Even for those who had predicted and had tried to ready themselves for war, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24 came as a shock. The scale of the attack was shocking. The assault on Ukraine’s capital city of Kyiv was shocking. So too was the immediate brutality of the war, which from the beginning was not confined to purely military targets but was calculated to instill terror in the Ukrainian people. Overnight, Ukraine went from being a country that had normal civilian life in most places, despite the Russian intrusions of 2014, to a war zone in which everything and everyone was potentially in danger. The humanitarian catastrophe of this unfinished war is already immense, from the more than two million refugees it has created, to the loss of life, to the damage done to Ukraine’s infrastructure. The images of suffering on display in this war, augmented by social media, are devastating to all those who have access to accurate information on the war’s course.

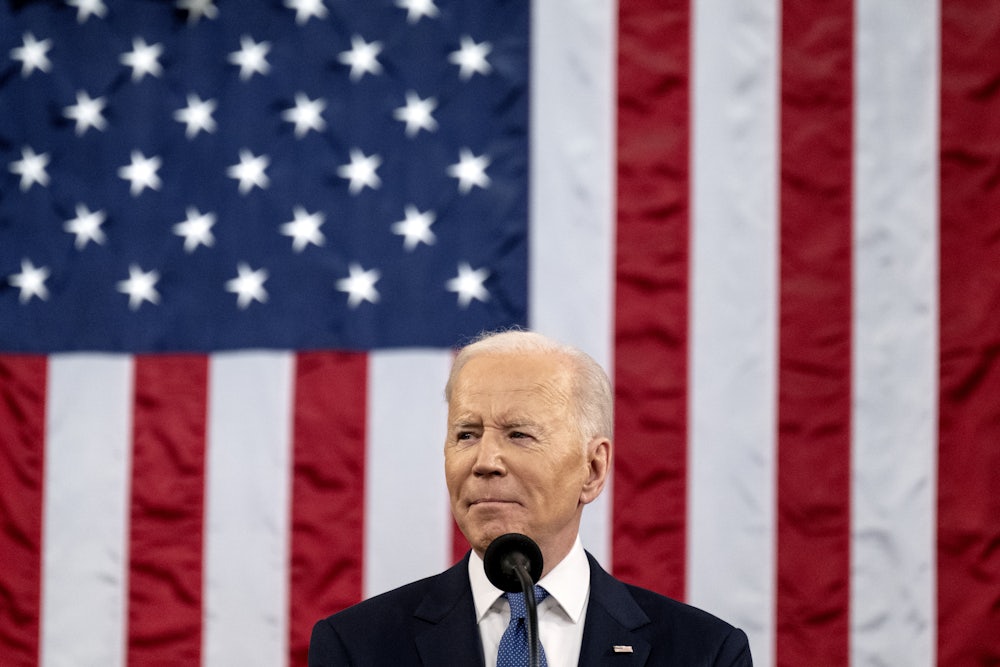

Because the war imposed itself so suddenly on the consciousness of those observing it in the United States, it has led to rapid changes of attitude and of policy. Ukraine was not a country that many Americans thought much about or knew much about before Russia’s invasion of 2022. Since the invasion, Ukrainian flags have proliferated in American cites and online. Grassroots efforts at fundraising to help the population of Ukraine have taken off. Cable news is covering the war nonstop. Policymakers have also swung into action. The U.S. has been rushing ammunition and weaponry to Ukraine. It has used its sizable bully pulpit to shame the shameless Vladimir Putin, and it has—in tandem with European and other allies—imposed sanctions of a kind that have never before been imposed on a country of Russia’s size and global stature. In no sense has the Biden administration been passive or slow in face of this terrible crisis.

Amid a news cycle of relentless speed and intensity, each day bringing thick headlines on the catastrophe of Putin’s war, it will be hard for the Biden administration to set long-term priorities. But at the moment there is no task more crucial. Even if Putin were to recall his troops tomorrow, Ukraine would be in a state of war-induced devastation and would require the world’s immediate attention.

Putin will, of course, press on with his war. Given his character and worldview, he cannot do otherwise, and in doing so he will alter not just the relationship between Russia and Ukraine but the very nature of Europe. This is a war that will recombine the DNA of global politics. Want it or not, a new world shall arrive. For this reason, the Biden administration should start developing three core priorities and hew to them carefully. Biden must support the government and people of Ukraine; degrade the Russian war machine, while seeking to contain the downward spiral in U.S.-Russian relations; and develop a new vision for this troubled region of Europe.

