You may have heard the just-so story about environmentalism as we know it. On Christmas Eve 1968, an astronaut aboard NASA’s Apollo 8 spacecraft took a photograph of the faraway surface of a green-and-blue, cloud-marbled planet known to its English-speaking inhabitants as Earth. Published less than a week later on the front page of The New York Times, the image set off a general ecological awakening. The lesson was: Behold the fragile jewel that is your one possession and cherish it accordingly. “Within two years of this picture being taken, the modern environmental movement was born,” Al Gore explained in the book version of An Inconvenient Truth (2006). Gore is one of many to tell the tale, which I most recently encountered in a book by the economist Diane Coyle on the statistical measure known as GDP: “Seeing the earth from space had given us a vivid new perspective,” prompting “concerns about the effect of economic growth on the environment and the planet as a whole.”

Such claims invite skepticism. Can a photo really induce instantaneous enlightenment? As it turns out, climate change and resource depletion have accelerated, not slowed, since publication of the “Earthrise” photograph. Nor has the basic ambiguity of the image been noted often enough: The photo may have encouraged new environmental commitments, but to take it at all entailed leaving the planet behind—much as tech billionaires like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, with their fantasies of colonizing space, now imagine humanity doing on a more permanent basis. In this way, an ostensible portal to ecological salvation contains a different implication—in which Earth is, Eurydice-like, glimpsed only to be lost and abandoned. But to enter these objections may be to pitch criticism of the “Earthrise”-as-Eureka meme at too high a level. Prior to 1968, it was by no means unheard-of to encounter mounted globes of the planet, in classrooms and elsewhere. Spin one of these and you can see the whole terrain, as isn’t the case with a photo.

