Writing in the interwar gloom of the late 1930s, Cyril Connolly warned that “there is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.” It was a catchy encapsulation of an idea with ancient roots, that “good art” calls for monastic devotion and insulation from the trivial worries of the world and the flesh. Young children, however, are all flesh, demanding their own abundant measures of devotion, and merrily trampling peace, attention, and boundaries. How, then, can art and babies possibly co-exist?

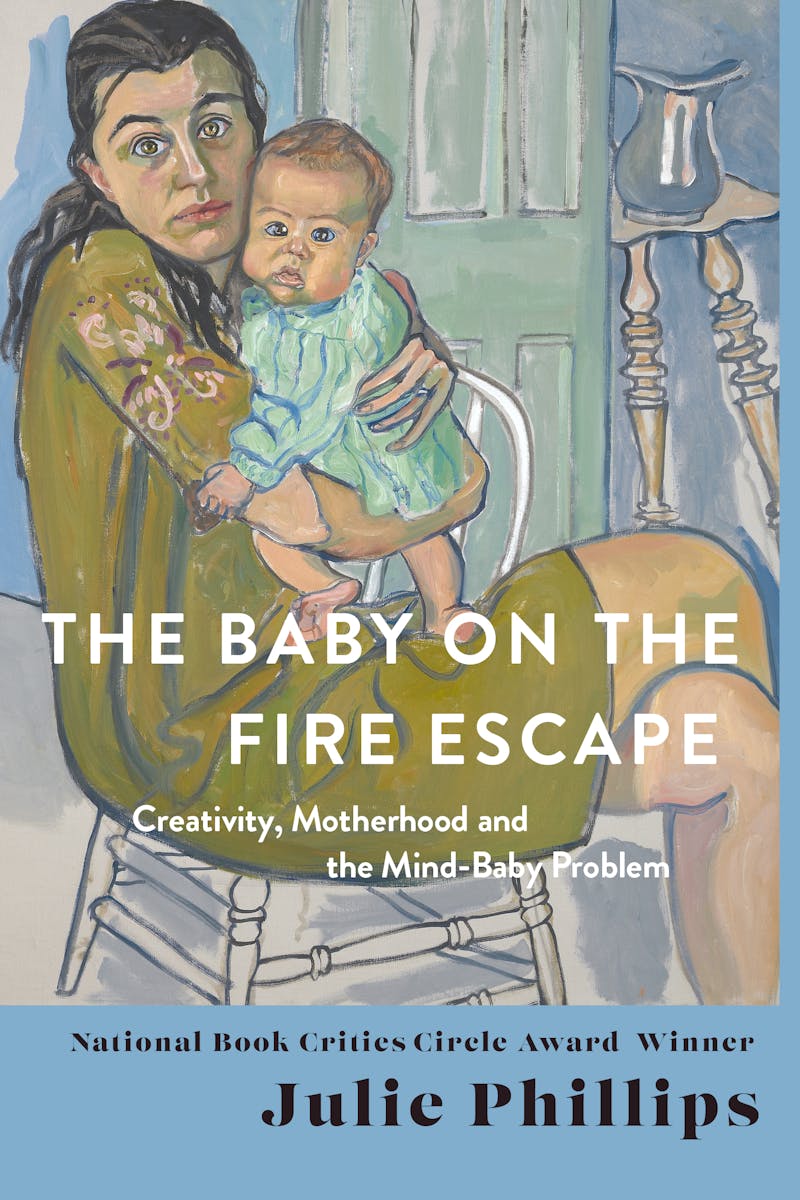

The title of Julie Phillips’s new book, The Baby on the Fire Escape, sounds like the artist-mother’s drastic response, shutting the baby outside so she can work without distraction or interruption. Yet, as it turns out, the picture is a false one: Phillips takes her title from an accusation of neglect that the painter Alice Neel’s upper-class in-laws flung at her to signal their disapproval of her parenting and bohemian lifestyle. Neel’s daughter—her second, after a baby who died of diphtheria—grew up mostly in the care of those in-laws in Havana. They apparently told her that her mother had forgotten her on the fire escape while she was busy painting, perhaps to prove that the struggle between art and children could have only one winner.

