In January 2021, Democrats got a little lucky: Defying expectations, the party won a pair of Georgia Senate seats, securing a razor-thin majority in the upper house. But even 50 seats in the Senate have not been enough for Democrats to pass any major legislation addressing climate change—especially with West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin occupying one of them and enough Republicans to mount a filibuster filling the other 50. While last year’s bipartisan infrastructure law included a smattering of green provisions, the Build Back Better Act, which included $555 billion for renewable energy and clean transportation, died at Manchin’s hand. What’s a president to do? If you’re President Joe Biden, one option is to look to the Defense Production Act.

Naturally, climate change is far from the only area in which the narrow Democratic majority has caused headaches for the White House and frustrations for members of Congress. Members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus have long been calling on President Joe Biden to take more executive actions to enact his goals. The downside of a president acting in this unilateral fashion is that no one stays president forever: Orders by one president can quickly be undone by the next. (Senate Democrats are reportedly working on a new bill that can be approved through the process of reconciliation without any Republican votes, which may include climate-related provisions, but such a measure has yet to be introduced.)

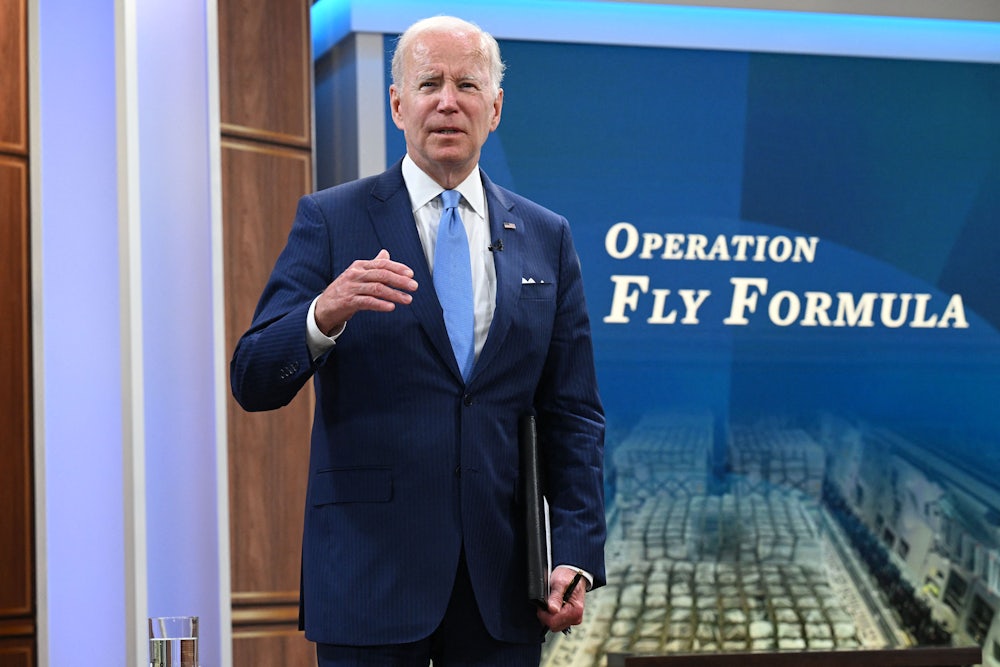

The Defense Production Act has become one of this White House’s go-to workarounds. Earlier this month, Biden invoked it to boost domestic production of solar panels. But this is hardly the first time Biden has relied on the 70-year-old law. Biden has triggered it multiple times in recent months, in response to such varied issues as the coronavirus pandemic, the baby formula shortage, and increasing production of electric vehicle battery materials. (It was also invoked by President Donald Trump in response to Covid-19.)

The Defense Production Act was passed in 1950 in response to the Korean War, granting the president broad authorities to mobilize domestic industries in the name of national defense. As the Congressional Research Service noted in a 2020 report, Congress “has expanded the term national defense” over the years, such that “authorities may also be used to enhance and support domestic preparedness, response, and recovery from natural hazards, terrorist attacks, and other national emergencies.” The government uses the Defense Production Act routinely to impel private companies to prioritize federal orders; the Defense Department places approximately 300,000 orders per year using the act. The Department of Homeland Security invoked the act around 400 times in 2019, primarily in relation to disaster response.