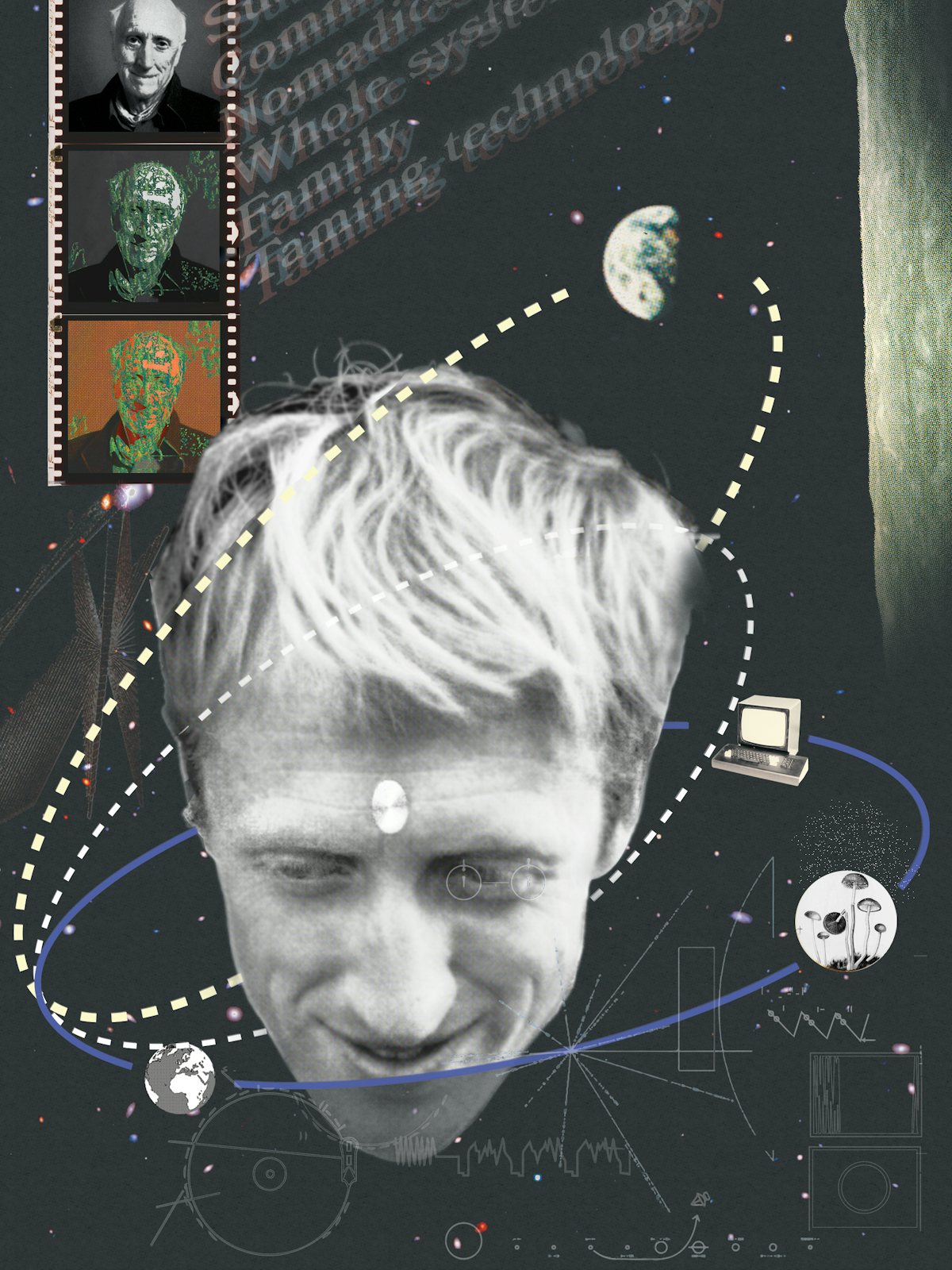

The notion that a revolution in consciousness ought to follow from whole-Earth imagery is most closely associated with Stewart Brand, the Bay Area networker, publisher, booster, and impresario who, toward the end of the 1960s, launched the countercultural handbook the Whole Earth Catalog and, almost two decades later, founded the Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link (WELL), an important precursor to the internet. As veteran tech journalist John Markoff recounts in his biography, Whole Earth: The Many Lives of Stewart Brand, a vision came to Brand after he took LSD on a San Francisco rooftop in 1966. Floating up over the city, in his acidulated imagination, and then beyond the atmosphere, Brand felt a light bulb the size of the globe switch on: “Seeing Earth from space would transform the way we view our planet and ourselves.” All was one and everything was connected. Brand would soon put together a plywood sandwich board emblazoned with the vaguely paranoid query WHY HAVEN’T WE SEEN A PHOTOGRAPH OF THE WHOLE EARTH YET? in Day-Glo letters, and wear it, along with a white jumpsuit and feathered top hat, to college campuses.

It was Brand who, in the fall of 1968, scooping The New York Times by several months, put a NASA satellite photo of the planet on the cover of his first issue of the Whole Earth Catalog. In tones of somehow giddy responsibility, an early editorial note suggested that human beings held the planet in their hands: “We are as Gods and might as well get good at it.” More practically, Brand’s semiannual catalog would function as a sort of Sears-Roebuck resource for hippie homesteaders, enabling them to set up their lives after their own fashion, beyond the administered patterns of bureaucracy and suburbia.

Yet this vision of an interconnected planet ultimately led Brand, now in his eighties, beyond the 1960s idyll. As a hippie sage, he’d proposed a DIY counterculture as the logical expression of a properly planetary point of view. Later on, his enthusiasm for the burgeoning internet suggested to fans such as Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos that, in fact, it was a global network of communication and commerce that best embodied the truth that the world is a single entity made up of interconnected inhabitants. The title of Fred Turner’s 2006 study, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and The Rise of Digital Utopianism, neatly captures the arc of Brand’s singular career. It also poses the question of whether the cyberculture of the 1980s and beyond should be seen as a betrayal or, instead, a fulfillment of the counterculture of the 1960s. In both periods, Brand insisted on placing the relevant “tools”—whether psychedelic drugs or personal computers—in the hands of individuals. And in both cases, he hoped the result might be a world of newfound individual satisfaction and collective responsibility.

Born in 1938, Stewart Brand preceded by more than half a dozen years the earliest of the baby boomers. If the boomers were a generation whose outlook and trajectory he often seemed to anticipate—from early countercultural forays, to a later embrace of PCs and the internet, to a final accommodation with big business—it must have helped that in relationship to them he possessed the confidence and sophistication of an older brother, without ever projecting the authority of a parent.

Brand’s hometown, Rockford, Illinois, furnished the subject of a 1949 photo essay in Life, because the magazine’s editors judged it the most typical city in the country. And the Brand household does seem a distillate of postwar America. Brand’s father was a partner in a local advertising firm—much as Brand himself would later operate as a publicist for countercultural ideas and products. In the father’s ham-radio hobby, it’s also possible to spy the son’s future embrace of the personalized, as opposed to bureaucratic, employment of technology. As for Mrs. Brand, a Vassar-educated homemaker and “space fanatic,” her passion for exploration of the New Frontier recurs throughout her son Stewart’s life, from his boyhood attachment to a book called The Conquest of Space onward. In recent years, Brand traveled with Jeff Bezos through the Western United States to find a site for Blue Origin, Bezos’s aerospace company.