Neel is the first in a series of creative mothers sketched in Phillips’s thoughtful and heartfelt book, followed by the writers Doris Lessing, Ursula Le Guin, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, and Angela Carter. We get briefer glimpses at many others, including some whose embrace or escape of mothering is a well-known part of their life—Adrienne Rich, Susan Sontag, Shirley Jackson—and several whose stories may be less familiar. Their circumstances vary, though all of the central subjects are married for the first time by their mid-twenties. When the babies come, each mother carves out a space to work amid domestic life: a desk in the attic (Le Guin), with papers scattered over the bed (Sontag), or with the baby in a “little plastic chair” parked on the desk (A.S. Byatt). Alice Walker has a babysitter three afternoons a week, barely enough to remind her that she’s a poet as well as a mother. Everything she writes in the first year of her daughter’s life, she says, sounds “as though a baby were screaming right through the middle of it.”

Phillips grapples with the constant interruptions, divided loyalties, exhaustion, and relationship pressures of motherhood and tries to show how they can co-exist with “good art”; how we might get beyond Connolly’s notion that family life and creativity are locked in a zero-sum battle. The challenge is that mothering resists a coherent narrative, existing in glimpses, anecdotes, the baffled awareness that time is lurching on without you. Phillips aims to tell the story differently: If we could integrate the periods of interruption, silence, and failure into the narrative of a mother-artist’s life, she suggests, we might be able to see motherhood not as the end of creative life, but as a hero’s quest—with its adventures, setbacks, victories, self-discoveries, and relentless forward motion.

Born in January 1900 in small-town Pennsylvania, Alice Neel was among the first generation of female art students permitted to paint the nude male body. Nevertheless, she operated, as all women did, “in a society structured to keep them financially dependent,” in which their wages were set at a fraction of a man’s, and entry to higher-paying white-collar professions was mostly barred. It wasn’t impossible to make one’s way alone, but without family wealth it was a thankless grind, and required extraordinary powers of abstention from pleasure—getting entangled with a man could be a disaster for a woman who prized her independence.

Unsurprisingly, Neel fell in love anyway: with Carlos Enríquez, a sexually sophisticated, wealthy Cuban man, who wanted to be an artist himself and supported her ambition, up to a point. Their first daughter was born in Cuba the day after Christmas in 1926, and after a few months in her in-laws’ “gilded cage,” Alice and Carlos set up home in New York. It was, however, “too early in the world’s history for household equality,” as Phillips puts it, which is another way of saying that Neel’s husband, for all his bohemian posturing, was a man of his time, and would not do a woman’s domestic work. They were taking turns painting, but they needed money, and someone had to cook, clean, and take care of the baby. When their daughter sickened in the depths of the New York winter and died just before her first birthday, Neel’s guilt and grief twisted into an irrepressible drive for another child. Eleven months later, a second daughter was born, to a mother still lost in depression and desperation, still unable to reconcile what she called “this awful dichotomy” between her baby and her art.

Enríquez, grieving himself, took the new baby to his family in Havana, promising Neel that they would all reunite and go to Paris together. Instead, without telling her, he went alone, leaving the baby with his mother and sisters. In rage and despair, Alice collapsed. After almost a year of hospitalization, and doctors who insisted she choose between art and motherhood, she chose art, and made her way to Greenwich Village, while her daughter remained in Cuba. It was the start of the Depression, and Alice made portraits of the struggling, ordinary people she met in the neighborhood, imbuing them with sympathy and humanity. The WPA’s Art Project paid her, along with thousands of other artists, a living wage simply to produce and regularly submit her paintings. (“Socialism is kinder to mothers than capitalism,” Phillips notes.) Her relationships with men were turbulent, but in an effort of “family-making at the last minute,” around her fortieth birthday, she had two sons with two different fathers, and raised them in a cheap apartment in Spanish Harlem. Her social-realist portraits fell out of fashion during the macho abstract expressionist years, but she held on, struggling always for money, until late in her life she was hailed and celebrated. Her sons and daughters-in-law supported her work and burnished her legacy, but she was never able to repair the rift with her daughter.

