It was 1969, one year after the death of Martin Luther King Jr., and in Bolton, Mississippi, white Southerners’ ugly backlash to the gains of the civil rights movement was a powerful force. Three Black men had been elected to the Board of Aldermen, after succeeding in registering the small town’s significant population of Black voters with the help of federal registrars, as permitted by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The town’s white population revolted, and an unsuccessful lawsuit to prevent the three from taking office ultimately died in a federal court of appeals.

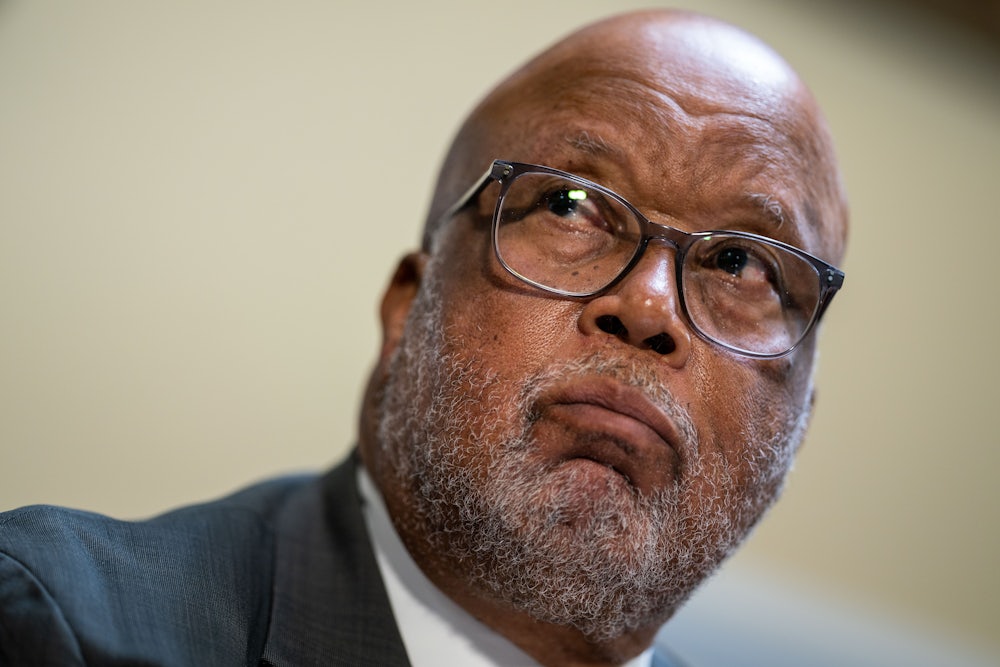

One of those men, 21-year-old Bennie Thompson, had run for office because he wanted change for the town’s Black residents: improved housing and infrastructure, fire and police protection, recreation for young people. “It was kind of an icebreaker,” Thompson, now a member of the U.S. House, told me more than five decades later. “The establishment in the community saw this as a threat to their way of life.” The city clerk had told him in the first meeting of the new council that he would not do anything the Black aldermen said. The system, and the people who had long defined it, did not want to change.

Thompson faced another failed lawsuit after he won the mayoral election for Bolton in 1973. When the Mississippi State Highway Patrol set up roadblocks to harass Black citizens during voter registration drives while he was in office, Thompson recalled to me, he took them to court. “It was always hard. But we always operated within the system,” Thompson said. “You didn’t have to stand on the corner and holler loud, you just understood you can have your day in this country in court. Just make sure that you do it the right way.”

Decades after overcoming challenges to his own elections, Thompson sits atop a panel dedicated to uncovering a conspiracy to overturn President Joe Biden’s electoral victory. Last July, he was tasked by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to lead a select committee to investigate the attempted insurrection and storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. The committee was approved almost entirely along party lines, and its members were chosen by Pelosi. Although two Republicans sit on the panel, they have largely been excommunicated from their own party, and Thompson has the unenviable task of ensuring the work of the committee is not seen as politically motivated.

Thompson’s chairmanship of the select committee is not just a capstone of the career of a respected congressman and chair of the Homeland Security Committee, but of his life’s work of subverting systems while still acting within them, using his relative power to methodically scrub the grout of racism and corruption from their halls.

Thompson’s supporters delineate a clear path from Thompson’s upbringing, education, and career as a Black man in Mississippi, a state riven by the domestic terrorism of white supremacists in the decades between Reconstruction and the civil rights movement. The highest number of lynchings in the country between 1882 and 1968 occurred in Mississippi, according to the NAACP.

“He clearly understands that when you have domestic terrorism that goes unaccounted for, you can be guaranteed that you will have more acts of domestic terrorism. That has been the experience across the South, but especially Mississippi,” said Derrick Johnson, the president and CEO of the NAACP and a mentee of Thompson. “And so in this moment, as he chairs the January 6 [committee], the importance of holding people accountable for the insurrectionist acts on our nation’s Capitol—if we don’t hold people accountable, he clearly understands it only opens the door for more acts of domestic terrorism.”