The brightest thread running from Brand’s youth to his later years may be the individualism he articulated in a diary entry from 1957, when he was still a teenager. Should the United States and the USSR come to blows, he told himself, “I will not fight for America, nor for home, nor for President Eisenhower, nor for capitalism, nor even for democracy. I will fight for individualism and personal liberty.” Such Cold War self-reliance was complicated, however, by Brand’s classes at Stanford, where he majored in biology: “At long last,” he wrote his parents, “I’m getting what I was looking for in biology: ecology, ‘the interrelation between living organisms and their environment ...’ This is the ‘living whole, not the dead parts.’” Much of the organizing tension of Brand’s life—as a promoter of environment and community, on the one hand, and of technologically equipped personal freedom, on the other—comes from his efforts to square his youthful individualism with the ecologically minded holism he discovered in college. The Whole Earth Catalog would call for planetary life to be seen as one integrated system and, at the same time, seek to release its readers into splendid isolation, through “access to tools for self-dependent self-education, individual or cooperative,” as early copy had it. The question has always been whether these two aims were complementary, as the Catalog suggested without really stating as much, or contradictory.

In June 1960, Brand, the future icon of the counterculture, attended Stanford’s commencement ceremony in his Reserve Officers’ Training Corps dress uniform. Little about the next two years he spent in the Army appealed to him, besides the opportunity to take photographs from a C-123 transport plane. According to Markoff, he passed the bulk of his time at Fort Dix, in New Jersey, attempting, without success, to use “his skills with a camera and typewriter” to secure a new posting in Europe, as a military photographer or public affairs officer. Unsurprisingly, Army life chafed against Brand’s individualism. Drawing on several dozen interviews with its subject over four years, Whole Earth comes across as something like a third-person memoir, and here as elsewhere Markoff sticks to Brand’s point of view: “Right here in America [Brand] was experiencing regimentation, pettiness, and institutionalized stupidity—all the attributes he hated about communism.” Granted early release from the Army to study photography at the San Francisco Art Institute, Brand packed up his VW bus and, in August 1962, lit out for the Bay Area.

Within a few months, the former second lieutenant was regularly ingesting considerable quantities of LSD under the auspices of the International Foundation for Advanced Study, in Menlo Park. As Brand, who would take acid throughout the ’60s, wrote to a friend: “I vote Yes on drugs. Yes with huge capital letters that spill over into everything else.” Less rhapsodically, he also defended psychedelics in a letter to his concerned parents back in Illinois, who, in spite of their misgivings, continued to subsidize Stewart’s bohemian lifestyle: cheap San Francisco lodgings; hallucinogenic socializing; and a more or less stalled journalistic career, consisting in large part of failed pitches to The New York Times.

Like many people in his Bay Area milieu, Brand associated psychedelics with the possibility of a new kind of society lying beyond the staid, salaried, hierarchical variety he’d inherited as a child of the postwar Midwest. After a friend who had participated in enough indigenous peyote sessions to acquire the title of a “roadman,” or leader of peyote meetings, introduced Brand to the drug, he ate peyote buttons in the company of Navajos in Arizona and New Mexico. The experience fortified Brand’s penchant for big-picture consciousness, ratifying “his conclusion,” as Markoff puts it, “that for whites, time was a rapid sequence, whereas Indian life was land time. It was geological and astronomical.” Brand soon requested and received admission into the Native American Church, complete with membership card.

In 1964, Brand’s attraction to indigenous society converged with his training as a photographer to produce a portable multimedia spectacle or “ambitious traveling sensorium,” in Markoff’s words, called America Needs Indians! In miscellaneous venues around the Bay Area (a courtyard, a nightspot, an architect’s studio ...), Brand would project on a pair of screens photos he’d taken on Indian reservations, as well as images of middle American life, to a soundtrack of chanting and drumming. “One of the first multimedia exhibitions defining an emerging American counterculture,” in Markoff’s description, America Needs Indians! was screened at one of the Bay Area psychedelic parties that Ken Kesey called his Acid Tests. The work’s message seems to have been that the audience might learn to emulate the Indians’ communal, rooted, ecstatic life. “To many of us—white kids who had grown up watching Westerns in the fifties—these revelations struck like lightning bolts,” recalled Phil Lesh, the bassist for the Grateful Dead, house band for the Acid Tests. Before long, Brand, with his talent for networking, was helping Kesey to organize a successor happening, the Trips Festival, at San Francisco’s Longshoremen’s Hall.