But use of the act can spur headlines when the president invokes it in a dramatic way, as with the recent action in boosting solar production. It also raises questions about the roles of the executive and of Congress in an era when legislating is hampered by the filibuster, which necessitates that almost all bills receive 60 votes to advance, making it incredibly difficult for the president to implement his agenda using legislative means. (The majority party may use the process of reconciliation to pass certain bills with 51 votes in the Senate, as Republicans did with their sweeping tax cuts in 2017 and Democrats with their $1.9 trillion coronavirus-response package in 2021.)

Molly Reynolds, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institute, said that increased gridlock in Congress has led to the president taking more executive action, which in turn can erode the authority of the legislative branch. “Even if in the short term it accomplishes some policy goals that members have, it really just further weakens congressional power,” Reynolds said.

Biden’s use of the Defense Production Act to boost solar panel production received a mixed reception from Democrats. The Progressive Caucus, having backed the idea of the president acting more unilaterally, welcomed Biden’s invocation of the act on energy issues in a statement last week. However, caucus chair Pramila Jayapal took pains to note that “the president’s leadership cannot substitute for lack of Congressional action.”

“There is simply no way to meet the president’s climate goals with executive action alone,” Jayapal said. “As the people’s representatives, we have a moral and governing obligation to fight the climate crisis and pass legislation that will facilitate our transition away from fossil fuels and support frontline communities.”

Senate Democrats insisted that the president was using the tools available to him but pushed back against the idea that Congress had ceded its authority to the executive branch. “I mean, I would like to be more involved. But you’ve got Mitch McConnell, who wants us to do nothing here. So the president of the United States should not be concerned about process, he should be concerned about getting things done. And so that’s why he does what he does,” Senator Sherrod Brown told The New Republic.

Senator Ed Markey said that any congressional proposals, such as the as-yet-unagreed reconciliation bill, would be “complementary” to the president’s actions. “Hopefully it winds up being a virtuous competition, where each branch is trying to do all it can to create the incentives to reduce greenhouse gases,” Markey said.

Senator Bernie Sanders, asked if he thought Congress was ceding its responsibilities on climate change to the White House, argued that this reporter was asking the wrong question. When asked what the right question would be, Sanders replied: “Did Biden do the right thing? Yes, he did. Is it pathetic that we don’t have the votes necessary in the U.S. Senate to address the existential threat to the planet? It’s very pathetic.” (In defense of my question, non–opinion reporters typically shy away from asking lawmakers whether their inaction on an issue is “pathetic.”)

Republican Senator Pat Toomey accused Biden on Twitter of “abusing” the Defense Production Act. “If the administration keeps misusing the DPA for non-defense purposes, Congress must curtail it,” Toomey said. According to the Congressional Research Service, Congress could take several actions to limit the scope of the law, including amending “the definitions of key terms found in the DPA to shape the scope and use of the authorities, especially the definition of national defense.”

Toomey later told The New Republic: “Congress has been ceding authority to the administration for decades, and it’s a huge problem.” When asked what could be done, he replied somewhat elliptically that “we should start taking back the authority that we’ve ceded.”

There is one area in which members of Congress are able to reach regular consensus: defense spending. While Congress can struggle to even fund the government in a timely manner, it has continued to pass the National Defense Authorization Act with limited drama every year, occasionally ponying up more money than the Department of Defense even asked for. Congress has also recently appropriated billions of dollars to aid Ukraine with large bipartisan margins. But while defense-related issues receive this largesse, Congress has struggled mightily to approve additional coronavirus-response spending to fight the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

While reaching agreements on defense spending may be easier for Congress than social spending, it may be reductive to say the legislative branch has fully ceded its authority on social and climate issues to the president. On Sunday, for example, 10 Democratic senators and 10 Republican senators announced an agreement on a framework on gun safety legislation, although an outline is far from legislative text, and the deal was far narrower than most Democrats would want.

“I don’t know if I would go as far as to say that in the future, it will be only a president who does things that are more on the nondefense side of the ledger,” Reynolds said. “But I do think the politics and policy of defense spending have kept those legislative muscles moving in Congress, when they’ve kind of atrophied in some other areas.”