The bacchic chant of self-congratulation fills America over the way the Constitution has triumphed, allowing us to replace the amoral Nixon with the openhearted Ford. Indeed, a noxious cloud has lifted. But does that vindicate our system? We must dissent.

Here is a press release from the Democratic Study Group (Report 13, Supplement 1) dated October 18, 1972, a fortnight before the election. For some reason we have saved it. It is headed “The Most Corrupt Administration in History,” quoting George McGovern. It outlines the latest scandals of the Nixon administration (spelling Kalmbach as “Klamback”) and denounces the assertion of Republican innocence: “The White House,” it marks, “issued a blanket statement claiming that no White House aides were involved.”

It was too late for McGovern then. The evidence was there but nobody believed it. Nemesis took two years.

Now the scandal is lanced, Nixon is out, and in the fervent national sigh of relief the result is said to “vindicate the system.” But where does this leave the constitutional process of impeachment? Its threat certainly caused the President to resign, but only after he had convicted himself. Will any other culprit so conveniently testify against himself in his own tapes? Nobody has so trapped himself for self-destruction since Shylock and his pound of flesh.

With a scandal like this almost any other government would have fallen and there would have been a national election, but lacking such a device we used the procedure of hue and cry. It convulsed the nation and almost interrupted orderly administration. And the climax did not bring a change of government but only a change of faces. No new mandate was formally ratified by the voters; and when Mr. Ford picks his new Vice President (confirmed by Congress) it will be a double selection in which the people had no part.

Mr. Ford makes the best of it: if he has no electoral obligation to voters, he notes with justice, neither does he have obligations to favor-seeking giant corporate contributors. He has won without them. This is true, but when you analyze it it means that if we don’t have democracy we have something almost as good.

The Nixon resignation leaves the impeachment device in limbo. And it postpones indefinitely any hope of a constitutional change that would allow a popular election on a no-confidence vote.

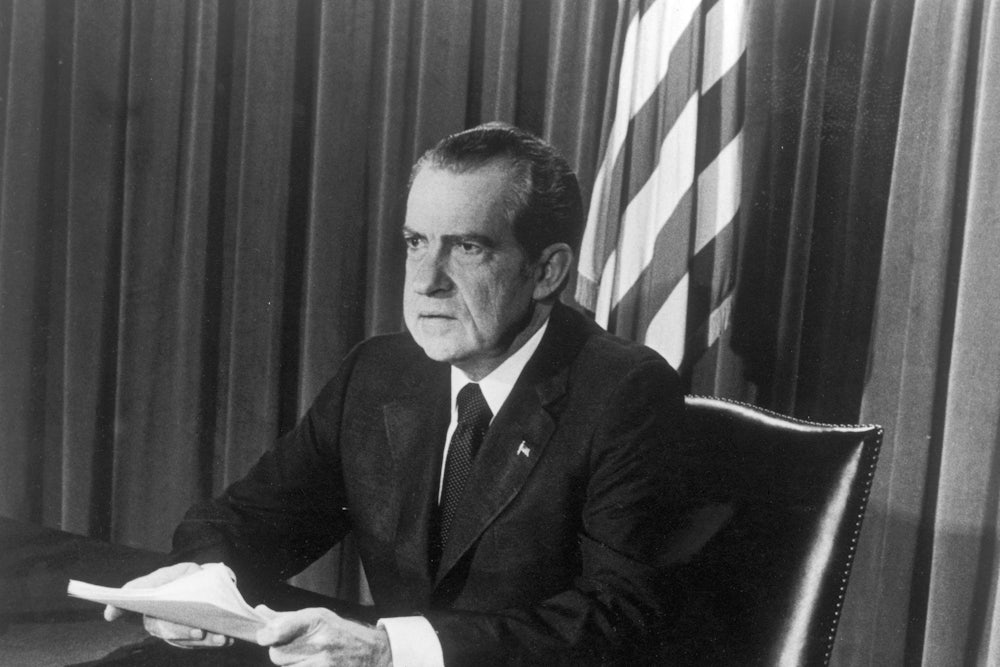

How does an undesirable like Nixon get to be President in the first place? His record was pretty well known (if former Nixon admirers will forgive us for saying so). His tactics were those of war, not normal politics. He distrusted everybody. But he won an overwhelming vote in 1972.

Here was a President who regarded Americans as “children,” and who let his lawyer and 10 loyal Republicans on the Rodino committee defend him, at considerable risk, only to find out at the end that he had known about the cover-up all the time.

Compassion is a wonderful thing; it was urged after the Grant and Harding scandals by men who profited by it, and who went on to win the next presidential election for their party despite the scandal. Once again we have a Mr. Clean, and pleas to forget the past.

Mr. Nixon does not himself admit guilt. In a tearful farewell to the White House staff he boasted that nobody left his administration “with more of this world’s good than when he came in”; a rather inapt phrase from one who underpaid his taxes by $465,000. Nobody wants to be vindictive. But the Ervin committee leaves 377 pages about the mysterious Nixon-Rebozo relationship, the donation of recluse billionaire Howard Hughes of $100,000 (in $100 bills) after receiving antitrust favors in Las Vegas, and a 30-page “summary analysis of conflicting evidence” which leaves little doubt that somebody is lying; somebody has committed perjury. It is all very well to be compassionate but the continuing grand jury can’t drop its inquiry. There is circumstantial evidence that leftover campaign contributions passed through three Rebozo-associated trust accounts in Florida and ended up as Pat’s diamond earrings. If all Americans are equal under law these matters can’t be dropped, no matter how much Mr. Nixon has suffered.

So that brings us at last to Mr. Ford. What a relief. The nation is like a child that has swallowed something nasty and thrown up and feels better. Mr. Ford is everything that Nixon wasn’t, with warmth and openness and decency, and he has engendered nationwide affection. (We don’t hold it against him that he too lunches on cottage cheese garnished with catsup.) Emotions on his face are as transparent as on Eisenhower’s.

But what are his limitations? He is more conservative than Nixon and more consistent at it; Nixon steered by a wet thumb, but Ford has a compass pointing always to right of center. He inherited his economic advisers from Nixon; they are associated with business and Wall Street. We wonder about Alan Greenspan, Nixon’s chairman-designate of the Council of Economic Advisers, who testified before the Senate Banking Committee in confirmation hearings last week that he opposes the antitrust law, and doesn’t believe in the graduated income tax.

President Ford is a conservative and not, we think, very smart at it. Name almost any piece of civil rights, welfare or social legislation in the past 20 years—he voted to weaken or kill it. Name any proposal to spend money for Vietnam or the Pentagon—he voted for it. He attacked LBJ for not pushing Vietnam bombing. When Democrats blocked Carswell he tried to impeach liberal Justice William O. Douglas declaring that “an impeachable offense is whatever the House of Representatives considers it to be.”

The nation is in extraordinary economic peril, inflation of wholesale prices last month was at the annual rate of 44 percent. Very likely our standard of living will decline in the next two years. The poor will suffer most. In Congress, Ford was never innovative or imaginative; he offered no legislation of his own; he was a lineman on the team, not one who called the signals. While decent, he was also stubborn. Now his formula is budget cutting, on everything but defense. We fear this oversimplifies his problem.