Brand and Lois Jennings, the half-Ottawa mathematician who would become his first wife, promoted the Trips parties wearing what Markoff calls “Native American regalia.” Revolutions, whether real or merely would-be, typically present themselves as reviving the spirit of some previous historical period, and, during the ’60s and ’70s, the real or would-be cultural revolution that came to be called the counterculture often liked to invoke pre–Wounded Knee Indian societies for this purpose. The geographical shift of the counterculture, circa 1970, away from cities and college towns and toward rural communes, only reinforced this tendency, for the obvious reason that the indigenous peoples of North America (at least after the abandonment of cities like Cahokia and Tenochtitlan) lived on the land rather than in conurbations.

No publication flattered this back-to-the-land shift more than the Whole Earth Catalog, started in 1968 with the decisive assistance of an inheritance from Brand’s adman father. Consisting of information “continually revised according to the experience and suggestions of CATALOG users and staff,” the publication turned its readers on to how to order farm implements and carpentry tools, Volkswagen repair manuals and Carlos Castañeda novels, bamboo flutes, calculators, Army surplus jackets, and potters’ wheels, as well as larger “tools” like canoes and geodesic domes, all with the idea of facilitating a hazily indigenous rural self-sufficiency, along somehow modern lines. In this, it drew inspiration from Aquarian settlements in rural Colorado, New Mexico, and elsewhere, with names like Drop City, Libre, and the Lama Foundation, which promised to bring communitarian self-sufficiency and environmental stewardship into harmony. The idea appealed to many more counterculturalists than those who actually decamped to the countryside, as a vision of the good life—good for you and good for the planet, too—they might one day realize.

A contradiction inhabited the heart of the project. In From Counterculture to Cyberculture, Fred Turner writes that the back-to-the-landers who “embraced the notion that small-scale technologies could transform the individual consciousness and, with it, the nature of community” also “celebrated imagery of the American frontier. Many communards saw themselves as latter-day cowboys and Indians, moving out onto the open plains to find a better life.” Much as Brand and the readers of his Whole Earth Catalog did, the passage confounds settler colonialists with the indigenous people they displaced, as if these antagonistic parties were one and the same. In retrospect, the back-to-the-land movement consisted of cowboys (in the sense of transient settlers, with an unsustainable relationship to the earth) who liked to imagine themselves as Indians (in the sense of a rooted and symbiotic relationship to nonhuman life). The movement’s rural communes almost all succumbed to bankruptcy or strife before the 1970s were out, and expired. By that time, Brand himself had noticed that compact cities made for a more efficient use of energy and materials anyway.

Brand has been a compulsive founder of new institutions—from the Whole Earth Catalog’s more intellectual heir, CoEvolution Quarterly (1974); to the digital community known as the Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link (1985); to a corporate consultancy, the Global Business Network (1987); and, finally, to something called the Long Now Foundation (1996). In the fall 1975 issue of CoEvolution Quarterly, Brand ran 25 pages of stories on “space colonies”: “Practical, Desirable, Profitable, Ready in 15 years,” announced the cover. The physicist Gerard K. O’Neill insisted that “Space Colonies show promise of being able to solve, in order, the Energy Crisis, the Food Crisis, the Arms Race, and the Population Problem.” Such extraterrestrial environmentalism provoked indignant responses from many of Brand’s readers. It was clearly less the gesture of a self-created Indian than that of a cowboy, with a taste for new frontiers.

Brand had imagined the Whole Earth Catalog not only as a clearinghouse for information on useful commodities but, through the publication of letters and product reviews from its readers, as host to a geographically diffuse, nonhierarchical community. In this sense, the Catalog can be seen as a sluggish, analog anticipation of the internet: In 2005, Steve Jobs, who often invoked Brand as an inspiration, described it as “Google before Google.” Living among the computer programmers of the Bay Area, Brand was well-placed to hail the emerging cyberculture of the last quarter of the twentieth century, and in a 1972 article for Rolling Stone he’d already announced: “Ready or not, computers are coming for the people.” As a magazine publisher familiar with the travails of manual typesetting and longhand bookkeeping, the Brand of the early 1980s found word processors and spreadsheets the most immediately mind-blowing feature of PCs. More astutely, he also perceived that a web of networked personal computers could—like the Whole Earth Catalog, but at a different scale and speed—bring into being specialized and temporary communities of far-flung people, united by shared interests: the sort of thing familiar to us today as Reddit forums or Facebook groups.

