Two recent Supreme Court decisions have sounded, to many observers, like a death knell for the separation of church and state. The six conservative justices have torn a hole in the wall of separation, or taken a “sledgehammer to the bedrock” of the principle that the state must remain neutral and impartial toward religion. These fears may be well justified. But if church-state separation is worth protecting, it is not because of what it is, but rather what it allows us to create: an equitable democracy where we all share in public goods and institutions.

In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the court decided that the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment protected Joseph Kennedy, a coach employed by the school district in Bremerton, Washington, while he prayed on the field following football games. The dissenting opinion saw a violation of the Establishment Clause, focusing on how the coach invited others to pray with him on the 50-yard line—with students and the public watching. In Carson v. Makin, the court ruled that tax dollars were allowed to fund vouchers for sectarian schools in Maine, because the state’s requirement that funds be given only to “nonsectarian” schools discriminated against religious schools by violating the free exercise of potential students and taxpaying parents.

Many observers have considered what Carson and Kennedy mean for religious freedom, the separation of church and state, and the continued rise of Christian nationalism. After the Carson decision, The New York Times charted the rise of a “pro-religion court,” declaring that the court is the most “pro-religion it’s been since at least the 1950s.” A Hindu student who feels the coercion that Justice Sonia Sotomayor mentions in her Kennedy dissent—the pressure to pray with their evangelical coach—would likely disagree. To take another example, some Jews have argued that a lack of access to abortion violates their religious freedom.

What does it mean to be “pro-religion”? And whose religion? These questions are worth asking. But if we think they are the only questions, and if we consider these cases as primarily about religion, we might miss how religious freedom is related to other freedoms. Yes, this is all about religion, but it’s about bigger matters as well.

We will have more clarity—analytical, political, even moral—if we think less about these cases as pro- or anti-religion and more about how they are pro- or anti-public or democratic. The problem with these decisions is not just that they undermine church-state separation. That framework has little historical consistency or essential meaning. It’s hard to defend a moving target. But at its best, separationism is a principle that allows for a fairer, more democratic society. That has not always borne out. Even when the wall of separation was higher and sounder, religion in American law was still “church-shaped,” and in practice our public institutions have tended to favor white Protestants. The court’s recent efforts to chip away at separation should be seen instead as an essential part of a much larger project: To undermine church-state separation is to diminish the strength of public institutions, most notably public schools.

One interpretation of Kennedy and Carson is that the court privileged free exercise, the freedom of individual believers, over disestablishment. Or, as legal scholar Micah Schwartzman put it, re-upping his pithy tweet from 2020, “So … the Establishment Clause violates the Free Exercise Clause. That’s the tweet?” Sotomayor sees it similarly. In her Kennedy dissent, she argued that the court’s decision—siding with the coach—“elevates one individual’s interest in personal religious exercise, in the exact time and place of that individual’s choosing, over society’s interest in protecting the separation between church and state, eroding the protection for religious liberty for all.” Again, we need to think more about why an individual’s interest trumped the interests of broader society. Free exercise superseding disestablishment, one clause canceling out the other, is but one instance of many where courts have recognized certain individual rights and privileges while stripping down public institutions and encouraging private interest to trample any robust notion of the public good.

Public schools hold a prominent place in the history of establishment clause jurisprudence, but they hold less and less of a place in American society and in the lives of students. According to a recent study, only 68 percent of Gen Z students are enrolled in a traditional public school (and 13 percent are in public charter schools). This represents a decline in overall public school enrollment, and a shift from public to charter schools, marking education’s latecomer status to the privatization of public goods. (Not everyone thinks this is a bad thing.) It is worth noting that Betsy DeVos, President Trump’s secretary of education and a longtime champion of school privatization and opponent of public schools, wrote an amicus brief in support of Coach Kennedy.

