Over the past several days, there has been a subtle but significant shift in the U.S. approach to the war in Ukraine. No longer is the U.S. focused on simply ending the conflict. The goal now is to “weaken Russia.”

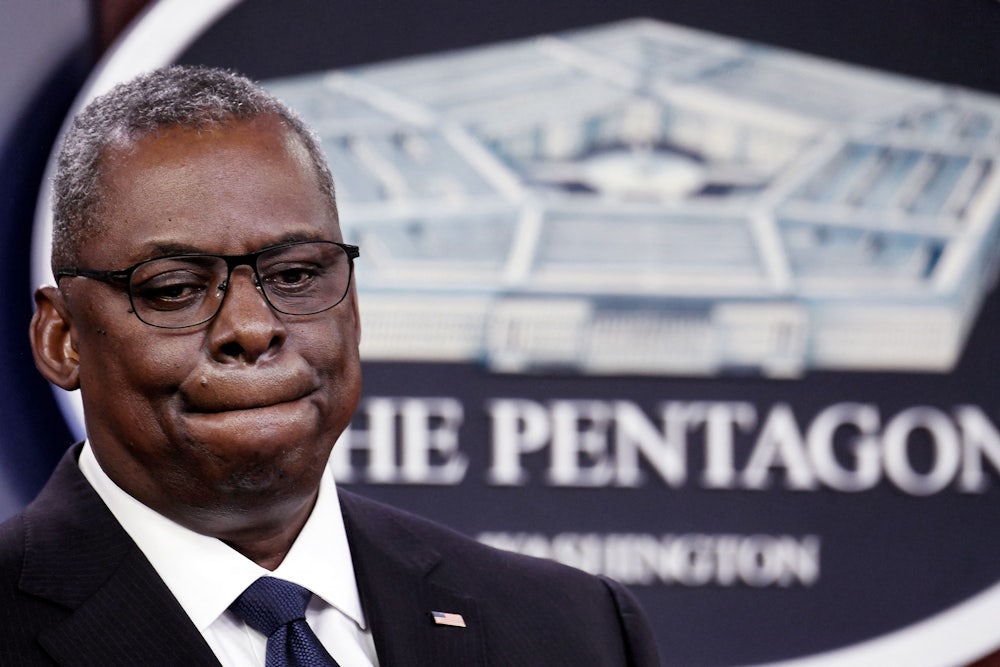

In his recent trip to Kyiv with Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin made this crystal clear. “We want to see Russia weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine,” said Austin.

The point was echoed by Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley, who said on CNN that the U.S. wants “a free and independent Ukraine,” and “that is going to involve a weakened Russia, a strengthened NATO.”

A spokesperson for the National Security Council went a step further, telling CNN, “We want Ukraine to win.”

But what does Ukraine “winning” and a “weakened Russia” look like? And, more important, is helping Ukraine “win” a realistic strategy in the best interests of U.S. national security?

On the surface, a Ukrainian victory in its war with Russia would mean forcing Russian troops off Ukrainian soil. That’s a laudable goal but one that hardly seems achievable, considering Russia’s military might and Vladimir Putin’s clear desire for a victory in Ukraine—to say nothing of the fact that Russia has controlled swathes of Ukrainian territory since 2014. Would it be enough for Russia to abandon the territory it has seized since the war began, or would Moscow have to withdraw its troops from Crimea and end support for insurgent forces in the Donbas region?

Perhaps winning means preventing Russia from prevailing—which would also have the practical effect of weakening Russia because it would ensure that the war drags on for months, even years longer.

But such a strategy brings with it potential dangers.

While before the war began the U.S. tried to prevent a Russian invasion—and after the war started tried to end it—the new strategy suggests a willingness to see the war prolonged.