The problem visual artists face has a physical dimension: They need space, as well as time. Following Neel, Phillips gives us glimpses of artist-mothers including Faith Ringgold, Louise Bourgeois, and sculptor Barbara Hepworth, who described raising her four children “in the middle of the dust and the dirt and the paint and everything.” Writers, on the face of it, have it easier, free to work anywhere, like Audre Lorde, scribbling “on scraps of paper that she stashed in [her daughter] Beth’s diaper bag,” or Toni Morrison, with her notebook on the passenger seat, writing in the stoplight pause. Yet it can be harder to claim the time you need, and to battle your own self-doubt. Are you really creating something that matters enough to neglect your baby? What about the time you have to spend staring into space? And what if nobody wants the story you write?

In the 1950s, Phillips describes a silence falling on creative mothers, as the steamroller drive for domestic conformity threatened to crush their artistic ambitions. Women who came to maturity as mothers and artists after World War II groped through a period of obscurity, in which women’s writing was out of fashion, belittled, or misunderstood. Some, like Doris Lessing, created a tough, macho literary persona to keep up with the angry young men; others, like Elizabeth Smart, drank with and slept with them, writing for money rather than art. “Silent years,” she called them. “Desperate from hating.”

Phillips reads Shirley Jackson’s horror fiction, her haunted houses and small-minded small towns, as reflections of her own alienation from domestic life. As the frantic mother of four children, with a “tyrannical and useless” husband, Jackson struggled to hold together her domestic facade, turning it into comedy, even as the ghosts of other lives, other stories, threatened to crowd out her sanity. The poet Gwendolyn Brooks, awarded the Pulitzer Prize’s $500 purse in 1950 just as her electricity was shut off, embarked shortly afterward on her only novel, 1953’s Maud Martha. It follows a young Black mother stifled by domesticity, her frustration compounded and turned to fury by the ugly places that redlining forces her—as it did Brooks—to live. Two years later, the “maternal horror story” of Emmett Till’s murder ignited feelings of powerless rage among Black women, which Brooks crystallized in her most powerful poetry.

These mothers’ stories rise and converge in the 1960s: In 1962, Alice Neel was the subject of a major profile in an art magazine for the first time, Susan Sontag saw her first essay in print, and Doris Lessing published her influential novel The Golden Notebook. The following year, Audre Lorde and Alice Walker both attended the March on Washington: Lorde, who had left her five-month-old baby for the first time, recalled being distracted by her sore breasts; a teenage Walker climbed a tree to hear the speeches better. By 1968, “Year One,” in Angela Carter’s words, the old order was cracking at the seams, antiwar protests and student uprisings roiling the world, while second-wave feminism and the civil rights movement roared with new urgency. Lorde accepted a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship to teach poetry at Tougaloo, a historically Black college in Jackson, Mississippi, where she met Frances Clayton, her partner for the next 17 years. At the end of the decade, Angela Carter won a book prize and used the money to leave her husband and travel around the world.

Both movements promised freedom, yet exerted pressure to use and celebrate it only in certain ways. Ursula Le Guin, who found family life enriching and nurturing to her art, chafed against the feminist dogma that motherhood meant patriarchal enslavement. The always contrary Alice Walker wrote that she found the increasing militancy of the civil rights movement exclusionary and judgmental, alienating her from women she believed to be allies. Married to a white man and living in the South when her daughter was born in 1969, Walker claimed that when the poet Nikki Giovanni visited her in Jackson, bringing her young son, she asked Walker how she could sleep with someone she wanted to kill.

In one vital way, however, the gains of the feminist movement affected women’s lives in allowing them to choose motherhood freely. Several of Phillips’s subjects—including Le Guin, Lorde, and Walker—ended pregnancies before Roe v. Wade. Le Guin was a college student in 1950, dating a Harvard boy who “knew for a fact that if you made love twice in one night you didn’t need to use a condom the second time.” Family support allowed her to go to a safe, discreet doctor on the Upper East Side, who charged the same as a year’s tuition, room, and board at Radcliffe, and to finish her education. The following year, teenage Audre Lorde took her chances with a nurse who induced a miscarriage for $40—two weeks’ pay for Lorde at the time.

Twenty years later, Angela Carter had a legal abortion after a one-night stand (“fecundated at hazard,” as she put it) and remained ambivalent about the idea of motherhood. When she finally had her son, she was able to count on day-to-day domestic help from his father, as well as the wisdom of her more experienced writer-mother friends, and she quickly got back to work.