Thompson was born in Bolton in 1948, the son of a mechanic and a schoolteacher. His father died while Thompson was in high school, and friends stepped up to help raise him, instilling in the young Thompson a strong sense of community and sense of connection to the small hamlet of just a few hundred residents.

Some people are possessed with a preternatural sense of purpose, a seriousness that lends them an air of gravitas even at a young age. “You know when you are in college, and there are just some people that seem like grown-ups, more than the other students? Bennie was always like a grown-up,” said Oleta Fitzgerald, now the Southern regional director of Children’s Defense Fund, but once a classmate of Thompson’s at Tougaloo College.

In the late 1960s, Tougaloo, a private Black college on the outskirts of Jackson, Mississippi, had a population of particularly civic-minded students. Just a few years before Thompson and Fitzgerald attended Tougaloo, nine students held a sit-in at a public library in Jackson in an effort to integrate the facility, a protest that catalyzed a wave of civil rights demonstrations in the state. The school provided a safe space for Freedom Riders and hosted meetings led by Medgar Evers, the president of the Mississippi NAACP. Martin Luther King Jr. was among the luminaries in the civil rights movement who spoke at the college’s Woodworth Chapel.

Thompson thrived in this atmosphere, joining the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and volunteering for civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer’s ultimately unsuccessful congressional campaign. He recalled meeting such icons as King and John Lewis, who later served in Congress along with Thompson and remained a lifelong friend. “Tougaloo was probably that point in my life that convinced me to stay in Mississippi, to choose public service as a lifelong occupation, and just to try to make, in my own way, a difference in the lives of my state and my community,” Thompson said. (It was also where he met his wife of more than 50 years, London.)

The college provided him with the framework to understand the structural racism that underpinned life in Mississippi—why his side of town had no sidewalks or spaces for recreation, why his school’s textbooks were secondhand and out of date. “Tougaloo helped me make the connection of how that develops. But it also gave me the way forward of how you work toward institutional change in a community,” Thompson said.

After becoming mayor of Bolton, Thompson helped organize the Mississippi Conference of Black Mayors, which successfully lobbied for federal funds to aid the region. Thompson spent his time as mayor determined to improve infrastructure for the town’s Black residents: Streets were paved, housing renovated, and a new City Hall constructed. “The city halls are no longer places our black folks fear to come,” Thompson told The New York Times in a 1979 article. Major cities like Detroit and New York donated firetrucks and garbage trucks. The town reevaluated its real estate, revealing that many white residents had been undervaluing their property. A segregated pool was closed, and land was repurposed to build a new municipal building.

“If I have two roads, a paved road with potholes in a white neighborhood and an unpaved one in a black neighborhood, my priority is the unpaved road,” Thompson said in a 1985 profile written by Joe Klein for Esquire. “Equality doesn’t mean spending the same amount of money on blacks as whites. It means giving blacks the same quality of service as whites.”

After his election to the Hinds County Board of Supervisors in 1979, his statewide influence quickly grew. Thompson considered running for Congress in the 1980s, after a congressional district with a majority African American population was created, but ultimately decided against it. In 1986, Mike Espy became the first Black man elected to Congress from Mississippi since Reconstruction. (In the 1985 Esquire interview, Thompson said he didn’t think that he was the right “piece of equipment” for the job of congressman.)

When Espy was selected by President Bill Clinton to serve as secretary of agriculture in early 1993, Thompson ran in the special election to fill the vacant seat. Thompson defeated the Republican candidate for the seat in a runoff election, mobilizing the district’s Black voters. A New York Times article detailing Thompson’s victory said he was “regarded as far more confrontational” than Espy, noting that he “made no overtures to white voters.”

In Congress, Thompson focused much of his work on racial equity. He wrote the legislation creating the National Center for Minority Health and Health Care Disparities in 2000 and advocated for federal funds to be properly allocated after Hurricane Katrina ravaged the Gulf Coast, as well as calling for greater oversight and reform of federal agencies that managed the aftermath of the crisis. Thompson became chair of the Homeland Security Committee in 2007 and introduced legislation implementing the remaining recommendations provided by the 9/11 Commission.

Sixteen years before the insurrection, on January 6, 2005, Thompson voted against certifying the electoral victory of President George W. Bush, objecting to the election results in Ohio. “You know, I cast votes based on what the issues are at that time,” Thompson told CNN last July, explaining his vote against certifying Bush’s election. “But again, I didn’t tear up the place because I cast a vote.”

Congress is a venue in which attention-seekers thrive, instinctively turning to camera lights like plants tilt toward the sun. But, although he has had his fair share of big-name interviews, Thompson has maintained a relatively low profile. He is well-known among his colleagues, but not necessarily a nationally recognized figure. “He’s one of the few people in politics who has no ego. He’s all about getting the job done,” said Representative Ritchie Torres, the vice chair of the Homeland Security Committee.