In the early ’80s, Brand joined the faculty at the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute in La Jolla, which pioneered “the use of teleconferencing,” as Markoff says, to bring together scholars in various related fields. This experience led to Brand’s establishment of the Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link, which charged its users’ credit cards a few dollars each month so that from their separate terminals they might participate in digital “newsgroups” on whatever subjects interested them. For reasons of both personal liberty and legal liability, WELL users retained title to their own content (“you own your own words”). In practice, they didn’t discuss ecology or geopolitics or even technology so much as the Grateful Dead, a band beloved by hippies and programmers alike.

The savvy Brand also gave tech journalists access for free. The idea was that an amorphous, leaderless, nonhierarchical flock of discussants of anything and everything would shepherd one another toward a continuously better-informed state of mind. “On the one hand,” Brand stood up and said at a Hackers Conference in 1984, “information wants to be expensive, because it’s so valuable.... On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of getting it out is getting lower all the time.” Both aspects of the statement proved prescient: Here was a casual prophecy of the expensive IP (vaccine recipes; superhero franchises ...) and cheap posting habits of our own digital culture. It’s less easy today to endorse what Brand told a San Francisco journalist around the same time: “When you communicate through a computer, you communicate like an angel.” Angels must delight in bandying about ill-tempered fallacies more than theologians had suspected.

Over recent decades, Brand has become less a prophet than a consultant. Through his Global Business Network, “THE ELECTRIC KOOL-AID MANAGEMENT CONSULTANT,” as a Fortune profile called him, has counseled corporate boards on flexibility, adaptiveness, and learning. Here were the familiar precepts of neoliberal capital—a regime ever more spontaneous as to organization, and ever more unequal as to money and power—in Brand’s preferred idioms of biological evolution, systems theory, and self-education. Markoff writes that GBN “rose to prominence based on several big ideas: that globalization would change everything, computer networks would change everything, and the internet would change everything.” These two or three ideas are also, in another way, none. To predict that everything will change is not to identify the differential components of transformation and persistence that make any emergent phenomenon, including global capitalism, legible at all. At most, pointing hectically to globalization indicates the setting—Brand’s whole Earth again—of the titanic development.

Stewart Brand is an earnest and serious-minded person. Nevertheless, one of his moments of illumination, as related by Markoff, caused me to laugh out loud. Here Markoff recounts the courtship of Brand and Patty Phelan, his second wife, in the 1970s: “Brand and Phelan lay on a hillside in the late afternoon sun. He had taken off his shirt, and he suddenly realized that she had taken off hers as well. Phelan, who was living with someone else at the time, had fallen for Brand head over heels, and it would soon be apparent that he had finally found his great love.” It’s as if the baring of Phelan’s breasts unveils, at one fell swoop, a destined and enduring love.

Everyone knows that breasts lie under women’s clothing in much the way that everyone knows that Earth is a frail blue dot zooming through space: These things are always the case, only mostly you don’t see as much. Nothing is so hippieish about Brand as his sense that radical improvements to life as we know it derive naturally, or at any rate ought to, from sudden, flashing revelations of the already known, glimpsed as if for the first time. The principal undertaking of Brand’s Long Now Foundation, the main preoccupation of his later years, has been to build, with funding from Jeff Bezos, an enormous clock that chimes only once a century, with the aim of promoting “long-term THINKING” of the kind otherwise in short supply in the twenty-first–century United States. Like the planet in its entirety, deep time is always there, and often overlooked.

Brand has surely been right in believing that to register the full dimensions of Earth, and the whole span of historical and evolutionary time, would be the start of wisdom. The trouble is that this enthusiast of new beginnings so often mistook such preliminary awareness for a meaningful conclusion. The revolution in consciousness promoted by Brand forever toggled between two vastly different scales: the planetary, and the individual. Its great shortcoming was that it never learned, or seriously studied, how best to integrate the two scales—that of the liberated individual, on the one hand, and the imperiled planet, on the other—through human institutions on an intermediate scale. There was only the dead end of the commune, or the default of the corporation. And so a kind of smog of dissipated insight hangs over Brand’s life and that of the boomers. You might even say it covers the earth.