unclear whether a Republican House or Senate—and particularly one with a higher percentage of 2020 election deniers—would be inclined to pass such a bill. But even without that complicating factor, it is difficult for Congress to pass significant legislation in the run-up to a presidential election.

“It is absolutely true that the risks that are posed by political manipulation of the electoral count are symmetrical. Democrats could do this too,” Seligman said. “But in the last five years, the Republican Party is the one that has demonstrated that it is willing to do this. And so, I think given that obvious fact, the next few months are our one and only chance to pass this legislation, and this legislation is our one and only chance to protect the electoral count in 2024 and beyond from political manipulation.”