Thompson’s unpretentious persona may have allowed him to largely escape the wrath of the committee’s critics. His congressional colleagues describe him as even-tempered and levelheaded, able to command respect without shouting for attention. “I call him a ‘quiet giant.’ He’s someone who can walk in the room without saying things, but he makes you feel secure and comfortable,” said Representative Joyce Beatty, the chair of the Congressional Black Caucus.

Representative John Katko, the ranking member of the Homeland Security Committee, said he and Thompson have a “terrific partnership,” stemming from an understanding of the bipartisan importance of the committee’s purview. “It’s a real joy working with him,” said Katko, who is retiring at the end of the year. “That’s one of the guys I’m really going to miss working with when I leave here.” (Katko, who was one of just 10 Republicans who voted to impeach former President Donald Trump after the events of January 6, was sure to clarify that his praise of Thompson pertained only to the Homeland Security Committee.)

Thompson is also widely praised by members of the select committee, who say that he has fostered a collaborative environment. “He’s very careful and inclusive as chairman. He makes sure that we have an opportunity to reach consensus,” said Representative Zoe Lofgren. She added that she wanted to “particularly credit” him for his decision to elevate GOP Representative Liz Cheney to the role of committee vice chair. For her part, Cheney called Thompson a “tremendous leader” in a statement to The New Republic. “Bennie combines the wisdom, judgment, patience, and good humor necessary to guide our committee at this historic moment,” she said. “I’m proud of our work together and honored to be his friend.”

Although Thompson can be seen giving interviews on cable news, he is not a fixture. “I don’t do a lot of talking,” Thompson told me, “because I like encouraging others to be engaged with whatever the process is.” That focus on collaboration has served him well for the select committee, which includes two other committee chairs among its high-profile members: Lofgren, the leader of the House Administration Committee, and Representative Adam Schiff, the chair of the House Intelligence Committee.

“It’s a committee of bosses,” Torres said, “a committee of the most powerful personalities in Congress. And the one person who can manage it, who is uniquely equipped to manage it, is Bennie Thompson.”

Over the past year, Thompson’s new committee has proceeded at a rapid clip, as members issue dozens of subpoenas, conduct depositions, review thousands of pages of documents, and gather additional evidence. The committee has also been entangled in multiple lawsuits attempting to block it from obtaining information. On Monday, a federal judge ruled that Trump’s former lawyer must turn over a trove of documents, also concluding in his decision that the former president “more likely than not” attempted to illegally obstruct the counting of electoral votes.

Developments affecting the committee’s work continue at a fast pace. Recent reporting by The Washington Post and CBS News revealed a gap in Trump’s phone logs on January 6, 2021, of seven hours and 37 minutes. The committee may also have to wade into controversial waters and call Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’s wife, Virginia, to testify, based on reports that she lobbied the White House chief of staff to pursue efforts to overturn the election. “Based on the evidence we have in our possession, I feel very confident with inviting her to the committee, and if she refuses, issuing a subpoena,” Thompson told reporters on Monday, after the committee voted to recommend that the full House hold former Trump aides Dan Scavino and Peter Navarro in contempt of Congress for refusing to respond to subpoenas.

The committee is also expected to hold more public hearings this year, after just one high-profile hearing with Capitol and Metropolitan Police officers last summer. This work is in preparation for compiling a comprehensive report offering the definitive account of what occurred and providing recommendations for what the Justice Department and Congress can do to prevent such an insurrection from happening again. Power always changes hands, and Republicans are widely expected to retake the House in the midterm elections. That gives committee members a ticking clock to complete their task.

Thompson’s chairmanship of the January 6 committee is a natural progression from his pre-Congress days as a student, politician, and activist, said Fitzgerald, his college friend. What occurred on January 6, and the “vitriol and the racism” of the modern era, were reminiscent to Fitzgerald of what she and Thompson experienced during the civil rights movement. “We have a saying down here ... ‘America, welcome to Mississippi.’ So a lot of what Bennie is dealing with, I’m sure like all of us, we were hopeful that we wouldn’t see again,” Fitzgerald said. “But he has one of the strongest spines of anybody in Washington, and he understands that this kind of stuff cannot be given air. That it has to be addressed head-on, or it can quickly take us back to where we were in Mississippi in the 1950s and 1960s.”

Representative Jamie Raskin, a member of the January 6 committee, also drew a line from Thompson’s experiences confronting racist institutions in the Deep South to his leadership of the committee. “This was a convergence of a mob riot with a white nationalist violent insurrection, and an inside political coup. And Bennie Thompson has life experience dealing with all of these things,” Raskin said. “He understands in a deeper way the dynamics of both normal and abnormal politics.”

For Thompson, one of the honors of his committee chairmanship is in showing that the son of man who never voted—who couldn’t vote in the apartheid state of Jim Crow Mississippi—can lead the investigation uncovering the truths of a dark day in U.S. history. Can rise within the system that initially and aggressively sought to exclude him.

“It can demonstrate to … young people,” Thompson said, “that somebody who was not born on the right side of town, somebody who didn’t go to the best schools, somebody who basically by all indications is lucky to be alive, that properly encouraged can make it.”