The U.S. has long had Ukraine as a partner. Since

2014, after the Maidan “Revolution of Dignity,” the U.S. forged a deep

connection with the government of Ukraine. In 2021, Ukraine was the third-largest recipient of U.S. aid. Washington has an extensive military

relationship with Ukraine, which has been, since February 24, the foundation

for its efforts to aid Ukraine at this moment of existential peril.

Volodymyr Zelenskiy has shown himself to be a charismatic and courageous wartime leader, and the Ukrainian soldiers and armed citizens have distinguished themselves against a formidable army that began the war with a sneak attack. The outcome of the war is impossible to predict, however, and the advantages held by the Russian military may still prove decisive on the battlefield, even if the war has, so far, gone badly for Moscow. Yet it makes perfect sense for the U.S. to provide Ukraine with ammunition and weapons—both for the material help such materiel provides the Ukrainian military and for the symbolism of the world’s preeminent military power backing Ukraine.

No less important than military aid will be humanitarian assistance. Ukraine’s population is almost 40 million. Its territory is vast. Before the war, it was among Europe’s poorest countries. The way in which Putin has been carrying out his war is intended to inflict great damage not just on the Ukrainian economy but on the rudiments of civilized life in Ukraine.

From U.S. immigration policy to considerations of postwar reconstruction, which are admittedly hard to formulate while the war is ongoing, this population will deserve all of the help that the U.S. can give it. In the coming months, Ukraine will experience crises of hunger and medical care. The population is already traumatized by a senseless and senselessly brutal war. This is a chance for the Biden administration and its European friends to demonstrate that the values they proclaim are the values they will be forthright in upholding—that the transatlantic alliance is neither about security alone nor about commerce alone.

The challenge of dealing with Russia offers fewer clear-cut options at the moment. It will require great discipline of thought, language, and action to master the task. Given the boldness of the sanctions, there are many different agendas to which they might be applied. No doubt many advocates of sanctions will be seduced by fantasies of regime change, for that on paper is the quick and simple solution—no Putin, no war, no problem.

But regime change has never been brought about by sanctions alone, and regime change as such is a policy with a long track record of failure for the U.S., from Afghanistan in 2001 to Iraq in 2003 to Libya in 2011. It is not that regimes cannot be changed. It is that they never end up changing in the way that policymakers in Washington wish. Putin’s paranoia is at this point impenetrable, and he will read malign intent into the most benign of policies and statements. Still, it is better not to signal any appetite for regime change in Russia, not least to the Russian population, which is not waiting for the American cavalry to save it from its widening tribulations.

Instead of regime change, sanctions should be tethered to a very specific purpose. This is to cut off outside support to Putin’s war machine. Putin is wrecking Ukraine with his army. Nothing guarantees that he will not wreck other countries with this same army inside or outside Europe. The sanctions will most likely not get Putin to think differently about war and peace. Over time, though, they can circumscribe the wealth and the technology transfer on which any military modernization relies.

It would be wise to recognize—as an opportunity cost of sanctions—that they tend to embitter the governments and the populations that are sanctioned. The stigma of sanctions can be more widespread than intended. To compensate, President Biden should use every chance he gets to address the Russian people and to tell them that the goal of the U.S. is not their immiseration. It is the cause of a more peaceful European and international order. Biden’s recent State of the Union address was a missed opportunity in this regard.

The greatest challenge for the Biden administration will be to continue arming Ukraine and to continue sanctioning Russia, without allowing an obviously conflictual relationship with Russia to spin out of control. The possibility of accident in a country at war and a country being helped along militarily by a bevy of outside powers is immense. The possibility of misinterpretation given the almost nonexistent diplomatic relationship between the U.S. and Russia is equally immense. The possibility that Putin’s hubris could push him in the way of the U.S. military is at the moment immense. The possibility that Putin’s perception of defeat in Ukraine could increase his appetite for risk is immense as well. Putin may not be capable of entering into a diplomatic relationship; he may not be well psychologically. That is beyond anyone’s control, including Putin’s perhaps, but Putin’s state of mind (whatever it is) does not eliminate the need to manage this crisis—to enhance the same deconfliction between the U.S. and Russian militaries that has been effective in Syria and to keep lines of communication open, though not necessarily open to public view.