Indeed, privately American officials are saying as much. Last week, The New York Times quoted anonymous American officials describing the rationale for quickly sending more weapons to Ukraine:

If Russia can push through in the east, Mr. Putin will be better positioned at home to sell his so-called ‘special military operation’ as a limited success.… He might then seek a cease-fire but would be emboldened to use the Donbas as leverage in any negotiations.… But if the Ukrainian military can stop Russia’s advance in the Donbas, officials say Mr. Putin will be faced with a stark choice: commit more combat power to a fight that could drag on for years or negotiate in earnest at peace talks.

The notion that Putin would take the latter course seems to run completely counter to what we’ve been hearing recently from the Kremlin.

As noted in a fascinating new report by two British scholars at the Royal United Services Institute, “Russia is now preparing, diplomatically, militarily, and economically, for a protracted conflict.” Indeed, when Russian military authorities recently announced a shift in strategy, away from seeking to capture Kyiv and focusing instead on the Donbas region of Eastern Ukraine, it was not matched by a de-escalation in Russian rhetoric. Instead, the exact opposite occurred: heightened, inflammatory language.

/ In honor of Earth Day, TNR’s climate coverage is free to registered users until April 29. Start reading now.

On April 18, for example, Vyacheslav Nikonov, deputy head of the State Duma, declared on Russian television that “this is a metaphysical clash between the forces of good and evil.… This is truly a holy war we’re waging and we must win.” As the analysts noted, the language coming from Russian leaders has become far more dire than the way the “special operation” in Ukraine had previously been described.

More ominously, Russian officials are also ramping up their attacks on NATO and the U.S.—and depicting Ukraine merely as a proxy for the West’s nefarious intentions vis-à-vis Moscow.

The Russians appear to be laying the groundwork for a larger and longer mobilization. This is not the language or domestic approach of a national leadership looking for a quick exit ramp.

But the longer the war drags on the more it will cost—both in terms of military resources expended and in increasing the economic damage inflicted by international sanctions. A military stalemate that drags on through the summer and fall (or perhaps longer) could have the effect of bleeding Russia dry.

All good, right?

Well, not so fast. The overriding concern of American officials since the war in Ukraine began (aside from trying to end it) has been to prevent it from escalating and somehow bringing the U.S. or NATO into the fight. That’s why American officials, early on, ruled out sending American troops to Ukraine, and it’s why they demurred on the idea of a no-fly zone over the country.

Such actions risked triggering a direct conflict between the West and Moscow.

Well, so too could a military stalemate that leaves Putin searching for a face-saving gambit. Every day that the war goes on, every day that U.S. military shipments are finding their way to Kyiv, and every day that the U.S. is sharing intelligence with Ukrainian forces, the potential for direct conflict between the U.S. and Russia increases. What if, for example, Russia tries to follow through militarily on its recent veiled threats against Ukraine’s neighbor Moldova? Or escalate the situation in Transnistria, a contested region along the Moldovan border where Russia has stationed “peacekeepers”?

While once the goal of American officials was to avoid at all costs such a situation, with calls for weakening Russia or a victory for Ukraine they are taking a very different and undoubtedly riskier approach. And the danger is not just military. The longer the war goes on, the more the global economy bears the brunt of the intensive sanctions regime on Russia and the inability of either Moscow or Kyiv to export its products. This situation will make it all the more difficult to keep sanctions on Russia in place.

Considering the actions of Russia to date, the U.S. position is hardly surprising. Weakening Putin—and preventing him from wreaking havoc in his near abroad in the future—is an eminently reasonable position to take.

But the ultimate goal here is to end the bloodletting in Ukraine. Period. And not just because it will save lives but because it will stop the potential for a dangerous escalation.

At this point, ending the war will not look like a “win” for either side. Both sides will only find their way out of the conflict if they can somehow declare victory—and that regrettably includes the unprovoked aggressor. The goal of a clear-cut Ukrainian win is not realistic—a fact that Kyiv seems to understand but its boosters in the West have yet to fully accept.

The Biden administration seemed to understand that point for the first few weeks of the conflict as it sought a diplomatic compromise. This latest shift in strategy is a worrying sign that U.S. goals in Ukraine are moving in a different and potentially more dangerous direction.