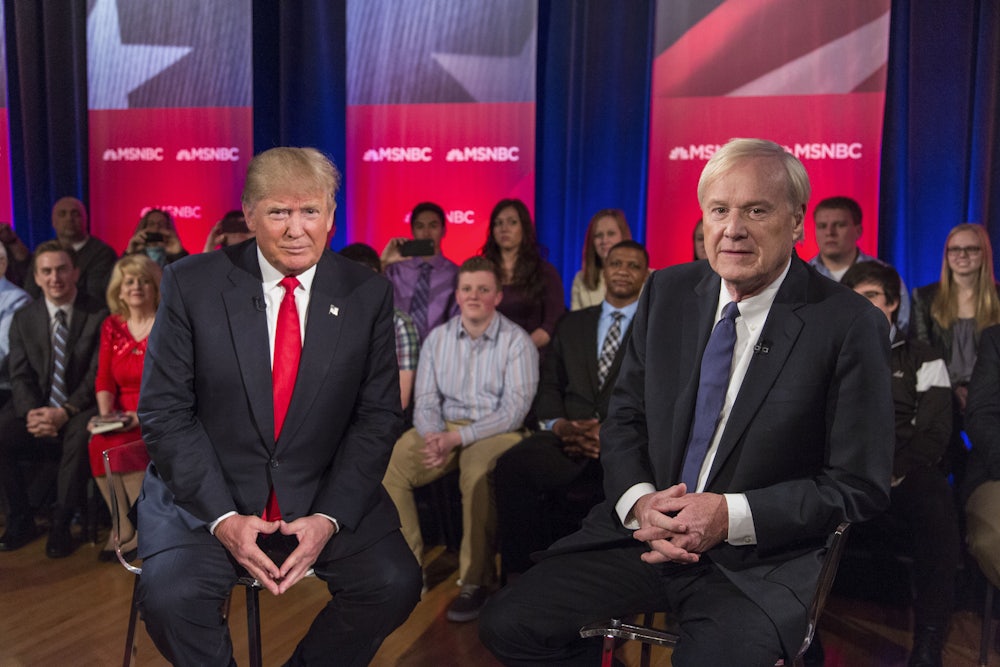

In March 2016, when asked for the specifics of his proposal to outlaw abortion, at an MSNBC town hall, then-candidate Donald Trump dodged: “This presidential election is going to be very important,” he said, “because when you say what’s the law, nobody knows what the law’s going to be; it depends on who gets elected. Because somebody’s going to appoint conservative judges and somebody’s going to appoint liberal judges depending on who wins.” Moments later, a clearly out-of-his-depth Trump stumbled too far, saying, “There has to be some form of punishment” for women who have abortions. His campaign quickly muddied the water with a statement calling the issue of abortion “unclear” and asserting that the matter should be “put back into the states for determination.”

Even by Trump standards, the position that women should be punished for abortions was stunning. But just as stunning was Trump’s assertion that nobody knows what the law’s going to be.

Trump wasn’t talking about a law—judges don’t make laws. He was talking about Roe v. Wade, which, along with Planned Parenthood v. Casey, is the Supreme Court decision that has undergirded the right to an abortion for five decades. Roe v. Wade is arguably the most well-known decision in the history of the judicial branch. At the time Trump made those remarks, the “law” had stood for just over 43 years, during which time it had withstood five Republican administrations. But now, six years later, Trump’s prediction has proved correct. Nobody knows what the law’s going to be. But the idea that women should face punishment for abortion, which was unthinkable way back when Trump first mused about the possibility, is suddenly on the table.

When Trump asserted that women should be punished for abortions, the remark betrayed what should have been an obvious truth: Donald Trump was blindingly unfamiliar with the basic tenets of the pro-life movement. The March for Life immediately issued a statement saying, “Mr. Trump’s comment today is completely out of touch with the pro-life movement.… No pro-lifer would ever want to punish a woman who has chosen abortion.” Nobody expected Donald Trump, a braggadocious womanizer who once co-sponsored a pro-choice benefit dinner, to be familiar with the specifics of the anti-abortion movement. But his remarks also betrayed the fact that he was only just beginning to understand the one-issue voting bloc it commanded. He understood that his own electoral fortunes depended on its support, but he hadn’t been coached in its language.

If you watch the 2016 town hall event again, you can see that in the moment before Trump asserted that “there has to be some form of punishment” for women who have abortions, he runs the calculation in his head. He visibly buys time, gazing away and trailing off with “the answer is that…,” before karate-chopping the air as if trapping his position. When he appeared on Face the Nation two days later for a damage-control clarification, Trump said, “I’ve been told by some people that was an older-line answer.” When asked how abortion law should be changed, the Republican front-runner responded confidently, a coached response: “At this moment, the laws are set. And I think we have to leave it that way.”

But Trump can be forgiven for believing the anti-abortion community wanted to hear that women should be punished for having an abortion. If you examine the movement from the outside, look at its tactics and state-level legislation, you might easily arrive at the conclusion that it blames women for having abortions.