Early on in the book, Phillips evokes novelist Jenny Offill’s figure of the “art monster,” which has become ubiquitous in contemporary discussions of motherhood and creativity. The art monster—in context, a female fantasy of what male artists are permitted to be—resists the petty pull of the domestic for the snarling single-mindedness of creative commitment. Phillips’s subjects have their moments of monstrosity, making desperate decisions, picking fights, raging against their confinement. Elizabeth Smart coped with her secret rage and her desire for women by using drugs, drinking heavily, and sending her children to boarding school. Fury is a common thread, even in mostly happy households: Lorde’s children remembered her getting “toweringly angry,” an anger that matched her caring in intensity. But instead of denying it, she tried to face the rage and use it, that “molten pond at the core of me.”

For Doris Lessing, the conflict between family and the life of the mind meant leaving one. At 23 years old, she had two toddlers. She had tried to get an abortion, only to be warned off by a friend of the doctor’s that he tended to operate drunk. It was the early 1940s in colonial Rhodesia, where a white woman of her class was not expected to have any intellectual curiosity, let alone political curiosity. Doris (and her husband, at first) had both, but hers burned unignorably, a lamp that she struggled, like the heroine of one of her autobiographical novels, to keep burning “above the dark blind sea which was motherhood.” The law in Rhodesia would grant her husband full custody if she left for any reason; she did it anyway, renting a room in the city and trusting—wrongly, as it happened—that he would let her see her babies. She threw herself into activism with the Communist Party, remarried, fell in love (with a different man), and had a third child. In 1949, she made her way to London, leaving the older children behind.

Phillips mostly resists the temptation to judge her subjects for their mothering choices, and her reading of Lessing is sensitive and sympathetic. Yet she flirts with judgment at times, especially in the short section on Susan Sontag. The “idea of Susan” is inspirational, Phillips writes, the forthright, famous, no-fucks-given intellectual, “but close up her admirers are often disappointed, or feel abandoned when she denies she’s gay.” Yet the photograph she includes—of Sontag at a custody hearing in 1964, dressed in a suit, with neat hair and neat heels, looking so much younger than she is, next to her son in his own little suit, looking much older than he is—is nonetheless startlingly revealing of the pressure she was under to pass as society’s idea of a respectable mother.

There is, of course, a far more hopeful, generative formula for mothering and art than the “art monster,” one in which motherhood enriches our experience and expands our imagination. Phillips celebrates Audre Lorde’s dedication to making her joy in her sexuality, her Blackness, and her motherhood visible when it was expected to be hidden, and her family as stable and conventional as any Ozzie-and-Harriet cliché. Lorde forged her own path, while Ursula Le Guin, the intellectual daughter of an intellectual family, grew up seeing domesticity as a site of curiosity, with big ideas debated around the dinner table and shelves loaded with books. Her own early motherhood was not without confusion and exhaustion, but her husband shared in it without question. Le Guin recalled him expertly pinning a diaper on “an extremely small shitty seven-day-old Elisabeth,” and, simply by his presence, helping her avoid what Doris Lessing in colonial Salisbury (now Harare) recalled as the “Himalayas of tedium” of mothering an infant.

That all-consuming experience of caring for helpless, shitty babies is of course not endless at all, though it feels that way. It changes and eases, and time opens up, and mothers can come back to work with renewed focus. Phillips’s book is astute on the long careers, and the full lives, of her creative women. Penelope Fitzgerald published her first novel at 60; Angela Carter resisted motherhood until the age of 43. Carter’s most celebrated collection of stories, The Bloody Chamber, reimagines classic fairy tales to give power to women; to be a woman, in her fiction, means mixing with myths and monsters. Although cultural clichés have long presented motherhood as an unchanging state, a woman’s apotheosis, Phillips argues instead that its essence is transformation. By the time the mother of the baby on the fire escape has become the guardian of an empty nest, she has ventured out, fought monsters, faced fears, and become a new version of herself. If we looked differently, Phillips suggests, wouldn’t hers be a “hero-tale,” her quest as bloody and noble as any knight’s?