The reimagining of Europe should start now. During the Second World War, the U.S. government began planning for postwar scenarios in 1942, not long after the U.S. entered the war and several years before the war ended. It put real resources behind the effort, gathering not just military brass but academics and experts to think about the possible directions Japanese and German politics might take. No doubt they made many false predictions and many errors of fact and of judgment. But without their analytical and planning work, the postwar occupations of Germany and Japan would surely have gone very differently—and not for the better. The State Department’s Office of Policy Planning, set up in 1947 by George Marshall, whose intellect did more than anyone’s to guide the U.S. war effort, had a mandate derived from World War II. This was to think ahead, to anticipate trends, and to align policy not only with the imperatives of the moment but with the imperatives (however imperfectly intuited) of the future.

The World War II analogy is helpful only to the extent that it demonstrates the value of thinking ahead. Russia’s war with Ukraine will not end as World War II did, which is to say it will not end with Russia’s unconditional surrender. Russia is unlikely to transition in the next few months or years into a peaceful, European-oriented democracy. It is unlikely to approach the war with Ukraine in the spirit of official shame that Germany did willingly and at the behest of the postwar occupying powers. Even in military defeat, for which Putin has set up his military by sending them into this criminal war, Russia is likely to remain committed to its core vision of central and Eastern Europe dominance and to do what it can to foster deferential or subservient governments on its enormous border with Europe. Russia is certain to remain a major nuclear power in perpetuity. This makes Russia both undefeatable and dangerous.

In this evolving situation, the situation generated by the war, the old recipes will not work. It will not be sufficient—and it will probably not be possible—to extend the NATO alliance to Ukraine after the war. Step one in rethinking Europe will concern Europe and the reconstruction of Ukraine’s western half, if Russia does indeed succeed in partitioning the country and in holding on to what it partitions—for that is Putin’s plan. It could be that the first step will be the reconstruction of the entire country if, by military misfortune or by a diplomatic settlement, Russia agrees to withdraw its troops from Ukrainian territory.

Step two, for Ukraine, will be to guarantee its security in

a way that will endure. Either this will demand a substantially greater

military commitment than the U.S. and the European members of the EU

and NATO were willing to give Ukraine before the war, so as to make a future

Russian invasion impossible. Or it will demand a diplomatic engagement with

Russia that will convince Russia to accept Ukraine’s independence and

sovereignty—no small task.

The hardest part of the puzzle, going forward, will be Russia itself. Moscow is waging an unwinnable war. Russia’s economy is nearing disaster. Putin has amassed war crimes on his own and on the part of the commanding officers who are following his orders. Because Russia cannot be defeated, it will not be in the position of postwar Germany after the war. It is probable that Russia will be chastened by the war, will be reduced by the war in many ways—but that it will also have the poison of anger and grievance in its politics, much like the Germany that lost World War I. Here the Biden administration should bear in mind the mood and tenor of Russian life and of the many millions of Russians who are not culpable for the war. They should figure in its outreach, in its messaging, in its speeches. There is no magic formula for undoing anger and grievance. There is merely the historical awareness, which U.S. policymakers had in abundance circa 1945, of where unchecked anger and grievance can lead.

All wars are tragic, and Putin’s war against Ukraine is especially so. It will wreak havoc on the global economy. It will compel the U.S. and Europe to direct money that could have gone to dealing with climate change or with public health crises or with inequality to military spending. It will bring regional and possibly global disorder in its wake, a ripple effect of further conflict that war always has the potential to cause. The war’s worst effects will be felt in the lives of Ukrainians, in their collective anguish. The best that can be done with war, apart from ending it, is by the alchemy of intelligent policy and intellectual boldness to transform its horrors into eventual opportunities. That was the story of World War II, the paradigmatic unjust war that unexpectedly left Germany pacifist in spirit and Western Europe newly capable of peace and integration. In real time, though, the war was only bloodshed. The opportunities could only be guessed at. These are, in the late winter of 2022, the kind of guesses that the Biden administration should be doing all it can to embrace, before the future arrives.