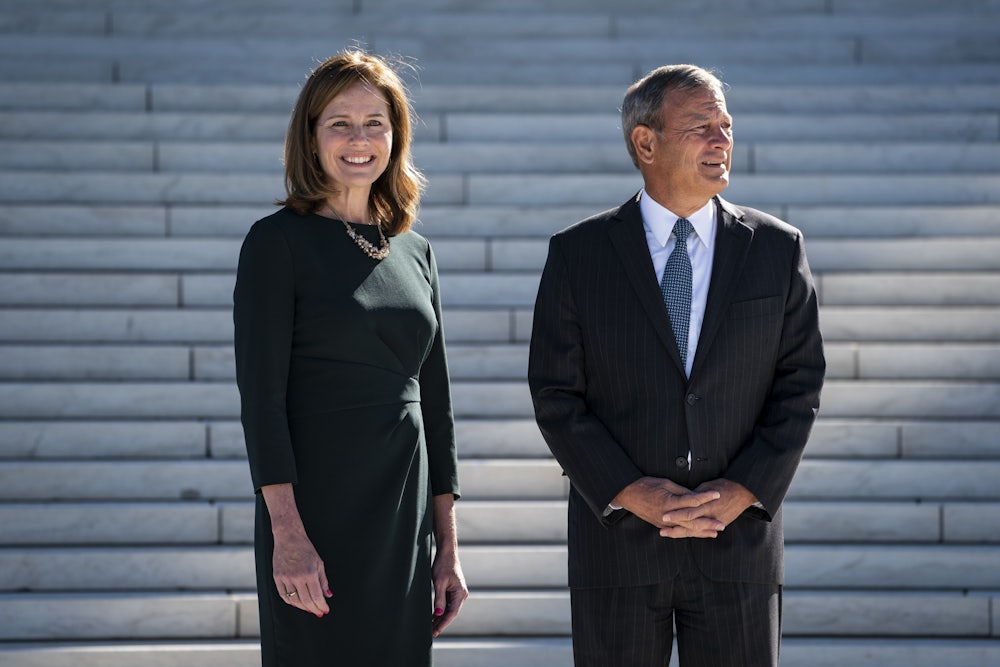

Ideally, public schools serve the public good. In theory, there are fewer barriers to enter public schools than private schools. As Chief Justice John Roberts writes in his opinion for Carson: “private schools are different by definition because they do not have to accept all students. Public schools generally do.” A history of segregation, redlining, and income disparity has meant that all public schools are not equal. Predominantly white schools are consistently better funded than schools with predominantly students of color. Moreover, Black students face arrests at a higher rate than white students, which not only criminalizes Black students but is sure to make learning more difficult.

Public schools have never fully lived up to their potential, because of white parents’ unwillingness to compromise on their definition of “good education,” conflicts between public and private goods of education, and the white Protestantism baked into educational reformers’ understandings of an American citizen. While nineteenth-century common schools (the predecessors to today’s public schools) reputedly established a liberating separation of church and state, they did not renounce religion. Instead, they universalized Protestant ideals of the common good, which collapsed religious and racial distinctiveness into the white, male, Protestant as the ideal citizen.

Given that these harms have primarily negatively affected students of color, critiques of capitalist and culturally siloed pedagogy are vital. Yet critiques of these public school practices are not inherently anti–public schools. It is true that public schools have always been spaces for a discriminatory moral formation. But the ideal—a genuinely inclusive education, especially in settings that welcome everyone—should serve the common good and further democracy.

We have seen that school choice promotes discrimination through segregation academies. The named plaintiff in 1971’s Lemon v. Kurtzman, Alton Lemon (whose own Blackness and role in the NAACP is often overlooked), said, “If a lot of public funds are siphoned off, Blacks and minorities are going to suffer.’’ Kennedy has now officially overruled the Lemon Test resulting from that case—a test that may have been imperfect because of its definition of religion, but that emerged from a named plaintiff concerned with public resources for those with the least access to them. Our concern with funds to Bangor Christian and Temple Academy is not that the schools are Christian, but that, as Justice Breyer notes in his dissent, they discriminate against LGBTQ people. Discrimination puts LGBTQ people at higher risk for mental and other health issues, harassment, and assault.

If Kennedy and Carson are examples of free exercise trumping disestablishment, this is due in part to the dramatic shift in free exercise law over the past two decades. Backed by conservative Christian legal organizations and their use of the expansive category “sincerely held religious belief,” certain believers have been enabled to flout antidiscrimination laws, vaccine mandates, and other government actions that might burden their conscience. From the opening pages of the Kennedy decision, Gorsuch affirms the coach’s status as a sincere believer.

In Kennedy’s letter to school officials, written with the help of legal counsel, he claimed that “because of his sincerely-held religious beliefs,’ he felt ‘compelled’ to offer a ‘post-game personal prayer.’” Gorsuch quotes this portion of the letter, and continues, “He asked the District to allow him to continue that ‘private religious expression’ alone.” It is quite a misleading stretch (or a lie) to describe Kennedy’s actual actions—a prayer, surrounded by cameras and a “stampede” of supporters, following a national media tour—as private. It’s for that reason that Sotomayor includes photographs in a dissent: We can actually see the scene and it doesn’t look very private. But, for the court’s majority, all that really happened when Kennedy knelt was that an individual freely chose to follow his conscience, performing an essentially individual and thus private act of piety. There is no “society” here, no public in the picture.

Given the court’s atomized understanding of rights over consideration of others, the best response to its decisions is not to reassert the value of church-state separation or to lament the cracks in the wall. Instead, we should respond to the attacks on public education and the public good by reaffirming the human dignity of those too often marginalized from them. We should not abandon the ideals and promise of public schools, as Kennedy and Carson have both done. Instead, we ought to reinvest in public education. Spending is especially needed for teacher pay, buildings, learning materials, and other resources to create opportunities for learning and exploration. Arming public school officials or creating stricter disciplinary measures will only worsen the matter.

What Kennedy and Carson both signal, beyond the specific religious freedom issues, is the imperilment of the public good. Religious free exercise is increasingly antisocial, a way for individuals to insulate themselves from participation in society. But what disestablishment does, or should do, is create the conditions for an equitable public sphere, for a society where sectarian groups will not enforce orthodoxies on others, where people can be equal. A public school can be a place like that, too.

Perhaps the recent religion cases are, as some have alleged, the work of a theocratic court. Damning as that charge is, it might be too limited. The court’s aim, much like the conservative legal movement’s, is not theocracy but privatization. With privatization comes the license to discriminate more wantonly against those who have long had limited or no access to the public good and the resources that support it. The court’s conservatives do not oppose secularism so much as they oppose public things. And so, that is what we ought to defend.