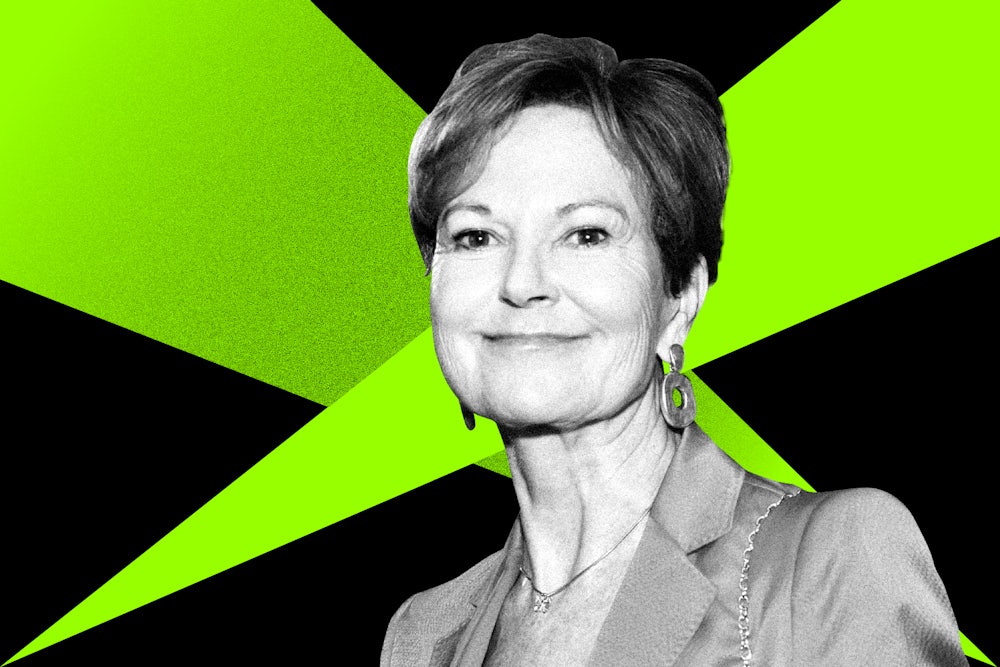

Kati Marton has seen much upheaval in her birthplace of Hungary. Her parents were acclaimed journalists who won a George Polk Award for their coverage of the 1956 Soviet invasion—shortly afterward, they were forced to flee to the United States. Marton herself became a foreign correspondent for ABC and NPR and has gone on to write nine books. Her latest, The Chancellor: The Remarkable Odyssey of Angela Merkel, released last year, has been translated into 18 languages.

This weekend’s elections in Hungary dashed the hopes of Marton and others that the authoritarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán could be defeated at the ballot box. The six opposition parties, left to right, got together behind a unity candidate, a conservative Catholic who supporters thought might be able to penetrate Orbán’s voting base. But in the end, Orbán won a fourth term handily. Marton notes that Orbán’s strategy relied less on his opponent and more on invoking fears around enemies like the European Union, George Soros, and Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskiy, who had criticized Orbán during the race as a puppet of Vladimir Putin.

Another reason for the big win: Orbán and his cronies now almost completely control the media. But their control is more subtle than Putin’s over the Russian media. “Journalists no longer get arrested,” Marton said, “they get driven out of business.” Throughout the entire presidential campaign, Marton said, the opposition candidate, Péter Márki-Zay, got five minutes of airtime on state TV.

Shifting the conversation to European geopolitics more broadly, Marton talked about Angela Merkel’s remarkable rise and tenure in power, and the influence the former German chancellor seemed to have over Putin while in office. Maybe, she conjectures, it’s worth sending Merkel on a mission to Moscow now to see if she can nudge him toward the negotiating table.