People are still quitting their jobs in droves, and the Pew Research Center* had the bright idea to ask them why. Their answers suggest that management needs the labor movement to revive itself at least as much as workers do.

Let me emphasize at the outset that a high quits rate is very good news. When many workers are quitting their jobs, that’s a sign of strong confidence that they can get a better job elsewhere. There can be unfortunate economic side effects to this, like inflation. But unless inflation settles in for a long stay, which seems doubtful, that’s a trivial story compared to the good news that workers feel they’ve acquired greater control over the direction of their lives. After nearly five decades of widening income inequality, you can’t have better economic news than that.

The Great Resignation is such a wonderful development that I’ve had some trouble believing it’s real. In June 2021, I called bullshit on the Great American Labor Shortage, and in July 2021 I said the temporary shortage was ending already. These judgments were wrong. I still think I was right that the number of Covid-19 cases—the most important economic indicator these past two years—was driving the Great Resignation. But like many people last summer, I was in too much of a hurry to believe that the Covid emergency was ending when it wasn’t. It looks like it’s finally ending now, but I could be wrong about that, too.

The data that the Bureau of Labor Statistics released Wednesday showed a quits rate in January 2022 of 2.8 percent, only slightly below the historic high of 3 percent that we saw in November and December 2021. The quits rate has been stuck at this very elevated rate since April 2021, when it hit 2.8 percent. (A normal rate is more like 2 percent.)

An important caveat is that these new data describe what was happening two months ago. Covid cases were still climbing nationally during the first half of January, and though they declined sharply after that, they were still higher at the end of January than they’d been for most of the pandemic. Cases are much, much lower now—as low as they were in July 2021—and they’re continuing to fall. That may mean the quits rate is lower now. In February, the number of jobs grew by an astonishing 678,000, which could portend a lower quits rate for February. Then again, in January the number of jobs grew by 481,000, which was also a lot. Yet the quits rate remained near its peak.

What’s certain is that the quits rate got stuck near record levels for 10 consecutive months. Even if you blame that, as I do, on Covid-19, the Great Resignation lasted longer than anybody, including me, would have predicted. Anthony Klotz, the Texas A&M psychologist who coined the term “Great Resignation,” believes its causes are psychological rather than economic, and in October I was inclined to agree. I still think psychology was a major factor. Klotz sees quitting as an expression of pent-up frustration with the pandemic combined with life reassessment brought on by “mortality cues.”

But after 10 months it’s time to ask a few economic questions. Which brings us to the survey Pew released Wednesday, in which workers were asked why they quit their jobs.

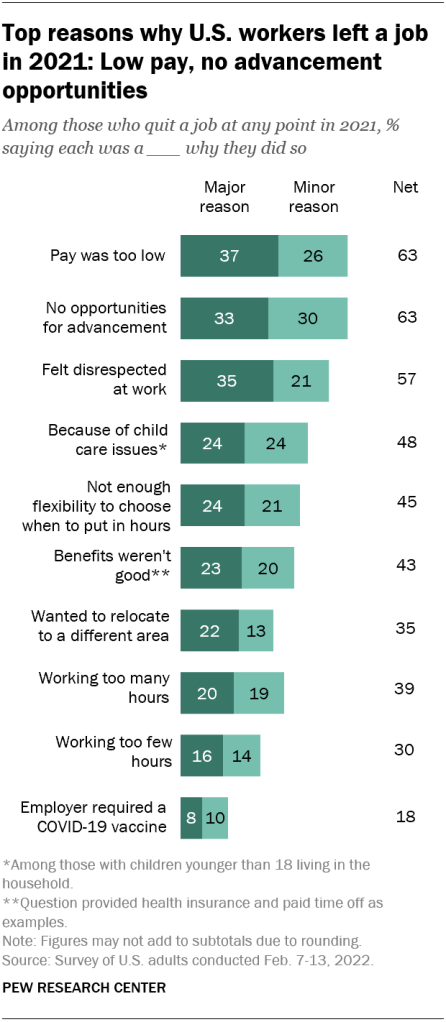

The best news here is that “Employer required a Covid-19 vaccine” came in dead last. Just 8 percent cited it as a “major reason” they quit, and 10 percent cited it as a “minor” one.” That’s a combined 18 percent, and I wouldn’t be surprised to learn half those people cited the vaccine just to register protest. The Great Resignation isn’t about employers requiring workers to get vaxxed.

The top three reasons people cited for quitting were “Pay was too low” (major reason, 37 percent; minor reason, 26 percent); “No opportunities for advancement” (major, 33 percent; minor, 30 percent); and “Felt disrespected at work” (major, 35 percent; minor, 21 percent). All three of these responses point to market failure.

If an employer is struggling with high turnover and he’s the rational player that economic theory presumes, then he’ll raise wages sufficiently that workers will want to stay. That isn’t happening, and after 10 months you have to ask yourself why not. Yes, wages are going up, but not sufficiently to keep the quits rate down: 56 percent of workers who quit last year and are now working for someone else say they’re making more money. The only rational actors in this transaction appear to be the workers who quit.

Or maybe not. Maybe the employer is behaving rationally. He gripes about high turnover, but he’d rather live with that than pay higher wages. That almost certainly describes the situation faced by restaurant and hotel workers. It’s also consistent with 63 percent of workers polled by Pew saying they saw no opportunities for advancement in their previous job.

Lower-tier jobs offer fewer opportunities for advancement than they did half a century ago because the workplace has fissured to segregate lower-wage workers in separate business entities like fast-food franchises and staffing agencies. People in lower-wage jobs don’t typically work for big corporations; more likely, they work for small organizations that keep wages down because their profit margins are wafer-thin and/or because they win subcontracts by being the low bidder. You can’t advance to a better-paying job, because you don’t just have a crap job—you have a crap job in a company where all the jobs are crap jobs.

You want to work your way up from the mailroom at Widget International? Tough luck. Widget International doesn’t employ mailroom workers—a subcontractor does. You feel the higher-ups at Widget International treat you with disrespect? That’s because they don’t think of you as part of their team. Because, actually, you aren’t part of their team.

These are big, structural problems that no individual worker is in much position to address except by quitting. No individual franchisee or staffing agency can do much to address them, either. The result, for those franchisees and staffing companies, is chaos. Worker dissatisfaction is their business model, and most cope with it the best they can. It’s an absolute mess. So if the labor market gets tight enough to get a better job, workers grab it, because, well, they’d be nuts not to.

The fissured workplace came about in an era when unions were declining in power, mostly in service industries that were seldom unionized to begin with. Big, thriving corporations were permitted to shear off a large portion of their workforce because there were no unions to stop them. Nothing much will be done to relieve this misery until unions become powerful enough to reshape the industries in which they reside. In the meantime, for a short while, workers have a tool for trading up. They can quit, and in a temporarily tight labor market, they can get something a bit better. It isn’t a sustainable model to reverse inequality, but for however long Covid makes it last, it’s a blessing.

* This piece originally misstated the name of the Pew Research Center as the Pew Charitable Trust.