Anti-abortion activists so often rely on the tactic of shaming women considering abortion. They hold signs and shout about eternal damnation outside abortion clinics. These may not be March for Life–sanctioned anti-abortion protesters, but they’re anti-abortion protesters nonetheless. Literature aimed at convincing women against abortions often looks similar to literature aimed at convincing high schoolers against driving drunk. Whether it’s a car wrapped around a telephone pole or an aborted fetus at 15 weeks, you don’t know quite what you’re looking at. But you sense somewhere in that carnage is an emotional reaction.

Those same shaming tactics have worked themselves into state legislation. According to the Guttmacher Institute, six states require an abortion provider to perform an ultrasound and to explain and describe the image. Many of these laws were passed recently. Over the past decade, the anti-abortion movement’s decades-long grassroots efforts have paid huge dividends. In 2011, a record-setting 92 pieces of legislation aimed at restricting abortion were enacted at the state level. In 2012, that number dropped to 43—but it was still the second-highest figure since Roe v Wade.

Trump’s unfamiliarity with the anti-abortion movement’s lexicon and policies also highlights the complexities of its language. The movement speaks in black and white—life is a human right; abortion is murder. And it’s become expert at framing those black-and-white issues. In 1995, the National Right to Life Committee devised the term “partial birth abortion” to explain a rare procedure known in the medical community as “dilation and extraction.” Later that year, Florida Republican Representative Charles Canady introduced the first federal bill outlawing “partial birth abortion.” The bill was twice vetoed by President Bill Clinton, but in 2003, a revised version was signed into law by President George W. Bush. It was the first law to limit a specific abortion procedure in the 30 years since Roe v. Wade.

In 1996, the National Right to Life Committee’s legislative director told The New Republic, “We would hope that, as the public learns what a ‘partial birth abortion’ is, they might also learn something about other abortion methods and that this would foster a growing opposition to abortion.” In 2000, the Guttmacher Institute estimated that dilation and extraction accounted for 0.17 percent of the abortions in the United States.

Though the anti-abortion policy shops of Washington spouted outrage at Trump’s position that women should be punished for having abortions, they eventually signed onto his White House bid. Marjorie Dannenfelser of the Susan B. Anthony List, a woman who has spent decades pursuing a dream of overturning Roe and commands huge power in the anti-abortion movement, led the Trump campaign’s “pro-life coalition.” She agreed to the role on the condition that Trump sign a pledge to nominate anti-abortion justices to the Supreme Court. Trump signed, and the anti-abortion movement backed him.

Dannenfelser’s role was announced in September 2016. In the letter (uploaded to the Susan B. Anthony List website but on Trump campaign letterhead), Trump committed to “nominating pro-life justices to the Supreme Court.” During the third presidential debate, only a month later, it was clear that Trump had been coached in the lingua franca of the anti-abortion movement. But in typical Trump fashion, he had made its message his own. When asked about abortion, he disregarded the policy-speak and went straight to making an emotional appeal, saying, “In the ninth month, you can take the baby and rip the baby out of the womb of the mother, just prior to the birth of the baby.” Hillary Clinton responded with workshopped language, complaining, “That is not what happens in these cases, and using that kind of scare rhetoric is just terribly unfortunate.” Trump watched gleefully, a rare instance of him remaining wisely silent.

The anti-abortion think tanks of Washington and its leading figures like Dannenfelser were eager to note that “no pro-lifer would ever want to punish a woman who has chosen abortion.” But when they came on board, they probably should have realized that Trumpism doesn’t accommodate nuances. Trump came not with a paintbrush but with a stick of dynamite. And so it should be no surprise that Trump’s faithful—which includes a swelling number of state legislators—don’t always fall in line with the policies of the swamp’s think tanks.

Only days after the Roe v. Wade opinion was leaked, a statehouse committee in Louisiana cleared a bill that would categorize abortions as homicide, allowing prosecutors to punish women for having abortions. The language in that bill is specific: to “ensure the right to life and equal protection of the laws to all unborn children from the moment of fertilization by protecting them by the same laws protecting other human beings.” In Louisiana, first-degree murder is defined as “the killing of a human being” and carries a penalty of “death or life imprisonment at hard labor without benefit of parole.” Therein stands the grim reality of then-candidate Donald Trump’s proposition that there has to be “some form of punishment” for women who undergo abortions.

Or maybe the grim reality exists in Texas, where, following the state’s restrictive abortion bans, a 26-year-old woman was charged with murder after the police said she caused “the death of an individual by self-induced abortion.” That woman, Lizelle Herrera, was later released. But not before she spent days in prison on a $500,000 bond.

The Louisiana bill to characterize abortion as murder was reported out of the Committee on Criminal Justice favorably—with a vote of 7–2. But the legislation quickly caught the attention of the national press. Two days after the bill sailed through the committee, anti-abortion policy shops jumped in and condemned the language. The Louisiana Illuminator later reported that Republicans plan “to remove language from a high-profile bill that would allow prosecutors to charge pregnant patients who undergo abortions with murder.” But with Roe nearly extinguished, the anti-abortion policy wonks may not be able to put out all the fires. There may very soon be “some sort of punishment” for women who undergo abortions. And what once looked like just another Trump blunder may instead end up being a grisly part of his presidential legacy.